When I was writing my latest book with General Lord Dannatt he said to me, “Rob, if I’ve got one criticism of ‘A War of Empires’ its that you don’t emphasise enough the role of Bill Slim in coming up with the plan for victory in 1945, and executing it perfectly.” Fair. As Slim’s military biographer, I told Richard that I didn’t want to be accused of rewriting that book again. I was conscious of this problem as I was writing A War of Empires.

But it is fair criticism. It may be that I underplayed Slim’s role when I was considering all the other critical features in this great campaign. The idea behind the dramatic victory by 14th Army in Burma in 1945 was Slim’s and Slim’s alone. He pursued his own plan through to its remarkable conclusion.

Anyway, I’ve had the opportunity of reprising 1945 in a new short account of The Reconquest of Burma for Osprey. It is being released on 20 July. I’ve much fun writing it and arranging for some superb new maps and paintings to be commissioned.

Richard’s point was that Slim’s approach to warfare in Burma was refreshingly novel for the British Army of the time. In planning his offensive in Burma he aimed to apply strength - in the form of combat power - against weakness, rather than against strength. In everything he sought to exploit subtlety and guile. At the tactical level he berated those who in 1943 were still trying to solve the problems provided by Japanese defensive tactics by massing infantry for assaults on narrow frontages. At the operational level of war Operation Extended Capital was one of the classic accounts in the history of war of the power of manoeuvre to entirely destabilise the whole basis on an enemy’s plan. This isn’t just me saying so. General Kimura, commander of the Burma Area Army, described it as the ‘masterstroke of the war.’

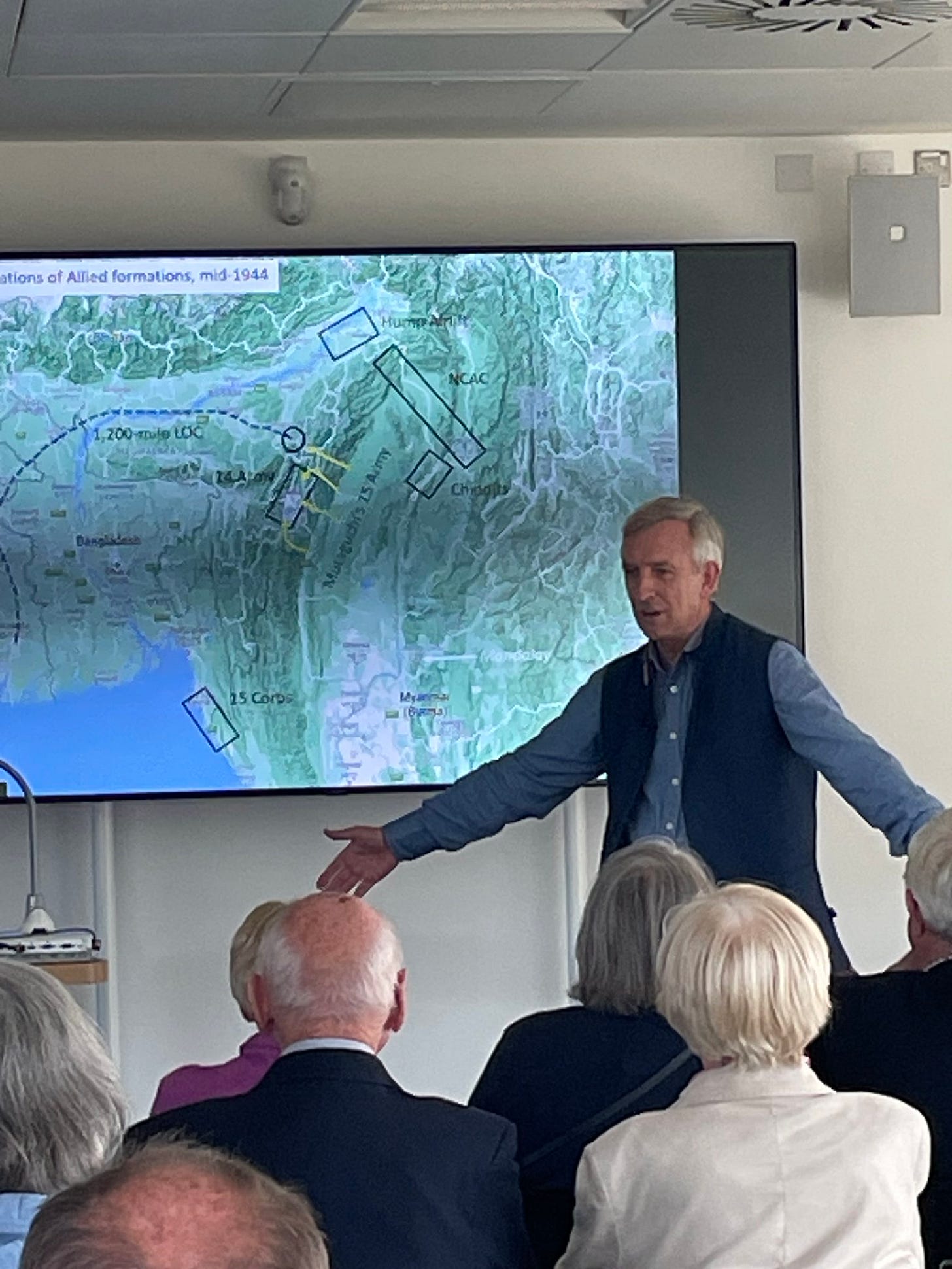

I had the good fortune to be able to describe the brilliance of 14th Army operations in Burma to an appreciative audience at the University of York last week, in conjunction with the Kohima Memorial Service.

Slim’s original plan was to fight the main strength of the Japanese army on the Shwebo Plain, a dry, flat plain between the loops of the Chindwin and Irrawaddy. Not only would the terrain be well suited to the deployment of armour, for which the Japanese had little effective reply, but the Japanese would be trapped with the river-line at their back. Slim had assumed that the Japanese would be unprepared to make a voluntary withdrawal. The scene was set for Slim to be able to deploy his superior mobility and firepower to destroy the main Japanese army in Burma.

By the end of the year, however, it became apparent that the Japanese were not going to conform to Slim’s plan for the battle, and General Kimura had seen the trap which his forces would be caught in if they attempted to stand and fight in the Shwebo Plain. Showing unusual flexibility and moral courage Kimura promptly withdrew his reconstituted 15th Army behind the Irrawaddy. Kimura hoped, not without reason, to be able to smash Slim’s army as it attempted to cross the river, which in itself presented an immense obstacle to the British. He would then counter-attack and destroy Slim as the British withdrew during the monsoon to the Chindwin.

Kimura’s move behind the Irrawaddy destroyed at a stroke Slim’s plan. Undaunted, and recognising the supreme importance of destroying Kimura’s army rather than taking ground for its own sake, Slim came up with another plan. In basic outline, his new plan (Operation Extended Capital) entailed crossing the Irrawaddy and fighting the decisive battle in February in the plain around Mandalay and the low hills around Meiktila, the key enemy air and supply base in Central Burma. Both the road and rail links between Mandalay and Rangoon ran through Meiktila. If Meiktila fell, the whole structure of the Japanese defence of Central Burma would collapse.

But this meant that the 14th Army had to cross a great river which the enemy were holding in considerable strength throughout its length. Since 14th Army did not possess enough equipment to make a strongly-opposed main crossing feasible and to avoid a frontal assault against strength, Slim proposed to make more than one crossing and then deceive the Japanese as to where the real assault in strength was to be made. This was a very audacious concept. Slim decided that if he made a sufficiently strong crossing north of Mandalay, this would draw in Kimura’s forces, whilst the main crossing could be made south of Mandalay, directed against the Meiktila base.

Slim intended secretly to switch his 4th Corps from the left to the right flank of his army, moving it down the Gangaw Valley, building its own road through forest and jungle as it went. It would then mount a sudden, overpowering assault over the Irrawaddy and push an armoured strike force through to Meiktila. The capture of this focal communication area, with its dumps and airfields, would sever the lifeline of both 15th and 33rd Armies to the north.

Slim hoped that these moves would completely unhinge Kimura’s front and disrupt the balance of his forces. If successful, it would lead to the destruction of Kimura’s army. It relied for success upon secrecy, on speed and on taking huge administrative risks. He had to somehow get 4th Corps and its tanks the 300 miles to the Irrawaddy bridgehead, through difficult jungle country and without the benefit of a proper road, and when they got there, to cross one of the worlds greatest rivers. Somehow, 14th Army managed it, in the face of innumerable logistical difficulties, and throughout Kimura had no inkling that he was not faced with two corps north and west of Mandalay.

The rest, as they say, is history. You can read all about it here!

Was your lecture at York recorded online?

Re withdrawal. We agree. I blame a few things along with Slim. One is nature of The appreciation (now estimate). You will have seen it written by Scoones and widely distributed. The structure of the estimate is not much changed even now other than some mission command stuff bolted on the front. The problem is it suggests debate and is not, of itself, an order. Thus, on receipt eg Gracey scribbles contrarian thoughts on their copy. And as you said continued their disagreement even when ordered.