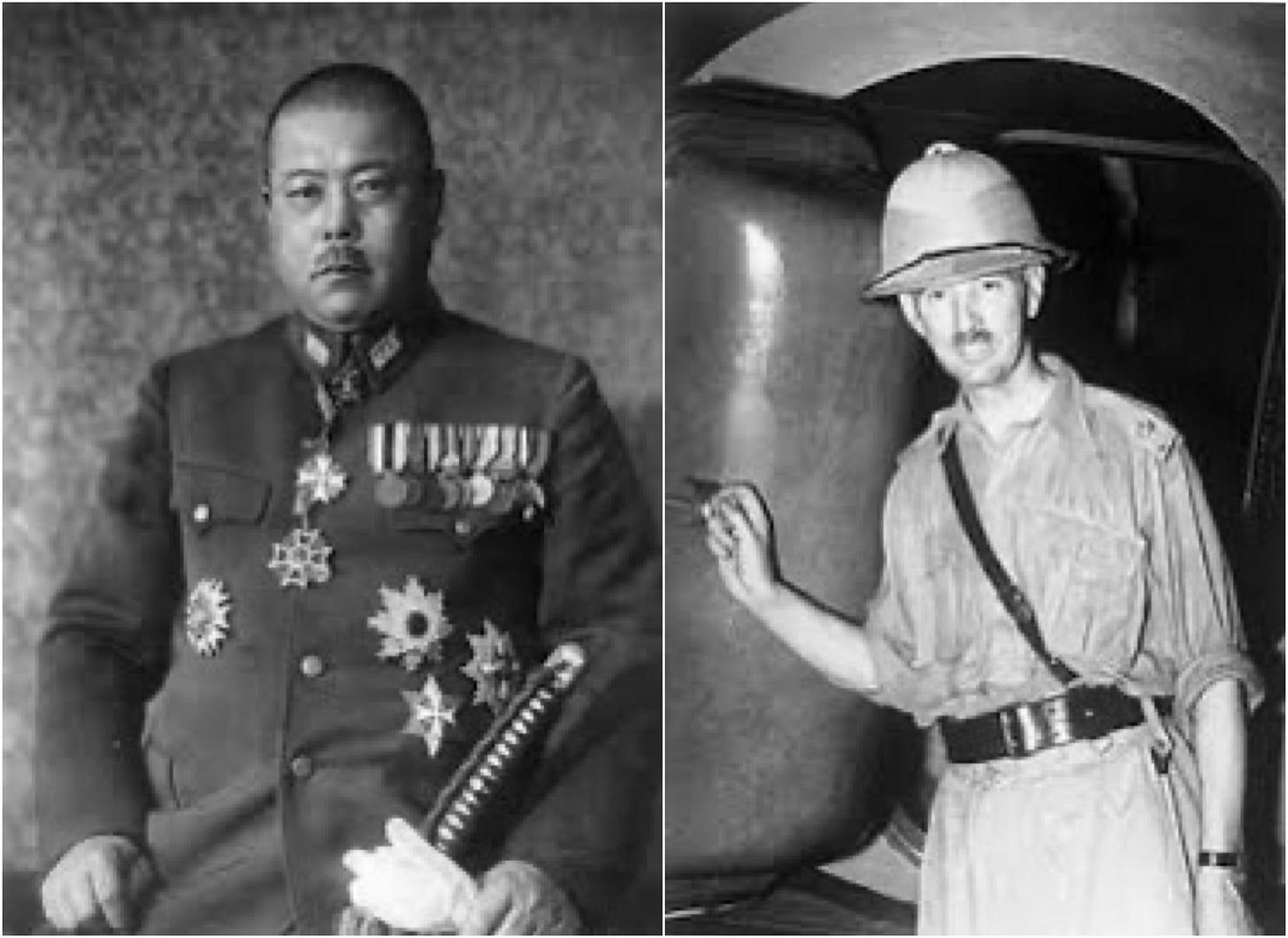

The campaign in Malaya which ended with the Japanese capture of Singapore on 15 February 1942 was a context amongst others between two commanders, Generals Yamashita and Percival. I’ll be taking a group to Malaysia and Singapore in March 2025 with The Cultural Experience and have been preparing an analysis of both men and the circumstances in which they found themselves in 1941. If you want to learn more, do have a look at my The Generals, published in 2008.

This first post is about Yamashita: I’ll follow it with one in Part II on Percival.

Yamashita

On late evening 7 December 1941 Lieutenant General Yamashita Tomoyuki (pronounced Ya-mash-ta), on the requisitioned cargo ship Ryujo Maru (‘Dragon and Castle’), prepared his invasion force – 26,000 troops in a 32-ship convoy (twenty transports, two cruisers and ten destroyers, together with five submarines) to disgorge at three points along the eastern Malay and Thai coastlines.

Yamashita accompanied his northernmost troops as they made their way ashore on to Thai territory at Singora, from where he launched an attack into British-held Malaya. A large man (14 stone and over 6-feet tall) he was a commander who led from the front.

We do not have the benefit from his pen of a ‘Victory into Defeat’ to put Yamashita’s side of the 1942 story. He was hanged by General Douglas MacArthur for war crimes committed by his troops in the Philippines during the final battles for the island in 1945. Nevertheless, the little we have to judge him by – the collapse of Malaya and the capitulation of Singapore in an astonishing seventy days in 1942 – would appear on its own merits to be evidence of a rare and remarkable genius.

The headlines that surrounded Yamashita’s feat propelled him into the 1940s Japanese equivalent of a media celebrity, with the label of ‘Tiger of Malaya and immediately established his reputation as one of Japan’s greatest generals of the ‘Great East Asian War’. Plaudits were received from Wehrmacht generals whom he had befriended in Germany during a six-month military mission to Europe earlier in 1941 and who had so proudly shown him the results of their own blitzkrieg in France.

It was in his own breathtaking ‘lightning war’ in Malaya and Singapore that the true extent of his generalship could be seen, a generalship of skill, thoughtfulness and careful preparation. Subordinates were told what to achieve, not how to achieve it. They were expected to succeed, because they had been trained and prepared to do what was asked of them. There was no expectation of failure. Determination, subtlety, imagination, flexibility, commitment and driving energy were military virtues prized above all else. Doctrinal orthodoxy, if it became an excuse for mediocrity or hesitation, was rejected outright.

In December 1940 he was appointed head of the Japanese military mission to Germany and Italy. There he had the opportunity to see at first hand the results of the extraordinary German blitzkrieg of 1940 into France and the Low Countries and to consider how this had been achieved. He was struck by the fact that otherwise well-equipped and well-defended countries had fallen like dominoes in the face of decisive, combined arms attack. He saw the immense psychological value of powerful movements of fast moving armoured columns, attacking with integral artillery and air support and paying scant attention to their flanks and rear. In a range of areas he realised that if Japan were to attempt to replicate any of this success, her armed forces would need to be better equipped and in places restructured.

Japan’s decision to go to war, and to do so by simultaneously attacking European and American imperial possessions across the Pacific Rim, was made in Tokyo on 16 September 1941. The naval attack on Pearl Harbour was to be accompanied by three amphibious assaults elsewhere in south-east Asia. The most important task was to capture Malaya and thereby to lay siege to Singapore.

Malaya and Singapore were the jewels in the imperial crown in Asia. Producing nearly forty per cent of the world’s rubber and nearly sixty per cent of the world’s tin, Malaya was a prize to surpass all others. As for ‘Fortress Singapore’, the Japanese knew it to be anything but. Pre-war intelligence had shown clearly that this phrase was mere propaganda. Time would tell that the only people to have been deceived were those who continued unthinkingly to use the phrase as if it were real. Propaganda merged effortlessly into reality in the minds of those who wanted to believe that Singapore would always be safe.

The other two objectives were the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies.

Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo had begun planning for the invasion of Malaya at least a year before. Tokyo was supported by HQ 5 Army in Saigon, and by the establishment of a small specialist operational investigation unit in Formosa. This unit was responsible for collecting and analysing all the information necessary to prepare 25 Army to fight a tropical warfare campaign. Its remit was comprehensive, being tasked with advising on everything from ‘the organization of Army corps, equipment, campaign direction, management and treatment of weapons, sanitation, supply, administration of occupied territory, and military strategy, tactics and geography.’

The cornerstone of the plan was to land an invasion force unmolested in neutral Thailand from where it could make a rapid advance down the long thin spine of the Malayan Peninsula, attacking Singapore through its weakly guarded back door. The ambition was not to confront the British where they were strongest – the seaward defences of Singapore Island, bristling with anti-ship artillery – but where they had no defences at all, across the Straits of Johore.

Yamashita inherited these plans. He was given four divisions – a force totalling some 60,000 men, comprising 5, 18, 56 and 2 (Imperial Guard) Divisions. It was estimated it would take one hundred days to subdue the Malayan Peninsula and capture Singapore.

One of Yamashita’s first actions was to reduce the size of the forces he wanted to deploy. Instead of using four divisions, he stood 56 Division down. It would later be used in Burma. Three divisions, he believed, would suffice, as a fourth would overload his logistic capacity. His plan was to use 5 Division and 2 Imperial Guards Division to capture Malaya, concentrating both divisions in an advance along the main arterial route that led south towards Singapore on the west coast. He did not have enough resources to attack on more than a single front. A single front, nevertheless, would allow him to concentrate the combat power of his two divisions. When Singapore had been reached, he would then bring in the fresh 18 Division, until then remaining in Indochina, in order to be able to assault the island fortress with a full three divisions.

By the end of November Yamashita had moved his headquarters to Hainan Island, off the coast of China, in final preparation for the opening phases of the war. The operation with which he had been entrusted entailed massive risks. Yamashita would have to land his army at Patani and Singora on neutral territory in Thailand, just when the north-east monsoon was about to break. Because of the monsoon, December 8 was deemed to be the last safe moment for a landing. Even this date, with the anticipated swell, made the operation difficult. He then had to secure his landing areas and protect them from British counterattack by both air and land.

For this reason it was critical that the airfields in Kota Bahru and Alor Star be captured quickly, which necessitated a landing at Kota Bahru in north-eastern Malaya, even though it was known to be well defended. He had then to launch an offensive into Malaya, an attack he knew would be on the slenderest of logistical margins and against an enemy that understood the ground and was known to be superior in numbers.

It was clear to him that the success of the landings relied entirely upon the level of cooperation he could secure from the Navy. He quickly established a rapport with both Naval and Air commanders.

The relationship between all services was one of remarkable harmony throughout the campaign.

Yamashita had no role in constructing the strategic plan for the invasion of Malaya. What Yamashita brought, nevertheless, was both clear interpretation and successful implementation. However, when Singapore was reached, the plan and its execution for the attack on the island city was entirely Yamashita’s responsibility.

The first issue for him was to decide whether to strike into northern Malaya quickly and deeply after the landings, forfeiting the opportunity to establish a firm base in Thailand, in order to make the most of any initial British disarray? Or was it first to build up a strong defensive base in Thailand, from where he could meet and destroy any British counterattack? Both entailed risk. If he launched his offensive quickly it would not be as thoroughly prepared as it could be and might come unstuck at the hands of a vigorous British defence. However, if he delayed, he would lose the element of surprise, allow the British to regather their startled wits, substantially enhance their defences, and launch potentially devastating air attacks against the Japanese beachheads.

Yamashita chose to strike deep and fast at the earliest possible opportunity. It was clear to him that the first thing he had to do was to overwhelm his enemy, and he decided to do this by establishing and maintaining a tempo on the battlefield that would never allow the British to recover the initiative. This ‘driving charge’ (Kirimomi Sakusen) was to be the overriding principle of the advance: constant and overwhelming pressure on a narrow front with the enemy allowed no opportunity to rest. Yamashita had several reasons for believing that a Kirimomi Sakusen was the best tactic to employ.

First, his intelligence had told him that the bulk of the British Army in Malaya was inferior in training and morale to his own troops. He was particularly dismissive of the fighting prowess of the Indian troops who comprised a significant proportion of the British forces in Malaya. As it turned out, although the Japanese seriously underestimated British strength in Malaya, neither numbers nor race ultimately determined the battle. What mattered was the boldness with which these troops were used, and the capacity for boldness was determined by a range of factors in which experience, leadership, training and morale were central. Thorough intelligence had provided a detailed picture of the terrain, obstacles and primary enemy dispositions.

Second, his forces were experienced, hardy and well-prepared. The Japanese soldier was an aggressive fighter who, whilst not always good at demonstrating imagination, always fought with a single-minded determination to succeed that repeatedly shamed his less persistent opponents. In the brief time available 25 Army had trained hard on Hainan Island, absorbing the myriad of lessons picked up by the special unit on Formosa.

Much has been made of the fact that the Japanese were exquisite jungle warriors, and that it was the lack of comparable jungle training that stymied the British Empire troops in the country. There is only fragmentary truth in this idea. Familiarity with the jungle would have benefited British, Indian and Australian troops immensely, but the truth is that Japanese troops were hardly better equipped or trained to deal with the difficulties of jungle warfare than their opponents. It was not jungle warfare experience that made the difference, but leadership and training. Japanese soldiers were confident in themselves, and their leaders, and it was this confidence that allowed them to undertake tasks at which the more conservatively minded British, Indians and Australians baulked.

The war for Malaya was thus one of speed and mobility. For Yamashita’s Kirimomi Sakusen to succeed he needed to outflank British road blocks and to maintain the tempo of his advance. It was in this struggle that the Japanese ability to move off-road, and onto jungle tracks for short periods of time to insert ambush parties behind British blocks and so to undermine the British defensive plans and to disrupt their lines of communication, creating an atmosphere of confusion and uncertainty, that dramatically increased the combat value of Yamashita’s numerically inferior troops. The Japanese rarely fought in the jungle but used it extensively as a means to outwit their enemy (who were, on the whole, scared of it), to multiply their own strength, and to undermine the natural advantages enjoyed by their opponents.

Third, his troops were used to operating together, with other arms and services, to a degree that was unheard of in the British services. The planning and the conduct of operations were jointly conceived and executed. Yamashita and the commander of the 3rd Air Group (which remained under the direct command of HQ Southern Army in Indochina, and not HQ 25 Army, and which was responsible for supporting 15 Army’s operations in Burma and 16 Army’s in Sumatra as well as Yamashita’s in Malaya), Lieutenant General Sugawara, respected each other and worked well together.

Air and land operations were regarded by the joint army-air staff to be inseparable. The Japanese also had far more aircraft, a total of some 612 at the outset in four ‘Air Brigades’, than the British, a fact that gave Yamashita battlefield air superiority and allowed him to cow the civilian population of Singapore, as well as to demoralise the British Empire troops who saw their own feeble air force shot from the sky.

More important than numbers, however, was the fact that in terms of doctrine and leadership the 3rd Air Group rapidly denied the British access to the skies, and in so doing enabled Yamashita to enjoy virtually unrestricted movement on the ground. Sugawara regarded it as his task to clear the British from the air altogether, in a policy described as ‘aerial exterminating action’ to allow Yamashita the freedom to operate, rather than merely as a supporting appendage to ground operations. This doctrine constituted the destruction of enemy air assets either in the air or on their airfields at the earliest point in an operation, entailing a devastating pre-emptive strike against the enemy’s ability in turn to strike back. It was a revolutionary approach to the use of air power in war, moved the use of aircraft far beyond their traditional task of delivering close support to ground forces and brought with it catastrophic results for Malaya’s tiny and out-dated air force and consequently for Percival’s land forces.

Finally, the troops were intensely motivated. The war was widely perceived as a new dawn for Japan. There was a very real sense, sustained over many years by effective militarist propaganda, that the invasion forces were the divine instruments for securing Japan’s destiny. The spiritual purpose and motivation for the troops was overwhelming.

Throughout the entire campaign he was heavily outnumbered. He landed in Thailand on 8 December with 26,000 men (of whom 17,230 were combat troops) from the two regiments of 5 Division (making the main landings at Singora and Patani) and 56 Infantry Regiment of 18 Division, known as Takumi Force, which landed at Kota Bharu. He was reinforced within days by 2 Imperial Guards Division (13,000 men) travelling overland from Indochina through Thailand, which took his total strength in Malaya to 39,000. By the time he had reached Singapore Island he had suffered 4,565 casualties, which reduced his strength to some 34,000. However, he was then reinforced by 13,000 troops of Mutaguchi’s 18 Division, which landed at Singora on 23 January, a month after the initial landings, for the purpose of assaulting Singapore. He also had logistical and support troops that raised the number of his Army in Malaya (as opposed to remaining in Indochina) to some 60,000. But of these, a mere 30,000 were combat effective troops, available for the assault on Singapore. Yamashita had by this stage a mere eighteen tanks remaining from a starting number of eighty.

Together with these infantry forces he had also 132 guns of varying calibres, forty armoured cars, sixty-eight anti-aircraft guns and three regiments of engineers, together with three companies of bridging troops and three companies of river-crossing troops. His logistic support units included four telegraph and telephone companies, eight wireless platoons and two regiments of railway troops. Where he did possess a numerical advantage over the British was in aircraft. Sugawara’s 3rd Air Division boasted 459 aircraft, and the Navy provided a further 158.

The Japanese were able to confirm the number of British, Indian and Australian defenders through the numbers they took prisoner. These totalled 109,000, including 55,000 Indians, and clearly excluded the many thousands able to escape from Singapore in the dying days of the campaign. Percival always believed that he was faced by overwhelming odds – at least 150,000 men and 300 tanks. Had this been the case, the loss of Malaya and Singapore would have been at least understandable. The fact that Yamashita landed in Thailand and Malaya with one and a half weak divisions comprising a mere 17,230 combat troops and attacked Singapore with a total strength of no more than 30,000 combat troops makes the enormity of his achievement even the more remarkable.

While the two landings at Singora and Patani in Thailand were virtually casualty-free that at Kota Bharu in Kelantan provided an indication of the course the campaign may have taken if the resistance the Japanese encountered here had been more widely replicated. Three Japanese transport ships began disgorging 5,300 assault troops at midnight on 8 December, but from the outset British resistance was fierce. One of the ships, the Awagisan Maru, was struck by air attack as dawn broke, and caught fire.

The Kota Bharu landings cost Yamashita 858 casualties, although the plunder was considerable: 27 field guns, 73 machine-guns, 7 planes, 157 vehicles and 33 railway trucks. But it was the airfields that presented the greatest prize, that at Tanah Merah being captured on 13 December and Kuala Kulai six days later, as they prevented a British counterattack against his landing beaches. Yamashita recognised that control of the air was a product of the speed with which devastating offensive action could be launched. The faster he acted, the more rapidly would the British air effort be destroyed, and the faster, therefore, could his ground forces deploy.

From Thailand, quickly gathering together a small force of infantry, tanks and combat engineers, in requisitioned Thai transport, Yamashita pushed against the British defences along the Thai-Malay frontier. To his immense surprise, the British defences broke with ease. British plans to enter Thailand to deny key routes into Malaya to the Japanese were thwarted by indecision and Japanese speed, both on land and in the air, as well as in thought and action. 11 Indian Division was caught while trying ineffectually to advance to secure forward positions inside Thailand, but it had also neglected to prepare effective defensive positions upon which it could, if necessary, fall back. A Japanese vanguard of two hundred men under Lieutenant Colonel Saeki advanced aggressively along the jungle-lined road in the dark, wading through streams where the British had demolished the bridges.

The first encounter between Saeki’s men and men of 11 Division provided a disastrous foretaste for the British of how the campaign would develop. Crossing the border on the night of 9 December, the Japanese were surprised to find that the road itself was not blocked. For several miles no enemy were encountered, although the British kept the road under a relatively ineffectual artillery fire. Eventually a small group of enemy soldiers were encountered. Japanese accounts talk of a slaughter taking place, with many running away and failing to fight.

The inability or unwillingness of the British to resist strongly astonished the Japanese. They were even more amazed to discover the huge quantities of supplies, including fuel, food and ammunition that fell into their hands, which were immediately dubbed ‘Chāchiru kyūyō’ – ‘Churchill rations’. ‘We now understood the fighting capacity of the enemy’ wrote one. ‘The only thing we had to fear were the quantity of munitions he had and the thoroughness of his demolitions.’

Jitra

By the night of 11 December the weak and entirely speculative Japanese vanguard, still amounting to little more than two battalions, had fallen with unexpected speed upon Jitra. In the heavy monsoon rain, with trenches flooded, uncertain reports arriving from the forward reconnaissance screen, and having suffered days of ‘order, counter-order and disorder’, the cohesion of 11 Division had been dangerously weakened. Late in the afternoon, cloaked by a tropical downpour and by the noise of British artillery, ten of Saeki’s medium tanks crossed a bridge that had been demolished by the British but hurriedly repaired by Japanese engineers, and drove headlong into the British positions. But amazingly, it was not defended. Driving quickly along the road the Japanese came across ten 25-pounders, with their crews sheltering from the rain under the rubber trees. The Japanese tanks immediately engaged and destroyed the British armoured cars and guns, and infantry swarmed into the rubber plantation to attack the resting British troops, who had been, in their wet misery, entirely surprised.

This battle was the first decisive Japanese success in Malaya. 11 Indian Division was shattered, the northern airfields lost, and a pattern of defeat and withdrawal begun that was only to end at the gates of Singapore fifty-five days later.

Every possible means was used to maintain the momentum of the advance. Without waiting for orders his vanguard – comprising infantry, armour, engineers and close-air support all working in the closest unison – fought forward and aggressively without any thought for their rear. Their task was to push hard, ignoring their supply lines, whilst relying on captured supplies. Although their maps were small-scale and poor, Japanese use of ground once the enemy had been encountered was good, going off-road through the jungle to outflank and cut off the British positions.

No time was wasted. Forces were formed, re-formed and combined together flexibly to meet the needs of the hour. Whatever means at hand were seized to make the next objective. Japanese small-unit and regimental leadership was very good, and infantry initiative was much prized. Units leap-frogged over each other as lead elements became tired, to ensure an unremitting tempo. Units were ordered to drive forward regardless of all other circumstances, and to ignore firing from behind.

The defenders, exhausted and often in disarray, were forced to attempt to retire increasingly long distances to give themselves the opportunity to construct defensive positions out of contact with the enemy. Rarely were they given the chance. What was left of 11 Indian Division struggled back on 14 December from Jitra to Gurun, exhausted, to find not only the Japanese hard on their heels, but fixed defences and road blocks almost non-existent. Yamashita’s tanks, coordinated with fighter aircraft in the ground-attack role, gave the tired troops no let-up, with the result that within 24 hours 11 Division was forced to order yet another withdrawal, to the Muda River.

The Japanese proved more able to withstand the rigours of prolonged campaigning in a hostile environment in 1941 and 1942 than their opponents, with limited opportunities for rest and re-supply. They required less food, shelter, or transport, although they made the most of what they captured. They needed fewer instructions and relied to a far greater extent on the initiative of small unit (platoon and company) leaders. They were unimpeded by rain, swamp, rivers or jungle, and suffered less from the heat and tropical disease. They made the most of opportunities to seize the tactical advantage over slower moving adversaries and they improvised well. They were determined, brave and willing to die for their emperor. Their training was tough and realistic, and prepared them well for the stress of combat. It extended to combined operations with other arms: infantry, for example, trained with armour and engineers, and practised coordinating attacks with mortars and artillery. Unlike the British in 1941 and 1942, they also showed special prowess in air-to-ground co-ordination.

The key to Japanese mobility was the bicycle. In both 5 and 18 Division all officers and men not allocated to motorised transport, which tended to be the preserve of heavy weapons and ammunition, were issued with them. In each division there were roughly five hundred motor vehicles and six thousand bicycles, although in Malaya, of course, the number of vehicles was swollen by the capture of British transport.

What Yamashita sought to do was to maximise the psychological advantage of the frontal assault by adding to it that of an unnerving threat from the flank or rear. General Slim was later to describe these tactics in Defeat into Victory.

Their standard action was, while holding us in front, to send a mobile force, mainly infantry, on a wide turning movement round our flank through the jungle to come in on our line of communications. Here, on the single road, up which all our supplies, ammunition, and reinforcements must come, they would establish a ‘roadblock’, sometimes with a battalion, sometimes with a regiment. We had few if any reserves in depth – all our troops were in the front line – and we had, therefore, when this happened, to turn about forces from the forward positions to clear the roadblock. At this moment the enemy increased his pressure on our weakened front until it crumbled.

The epitome of generalship to Yamashita, echoing Sun Tzu, was the defeat of the enemy with the minimum of bloodshed. To him, excessive slaughter denoted a lack of sophistication or subtlety in generalship.

Kampar

The Japanese were held up for six days along the Kampar River, south of Ipoh, by spirited British defences (comprising the remnants of 6 and 15 Indian Brigades, an artillery Field Regiment and a battery of anti-tank guns). Despite initially successful tank attacks against infantry, Japanese frontal assaults failed to break through. One of the reasons for this was that the Japanese used their artillery poorly throughout the campaign, placing them individually with infantry units rather than using them together, as did the British, to fire en masse.

To solve the problem Yamashita slipped a regimental (i.e. brigade) group with one and a half infantry battalions, a section of mountain guns and a section of engineers forward by sea, cutting off the defenders from the rear. Efforts were also made to infiltrate troops around the defences, through jungle the British regarded to be impenetrable. The Ando Regiment, after struggling through difficult country for three days and three nights, broke out behind the British positions on 1/2 January 1942. The operation was one of extreme physical discomfort and exertion. The hardiness of the individual Japanese soldier and his willingness to suffer all manner of deprivations in the course of achieving his objective was a testament to the rigorousness of the Japanese training regime and their martial fervour.

Slim River

This tactic worked brilliantly. The Kampar defenders were so unsettled that a full withdrawal was in progress on 2 January 1942, the Japanese following on hard against the British backstop at the Slim River. This defensive position stretched over some twelve miles and contained two brigades positioned in depth along the length of the main road leading south in the direction of Kuala Lumpur. But British commanders, even in otherwise well-trained regular battalions, continued to make basic tactical errors: the need to cut the road, block the approach to tanks and then cover the block with artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, as well as to deploy artillery in the anti-tank role, had not yet been fully grasped.

Yamashita’s vanguard began probing these positions on 5 January. Late on the following day, the Ando Regiment, led by tanks driving furiously down a single road, succeeded brilliantly and comprehensively to dislocate the weary defenders, scattering them willy-nilly. The Commanding Officer of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, one of the most proficient British fighting units in Malaya, described the Japanese tactic as ‘filleting’, the backbone of the road being peeled back and removed from the infantry positioned on either side. With the road gone, and Japanese tanks clattering south, dispensing machine-gun fire liberally on either side, followed up by truck or bicycle-borne Japanese infantry, it was remarkably easy for inexperienced, poorly briefed or disorientated soldiers to lose heart, and to seep back through the jungle.

While often fighting courageously and determinedly against frontal assault, and on occasions causing serious damage and delay to Yamashita’s advance, the British (and Indians and Australians for that matter), were too easily undone by speculative penetrations to their rear, often by relatively weak forces. The casual insouciance of the Japanese in not following or obeying European norms of military behaviour (such as their use of the bicycle to increase their speed of movement, their refusal to be worried about their rapidly elongating lines of communication, the risks they took with their fast and furious ‘filleting’ attacks and their willingness to follow up and strike hard without waiting to consolidate), surprised their more conservatively-minded opponents who were often apt to mill around in confusion when the accepted patterns and timetables of military engagements were overturned.

By 9 a.m. on the morning of 7 January the Japanese had dispersed the defenders of Slim River, young Japanese officers aggressively pushing their tanks hard for long distances, and with little heed to their own security or lines of communication. By now, all Japanese combat commanders knew the enormous psychological impact they could achieve by shock action. The British and Indian units, on the back foot for nearly a month, were exhausted. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, for example, had lost a quarter of its strength, as had the 5/2nd Punjabis. Because of this overwhelming fatigue the commander of 28 Brigade insisted on his men resting on the night of 6 January before they took up their new defensive positions. It proved a disastrous error. The next morning the whole of 2/1st Gurkha Rifles, marching three miles to their new positions were caught by the advancing Japanese and the battalion destroyed. Those unwounded scattered into the rubber estates in a desperate bid to escape. The Japanese advanced at a pace that shocked the British. In a single day at Slim River Yamashita destroyed the remainder of 11 Indian Division and captured vast quantities of stores. Of the 576 Argylls available at the start of the battle only ninety-four survived. Seventy-five were killed in action and a further forty were killed as the Japanese ‘mopped up’ in the ensuing days. Forty died in the jungle attempting to avoid capture, by drowning, disease and succumbing to wounds. About thirty managed to escape by boat to Sumatra, and 300 were captured in the jungle, many after days and weeks on the run.

At the same time Yamashita had initiated raids from the sea on the west coast using a flotilla of about forty small boats, some of which had been carried overland from the east coast to land troops behind the British defences, sowing confusion and disorder. These raids (and the fear of them) achieved results far outweighing their size, including a panicked withdrawal of British forces from Kuala Lumpur on 11 January. Yamashita regarded the psychological advantage of these ‘little ships’ to be the decisive tactic in the campaign and the single greatest factor that beat the British in Malaya.

Yamashita’s tactics were framed by a rigorous and clear-headed rationalism that emphasised the science of war – integrated command, coordinated infantry, tanks, engineers and air power, intelligent use of surprise and deception to secure a psychological advantage of the enemy – over the banzai! charge and the hand-to-hand (or sword-to-sword) struggle of two individual warriors of a previous and perhaps mythologized past. Yamashita’s primary target was the will of the enemy, particularly that of the civilian population and the easily disheartened Indian recruits. Considerable effort was placed on propaganda, using radio and leaflets, to complement the terror tactics of aerial bombardment of the civilian centres of Penang, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. Within a day of the capture of Penang following the terror-bombing of its civilian population, the Japanese were broadcasting: ‘Hello, Singapore, this is Penang calling; how do you like our bombings?’ Likewise, Indian soldiers were counselled to disobey their colonial overlords and submit peacefully to their fellow-Asians in what was promised to be a new, post-colonial, Asian nirvana.

Despite the imperatives of his Kirimomi Sakusen, Yamashita worried about his increasingly stretched lines of communication. Once Singapore had been reached, these ran by road and rail 680 miles back to Singora. Through this route ran all of 25 Army’s supplies and reinforcements, and back along it flowed the casualties of battle. Troops repairing and running the line of communication, across 250 bridges, many hastily repaired during the battle, worked to exhaustion to keep the supply lines open. A whole division was assembled, for instance on one occasion, to repair the railway. This took a week, working day and night, which otherwise would have taken three. The risk was not that the British might interdict them – as Yamashita pushed his forces down into Malaya, the expectation of dangerous British counterattacks receded – but that they would break under the strain.

Singapore

With Malaya fallen, Yamashita was now faced with the daunting prospect of attacking and capturing the great Singapore fortress, the fabled bastion of British power and prestige in Asia. Yamashita decided to use all three divisions to assault across the Strait of Johore, the main attack coming from the north west with two divisions (5 and 18), with the Imperial Guards undertaking a diversionary attack to the east. The Guards were to capture Palau Ubin Island on 7 February and 5 and 18 Divisions would cross the Straits of Johore the following night. Reconnaissance and staff work for the crossing was completed by 4 February.

By now, however, Yamashita’s risks had multiplied alarmingly. His supplies – fuel, ammunition and rations – were now very low. In fact, he was relying exclusively on captured British stocks of fuel, he was down to four days’ worth of rations and his artillery ammunition was limited to 440 rounds for each remaining gun. The line of communication back to Singora was proving difficult to manage, he had somehow to transport two divisions across the Straits of Johore, a formidable water obstacle, and after nearly sixty days of continuous operations his troops were exhausted.

The dire lack of ammunition, fuel and rations led his chief supply officer to plead with Yamashita for a period of consolidation to allow his resources to build back up. Even the ‘Churchill’ supplies had been exhausted. Yamashita, however, resisted such pleas. He knew that success could only be secured if he continued the same relentless momentum that had propelled him through Malaya. If he faltered now, all that he had gained could so easily be lost. His weakness would be revealed to the enemy, who could last out in Singapore for months, and who had sufficient resources to mount devastating counter attacks once they had regrouped. The time to launch the final attack was now. Not a moment could be lost.

The overriding urgency was to maintain the momentum of the advance until the island and city fell, and not to pause until this had been achieved. Yamashita recognised that more than anything else the battle was now a war of wits. Did Percival realise how weak was 25 Army? Yamashita took the risk that he had no idea how exhausted and vulnerable the Japanese units were and continued to behave on the battlefield as if his supplies were inexhaustible, his manpower undiminished and the morale of his troops unquenched.

Plans for the assault into Singapore across the Straits of Johore were prepared with extreme secrecy. Yamashita ordered extensive deceptive measures to cast a cloak over his intentions. In the west, where Percival had massed the bulk of his troops (two of his three divisions), vehicles on the Johore shore were kept running in a constant loop, lights blazing going eastward, but creeping back on the return journey with lights dimmed, so as to provide the illusion of massive one-way reinforcement of the eastern sector. A false headquarters and signal centre were created in the east, generating large volumes of signal traffic, to reinforce this illusion. Only the weak Australian division, plus two under strength Indian brigades, were left defending the west, precisely where Yamashita planned to assault the island. Troop movement during the day was kept to a minimum; food was cooked miles to the rear and brought up under cover of darkness, the local population forcibly moved, and positions were carefully hidden from aerial observation.

Yamashita’s artillery bombardment began on 5 February, targeting the three northern airfields, the now deserted and evacuated Naval Base, and principal road junctions. Yamashita expertly exploited the psychological dimension of battle. His artillery attacks on Singapore were designed to create panic, and a feeling that the end was near, and that nothing that the British could now do would be sufficient to reverse the situation. This psychological dominance was to do untold damage to the forces expected to defend Singapore, especially those newly arrived and poorly trained. As a consequence, the canker of defeat ran deep in Percival’s broken army during the last week of the battle.

Yamashita’s feint to the north-east with the Guards Division worked even better than he had hoped, Percival being deceived, and shifting the emphasis of his defence to the east. When it became apparent that Percival had indeed been hoodwinked it was too late to repair the damage to his own dispositions.

By the morning of 13 February the Japanese had pushed Percival’s forces back to a twenty-eight mile perimeter covering Singapore City. Yamashita was desperately short now of petrol and artillery ammunition, and it was clear that he could not sustain a long siege. Correctly divining the moral state of Percival’s forces he ordered no let-up on the pressure he was exerting, despite the very real prospect of running out of ammunition and rations.

On 12 February Yamashita had arranged for a message to be dropped to Percival advising him to surrender. No reply emerged until the morning of Sunday 15 February, when men of Mutaguchi’s division reported a white flag in the trees ahead. Yamashita’s bluff had worked and the shaken British were now prepared to parley.

At Yamashita’s insistence Percival journeyed with a small number of his staff officers to the now-silent Ford factory at Bukit Timah late in the afternoon. He was in a poor position to negotiate but succeeded in getting Yamashita to agree to take special measures to protect the civilian population in Singapore and to ensure the maintenance of order and security in the city. In the end a ceasefire was agreed for 8.30 p.m. that day. The campaign was over.

The event was dramatically embellished by Japanese journalists in attendance and painted a distorted picture not just of what happened, but of Yamashita as an aggressive and overbearing bully.

Yamashita spoke no English. He was desperately concerned about the exhaustion of his troops, his shortages of ammunition and the prospect of having to conduct street fighting in Singapore City against a numerically superior foe. Accordingly, he was determined to secure an immediate end to the fighting. Unfortunately, the interpreter attached to his headquarters possessed only limited skills in English. Yamashita instructed him to ask Percival whether he was surrendering unconditionally.

The discussion between the interpreter and Percival that followed seemed, to Yamashita, to be rambling and inconclusive. Losing his temper, he slammed his fist on the table and demanded from the man that he secure a simple ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ from Percival. Yamashita was desperate to secure Percival’s surrender, for any prolongation of fighting would expose Japanese weaknesses to the British. His aggression – both individually and as an army – was, as he admitted pure bluff, but ‘a bluff that worked. He was outnumbered by more than three to one. Shaken, Percival agreed, and tens of thousands of British, Indian, Malay and Australian troops laid down their arms and entered an uncertain captivity.

Militarily, the Malayan Campaign was undoubtedly, for both Yamashita and 25 Army, a remarkable triumph. That he was able to capture Singapore with the loss of only 9,656 men (of which 3,507 were killed) and capture upwards of 120,000 men, made his achievement as remarkable as that of the blitzkrieg that had destroyed France in 1940. Yamashita’s staggering achievements in conquering Malaya and Singapore with such unexpected speed and inflicted a humiliation on Great Britain that exceeded perhaps the disaster of the BEF the previous year.

In my next post, I’ll look at the campaign through the perspective of Lieutenant General Percival.

Very interesting, thank you. I was confused about the two back to back articles, so I first read the one from the perspective of General Percival, which gave me quite a different view of the Japanese side. Having read this now, it was an eye opener.

Some people are simply - either by talent or extensive training - excellent strategists. Yamashita seems to have been such a person, and despite your arguments in the other post about Gen. Percival, in this whole debate, he did seem a good person but not in the right place.

My book backlog is very long, however I added "The Generals" to it. Thanks for the post!