'Wishful thinking does not buy peace, but hard power does.'

General Lord Dannatt and my article in the Sunday Mail today

WHEN IT comes to national defence, never take your eye off the ball. That is a lesson we can and must learn from history. Because the disturbing fact is that this country did just that in the 1920s and 1930s in the aftermath of the First World War and the result very nearly cost us our freedom as Hitler’s forces threatened our shores.

Britain won the war in 1918 but then shamefully lost the peace as our army was allowed to atrophy.

It is often forgotten how professional the British Army had become by 1918, to pull off a stunning battlefield victory over the Germans in northern France in the final Hundred Days of the war.

It had been a long time coming after years of static trench warfare and no decisive breakthrough, just massive loss of life in the blood baths at Ypres, Verdun, the Somme and Passchendaele.

But finally, at the Battle of Amiens, British commanders – often wrongly caricatured as dunderheads and ‘donkeys’ leading lions – demonstrated that they were able to understand and master the intricacies of the modern battlefield. With their sophisticated co-ordination of all elements of combat power – infantry, artillery, air power, armour - the stalemate was broken.

Modern war-fighting skills, technology and methods – learned at great cost in lives over the previous three-and-a-half years - secured victory for the British Army and its allies in 1918 as the Germans admitted defeat and sued for peace.

And yet little more than 20 years later, the boot was on the other foot as the next generation of German soldiers poured into France and defeated the Allies in a lightning campaign that ended with British troops fleeing from the beaches of Dunkirk.

How had victory in 1918 turned so quickly to defeat and humiliation in 1940?

The answer is that it had become the deliberate policy of successive British governments to downgrade the Army - a lesson we must learn today, with a new Defence Secretary who knows little about the brief.

Spending on defence was dramatically slashed amid an ill-thought-through assumption that there would not be another major war within ten years and so.

So far as the then government was concerned, the ‘war to end all wars’ (as the Great War was dubbed) had done its job. There was no need to consider or plan for a future one, whether in policy, financial or practical terms. Everything was an issue of money as budgets were decided by Treasury civil servants with no military advice.

The principal reason why the Army was so unprepared for war in 1939 was that the British government, through faulty defence planning and financing in the previous two decades, made it so.

Significantly, there was all-party consensus on this. With economic recession and depression to contend with, the Conservative, Liberal and Labour parties were all reluctant to stop the cuts and or to argue for more expenditure on defence.

Nor was there any popular outcry.

If a country became less warlike, this argument suggested, potential threats would simply disappear into an ether of goodwill.

This was a virus of wishful thinking of enormous potency and equally considerable naivety.

And so the British Army fell asleep at the wheel, slipping back into being an imperial policeman whose job involved relatively simple technological requirement in terms of weapons and equipment.

However, it is the duty of government, then as now, if its takes the security of the nation’s interest seriously, actively to imagine the unimaginable and prepare for it.

Similarly, in January 2022, a war in Europe was both unthinkable and unimaginable, but it became a reality when Russia attacked its neighbour, Ukraine.

History has an uncomfortable habit of repeating itself.

It is, perhaps, little wonder that Vladimir Putin sensed that the West, once united during the years of the Cold War, was ripe for challenge as he saw Western military capability being atrophied in Europe and diverted elsewhere in forays against militant Islamist movements in Iraq, Afghanistan, the Middle East and Africa.

He may have taken some comfort from the West’s eventual disappointments in Iraq and Afghanistan, and he was undoubtedly emboldened by the precipitate flight of the US and NATO’s undignified exit from Kabul in August 2021.

This is where recent events uncomfortably mirror those failings in defence policy and preparation between the First and Second World Wars.

In the 1930s, the liberal democracies of the West set their faces against rearmament and chose negotiation and appeasement as their response to Hitler’s Germany.

The Ukraine war represents another moment when Western leaders, and those of the UK in particular, are faced with a dilemma to know how to act appropriately.

They can choose to bury their heads in a moment reminiscent of the appeasement of Hitler at Munich in 1938 or embrace difficult and expensive choices, perhaps not popular in the short term but likely to be a sound investment in future security.

Accepting that Ukraine was not a member of NATO and therefore not under the umbrella of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, Western states, nevertheless, have stood solidly in support of Ukraine as it fights to protect its independence, sovereignty and preferred way of life.

But should it have come to this? Had the cautionary tale of the past not been heeded? Had the absence of a response to the rise of a dictator in Europe in the 1930s been mirrored by the hesitant response to the rise of a dictator in this decade?

This is the challenge to Western governments - and to Britain in particular if it wishes to substantiate itself as a major player on the world stage in the years to come.

As a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, it is difficult to conceive how the United Kingdom can duck these responsibilities, but rising to them comes with a price.

In March 2021, the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy posited a geographic tilt on Britain’s defence strategy towards the Indo- Pacific region. It also gave priority to new technologies and new ways of warfare.

However, a brutal land war in Europe has proved to be a rude wake-up call with Putin’s assault on Ukraine taking war back to its bloody basics.

So, what should be the response of the British government in the face of current events?

For a start, defence spending should rise from 2 per cent of GDP to closer to 3 per cent. And much of it needs to be spent on a major investment in the UK’s land power capability.

Planned cuts to the size of the Army should be questioned, as should decisions to reduce helicopter and tactical air lift capabilities. The Challenger 3 tank modernisation programme should be accelerated, and the numbers significantly increased from the paltry plan of just re-fitting 148 main battle tanks.

The removal from service of the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle should be stopped and a full modernisation programme embarked upon.

Moreover, as the war in Ukraine has shown, rocket and tube artillery numbers need to be dramatically increased as does air defence capability to meet conventional aerial threats but also the new weapon of armed drones.

Underpinning all this must be a modern and secure communications system supported by robust logistics and adequate holdings of ammunition and other combat supplies.

Without these enhancements and more, we will be unable to play our part in the future deterrence of further aggression from a newly aggressive Russia.

Wishful thinking does not buy peace, but hard power does.

The history of the 1930s showed the folly of not acting in a timely manner while the draining away of the UK’s military capabilities since the end of the Cold War shows a remarkable tendency to allow history to repeat itself.

Defence expenditure is the insurance premium that any responsible government must pay to protect the security of its territory, its national interests and its people. The premium may have just gone up, but the alternative is a disaster. Ukraine is Europe’s wake-up call. We must listen and act. We might not be given a second chance – again.

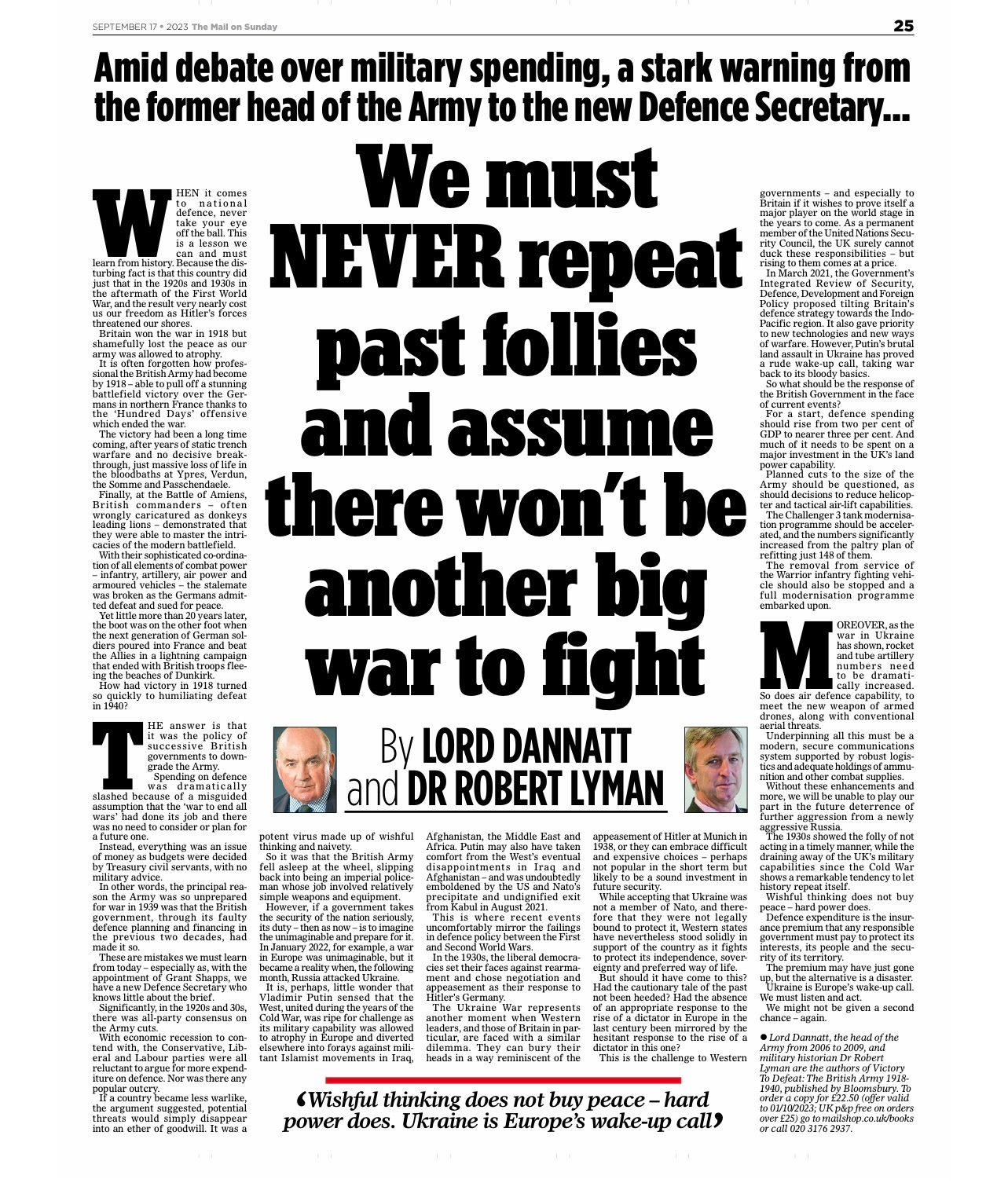

Lord Dannatt was head of the Army (Chief of the General Staff) from 2006 to 2009. Dr Robert Lyman is a military historian

Adapted from Victory to Defeat: the British Army 1918-1940 by Richard Dannatt & Robert Lyman (Bloomsbury, £25) to be published 14 September. © Richard Dannatt & Robert Lyman 2023. To order a copy for £22.50 (offer valid to 01/10/2023; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

I fear that, in general (not in UK), such behaviour is enabled by the population, and it's not purely political. Here in Switzerland, the "Group for a Switzerland without an army" is sometimes getting enough votes to almost push some things through. I can't believe that all people supporting them are part of a "fifth column", so for a normal person, I can't fathom how they can think not having an army at all makes _any_ sense, in any world, ever. But there are such people, so shrug…

And it's not just such a fringe group. In a recent poll (in the context of the upcoming national elections), most left parties are saying that the army should focus on helping when natural disaster strike, shrinking the army even further, etc. etc. It basically forces one to vote right-wing if they care anything at all about security - sigh.