To War with Cuthbert

Virginia Hall and La Resistance Française

hat F (‘France’) Section of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) sent its first spy in August 1941. They designated the mission ‘Geologist 5’ and gave their agent the code name ‘Marie’. Her name was Victoria Hall. A 34-year-old American, she was described by a badly burned RAF pilot – Flight Lieutenant William Simpson – who met her later that year in France as having ‘light-brown hair drawn back straight to a bun, with the features of a cavalier; a rather long and aristocratic face with beautifully calm eyes, which nevertheless usually twinkled in friendly circumstances… tall, slim and handsome with a straight bold carriage…’. SOE had stumbled on her in early 1941, when she had managed to make her way out of France in 1940, quickly recognizing her abilities and the opportunity that she, a citizen of a still-neutral United States, could offer Britain by becoming its eyes and ears in a country from which they now had little or no acquaintance. But Simpson couldn’t work out what inspired Hall to put herself in harm’s way. Why volunteer to return to France to work underground for a country not her own, and against an enemy that was not yet her country’s enemy?

The opportunity for encouraging resistance among the mass of the French population was an early aspiration for the British, labouring under the expectation that the whole of France seethed with righteous indignation against their Teutonic occupiers. But in almost all respects the British misjudged and misunderstood the situation in France. Organized internal resistance in France to German occupation in fact took years to establish, and when it did its effect on the Allied war effort was minimal. At its high point in 1944 military resistance more often proved a distraction to the Allies, and merely an irritation to the Wehrmacht. Nowhere, not even – especially not – in the confused liberation of Paris in August 1944, was it a decisive instrument of war. Ultimately, la résistance française was hijacked by General de Gaulle for political purposes, a convenient narrative in 1944 to provide a pretence of national unity, a salve for post-war political and imperial endeavours. From the armistice on June 22, 1940, until the establishment of the General de Gaulle’s Forces Françaises Combattantes in 1943 and the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR) that same year, and then the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur, or FFI, in 1944, resistance was a hotchpotch of individual and small-group effort, few with any strategic purpose and little or no unity, often with competing groups squabbling for recruits and prisoners of competing egos and agendas. Most resistance was political, especially in its early ears, only later (in 1944) did military resistance emerge in any significant degree. Indeed, studies of la résistance in this period would do better to understand its absence.

Its fair to say that between 1940 and 1943 there was no effective military resistance in France. The country had been completely undone by its comprehensive military defeat in the six-week war of 1940 and the political escape-clause in the armistice that allowed the French the belief that de jure government continued under its head of State – Marshal Petain – and the government in Vichy. At least, so most people thought in 1940, the Armistice had allowed some honour to be plucked from defeat, as France continued to control its colonies and its fleet. In this context collaboration – active political, economic and social alignment between France and Germany – made eminent sense, not as an imposed direction from Berlin, but as a self-generated policy of supplicatory cooperation by Vichy. Collaboration was legitimate; resistance was not. Those – like General de Gaulle, now in London – who carried on the fight after the armistice were now considered to be themselves rebels and renegades, hostile to peace. With Britain soon to go the same way, why fight against the inevitable? Better, so the thinking went, to start creating the post-war environment of cohabitation now. It was a policy so-called of pragmatism, although of course it was nothing of the sort. The greatest failure of this warped thinking lay in the assumption that Germany was not in the process of imposing a new and violent racial hegemony on Europe. For the Petainists, 1940 seemed to be merely the extension of an age-old Franco-Germanic rivalry, not the existential threat to world peace that Nazism in actuality presented. But it explains why, in 1940 through to 1943, there was little appetite for active resistance in France. Hatred of Britain was reinforced in many quarters after the action at Mers-el-Kebir on 3 July, when the Royal Navy opened fire on the French Mediterranean Fleet, killing many sailors and giving credence to the Petainist argument that Britain – because of its continuing, active warlike activity – was the real enemy to peace in Europe.

The French experience of occupation also tended to reinforce the feeling that this war wasn’t that of 1914-18, that the German policy of Korrektheit was in fact one of mutual respect between Frenchman and German, that the old warlike hostilities were a thing of the past. In this make-believe world occupation and collaboration could actually be, despite the food shortages and other exigencies of war, not entirely unpleasant. In the context of the very early days of occupation and Petain’s political policy of collaboration with Nazi Germany it is hardly surprising that many in France who were naturally inclined towards resistance struggled at first to find an expression for their opposition to the enemy occupation, lost in a confusing world that had seen all of its certainties removed. It is not hard to understand the profound sense of social and cultural discombobulation experienced by most French people in 1940. How were they to behave now that the France had been humiliated on the battlefield, the Third Republic was no more, and they were under comprehensive military occupation? If they were to rebel, how were they to do it? And was rebellion against Vichy itself morally virtuous, or even legal, given its craven subservience to the totalitarian impulses of Petain, Laval and Darnand but where an alternative government wasn’t immediately apparent? This feeling, for many, continued to the end of the war. The historian Allan Mitchell describes the close personal and professional relationships that developed between German and French authorities as ‘the long handshake’, a ‘lengthy silent clasp of hands’ of administrators joined by their professionalism regardless of the political or military turmoil that threw them together in the first place. To them collaboration was not a pejorative term but, like the German soldiers helping French farmers bring in the harvest in the autumn of 1940, signs of a deeper, fraternal relationship that reflected the natural cooperation of brothers now that a hasty argument had been settled.[1]

Accordingly, the first year of German occupation was one, according to resistant Gilbert Renault (‘Colonel Remy’), when ‘those who intended to resist . . . were still groping for each other, not knowing yet how best to harm the invader’. The dramatic social and political divisions in France at the time, exacerbated by the confusion of defeat, mean that resistance, when it emerged, had many parents, and struggled for several years to find a united voice. Kenneth Cohen of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) described the early resisters as ‘a minute elite (who became known to us as vintage 1940)’. De Gaulle’s Free France movement based in London provided one rallying cry, but his voice took a long time to be accepted as the genuine or primary expression of French liberation. Certainly, his call to arms on the BBC on 18 July 1940 was ignored by the vast bulk of French servicemen evacuated to Britain (to whom the call was pre-eminently made, rather than to the people of France), most choosing to be repatriated to France. For many people in France, as well as policymakers in Washington, he never succeeded. A relatively junior officer, de Gaulle was virtually unknown in 1940: his greatest challenge was to persuade a cowed and divided nation that he had the right to speak on their behalf. In particular, in 1940 the people of France needed to know that they could place their trust in something more than a phantom, when their existing political leadership – of all shades and hues – had so spectacularly failed them.

The limited resistance in 1940 and in the years that immediately followed were expressions therefore of political rather than military rebellion. By the end of 1940 six underground newspapers were being printed in the zone occupée, the first sign of public challenge to the occupation, and anti-German and anti-Vichy clammerings could be heard in the Vichy zone libre, many from the traditionally rebellious city of Lyon, which became known as the capital of the resistance. Le Coq Enchaîné, France-d’Abord, Témoignage Chrétien, L’lnsurgé, Combat, Franc-Tireur and Libération (Sud) emerged in the south, and in the north the Organisation Civile et Militaire, Libération (Nord), and Ceux de la Résistance, brought together non-communists (most of whom belonged to the Parti communiste de France, PCF) from a wide variety of backgrounds, professions, economic status and political views into the business of creating the authentic voice of anti-German and anti-Vichy resistance. Combat, Libération and Franc-Tireur were established respectively by ex-army officer Henri Frenay, Emmanual d’Astier de la Vigerie, and Jewish businessman Jean-Pierre Lévy eventually merging to form the MUR, or Mouvements Unis de la Résistance. Numbers, though, remained small and in the manner of disparate self-generated organizations had a wide range of aims, ambitions and competences, some of which conflicted with each other. Many, indeed, were rivals. An example of an early reseau in the zone occupée, begun in Paris in the late summer 1940, was based upon a group of friends who worked at the Musée de l’Homme, housed in the massive Palais de Chaillot on the rue du Trocadéro overlooking the Seine. The first efforts of this group, led by Anatole Lewitsky (an anthropologist), Boris Vildé (a linguist, who had escaped early German captivity) and Yvonne Oddon (the museum’s librarian), were to disseminate anti-German literature, produced on a printing press in the basement of the museum. This became the newspaper Résistance.

Early groups tended to reflect the political allegiances of their founders, and naivety and amateurism were their greatest enemies, especially when faced with the discipline of the Abwehr and the monetary incentives offered by the Germans to Frenchmen to inform on their neighbours, a cunning device that demonstrated just how acute was German understanding of the gaping crevices in the fabric of French political life, where some factions hated each other more than they hated the Boche. The very existence of Petain’s Vichy was testament to the seemingly irreconcilable fractures in French society. Suspicions abounded, denunciation a powerful tool. Henri Frenay recalls that even his own mother threatened to denounce him. As a result groups were often formed of tiny circles of family and friends, representing limited self-interest and with very small pools of support and no real connection to the mass of the people. The little coordination that was attempted amongst the reseaux that emerged in the early days tended more often than not to end in disaster for the organizations that paired with each other, as they were easily infiltrated and destroyed by German (mainly Gestapo and Abwehr) agents provocateurs. This proved the greatest threat to nascent groups emerging from the confusion of defeat, and feeling their way to meaningful expressions of resistance. But what did take place were the foundations – in terms of bitter, learned experience – for what was to follow in 1944 and 1945. In any case, throughout the four years of occupation in France only a tiny fraction – certainly far less than 1% – of the French population of some 40 million resisted in any formal sense. Most people just kept their heads down in an attempt to survive. One estimate of the total number of résistants in 1942 across France puts it at no more than 4,000.

Much of the (very little) resistance undertaken in occupied France in 1940 and 1941 did so as spontaneous reactions by individuals humiliated by German occupation and angered by the collaboration of their political masters. In this sense it can be regarded perhaps, as the historian Julian Jackson suggests, as a continuation of the fighting of 1940 rather than the start of a new war of resistance. The most common involved individual acts of protest such as anonymous graffiti, vandalism of German and Vichy posters, the cutting of telephone and electricity lines and the slashing of tires on unguarded military vehicles. On August 13, 1940, barely two months after the occupation had begun, a German sentry was shot dead outside the Hôtel Golf in Royan in Charente-Maritime. In reprisal, the German authorities rounded up several prominent citizens and imprisoned them indefinitely as hostages against the threat of further ‘terrorism’. On August 22, in Bordeaux, a 32-year-old docker, Raoul Amat, allowed himself to be caught slashing the tires of a German truck, and was sentenced by a military court to thirteen months’ imprisonment. On September 17 the mechanic Marcel Brossier was executed in Rennes for cutting electricity cables. Others merely shook their fists – and lost their lives for it. On Saturday August 24, Leizer Karp, a refugee Polish Jew, shouted abuse at German military musicians playing near the Saint-Jean railway station in Bordeaux. Taken into custody, he was transported to Sougez camp and sentenced to death. He was shot two days later.

It was the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 and its subsequent occupation of the zone libre following the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942 that was responsible more than anything else for turning the tide of French popular support towards the idea of formal, active resistance. Operation Barbarossa was especially significant, in that it solidified communist opposition to the occupation, prevented until then, on Moscow’s explicit instructions as a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact. With this restriction lifted, direct action quickly grew, but mass protest failed miserably. The industrial region in the north was the centre of communist-inspired resistance after mid-1941, with a strike by coal miners in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais region between May 27 and June 6. But the communists had badly misjudged the tenor of the German response: this was no benign occupation, as two hundred and fifty miners discovered to their cost when they were forced at gun point into cattle trucks and transported to Sachsenhausen. Equally, the process of amalgamation or consolidation of the various resistance factions moved a lot faster after the German occupation of the zone libre in November 1942, which turned many towards active resistance, as people found solid, rational grounds for rejecting the collaborationist imperatives of the Vichy regime as well as the aggressively right-wing policies established by the pro-German dictatorship of Pétain’s ‘Etat Français’.

A small number of assassinations of Germans took place, which triggered vicious reprisals authorized from Berlin, Hitler insisting that a hundred Frenchmen be executed for every German killed by the Resistance. On August 21, 1941, Pierre-Georges Fabien of the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans Français (FTPF) assassinated a German officer on the Paris Métro, and Colonel Karl Hotz, the Feldkommandant of Nantes, was shot dead on October 20 by a three-man FTPF hit squad. Dr Hans-Gottfried Reimers, a senior member of the Wehrmacht’s civilian staff in Bordeaux, was shot dead on October 21, 1941 by a team of young communists who had travelled to Bordeaux by train from Paris for this purpose. The German response was savage: forty-eight hostages were shot on October 22 in reprisal for both attacks.

Most of the attacks and acts of sabotage carried out in France by the Resistance during 1941 and 1942 took place in north-eastern France, but by far and away the largest proportions of execution for terrorism took place in the final years of the occupation. The Germans shot 1,143 Frenchmen in Lille and the Arras Citadel alone. In the course of time it is estimated that some 30,000 résistants in France lost their lives, executed in France or deported to concentration camps in Germany, there to disappear without trace under the deliberate policy (‘Nacht und Nebel’) of secret execution and the disposal of evidence (usually by cremation) ordered by Hitler on December 7, 1941 and carried out with alacrity and efficiency by the German state.

The fundamental absence in 1940-41 for what posed as the disparate splinters of la resistance française was focus, orders, discipline, unity, a sense of self, organization, purpose and direction, as well as money and supplies. It required an external well-spring, of the kind that could only be provided by London. There was a symbiosis here that benefited both parties. London urgently needed to see inside France, and résistants in France needed to reach out to London for the regular transfusions of life-blood they required even to survive. Into this beneficial nexus came Virginia Hall. Her file in the National Archives in London records that the Baltimore-born Hall, previously an employee of the United States Foreign Service who had served in a number of embassies across Europe, had come to the notice of the SOE in early New Year 1941. A British agent had sidled up to the 5-foot 7-inch tall red-head at the Spanish border town of Irun in August 1940, Hall explaining that she was attempting to make her way to London. The agent – George Bellows – taken by the intelligent lucidity and obvious capability of this woman who was fleeing the collapse of France following service as a volunteer ambulance driver in the Service de Santé des Armées, gave her the telephone number of someone who might help her find employment in London.

When Hall arrived, she called the number, and was invited to dinner by Nicholas Bodington and his American-born wife, Elizabeth. Before working for SOE Bodington had been Reuters's press correspondent in Paris, and now worked in the nascent France (‘F’) Section of this new organization established by Churchill with a remit of keeping alive the spirit of rebellion and resistance among the countries of occupied Europe He, too, was taken by Hall, and on January 15, 1941 wrote a memo on his meeting to the F Section recruiter, mystery-writer Selwyn Jepson, who was especially looking for woman-agents to send to France. Jepson was later to recall that in SOE he ‘was responsible for recruiting women for the work, in the face of a good deal of opposition… from the powers that be. In my view, women were very much better than men for the work. Women… have a far greater capacity for cool and lonely courage than men. Men usually want a mate with them. Men don't work alone; their lives tend to be always in company with other men.’[2] Bodington mentioned that Hall had indicated an interest in travelling to France to see what was going on, and that SOE should use this opportunity to see ‘what service she could render us.’ The wheels of espionage planning turned slowly, and it wasn’t until June that it was agreed that Hall would go to France under cover as a journalist accredited to the New York Post; that she would base herself in the spa town of Vichy, close to the seat of French government in the zone libre, and that she would send back to London any intelligence she felt might be useful to the British war effort. Her task, noted in her SOE file, was ‘to provide intelligence about conditions etc. in France, to develop various contacts with a view to the resistance possibilities, to act as [a] channel for transmission of instructions to F Section agents, and to look after agents generally.’

The truth seems to be that while Jepson knew that he needed an agent in the unoccupied zone, he didn’t really know what they should do, and left it to Virginia to determine for herself the role she felt the situation best required. It could be collecting intelligence about Vichy and German military, political and economic issues, coordinating the activities of other SOE agents as numbers built up over time, building up a network of informers and intelligence-gathers in France, assisting with the return of escaping and evaders Allied servicemen, arranging air drops of supplies and so on. These rather general instructions – to establish networks, réseaux in French – was given to the first and early SOE agents who began arriving in France in May 1941.

After training in spycraft at Wanborough Manor, Arisaig and Beaulieu she departed for France, via Lisbon, on August 23, 1941 using her American passport, but with the nom-de-plume of Brigitte LeContre up her sleeve, carrying a million francs beneath her voluminous skirts. Her SOE code name was Germaine. Flying on a Lufthansa plane to Barcelona, she then caught the train to Marseille before journeying on to Vichy. From the outset Hall’s position with the New York Post was a subterfuge, a situation tacitly endorsed by the newspaper’s editor, George Backer, which allowed her a reason to be in France in the first place. She would have to submit just enough articles to the newspaper to maintain her cover. Of course, nothing would protect her if she was caught inflagrante.

What the file does not record, possibly because it was so prosaic that it didn’t matter to those compiling these records – or that people simply didn’t know – was that Virginia Hall had a 7-pound wooden left leg, complete with a hollow aluminium foot, which she called Cuthbert. She had lost the leg in December 1933 in a shooting accident whilst out hunting snipe when working at the U.S. Consulate in the Turkish port city of Smyrna, but she had entirely mastered the art of covering up the fact that she had lost a lower limb. Her rapid and determined recovery from such a devastating experience marked her out as a woman of unusual physical and mental courage. Long skirts and an equally long stride that enabled her to walk without an obvious limp meant that few people were aware of what would have been considered a serious physical handicap for someone seeking to undertake secret operations behind enemy lines. In fact, it is entirely possible that in 1940 no one – or at least very few people – at SOE had any idea that she had a prosthetic leg. A questionnaire in her SOE Personnel File (‘Form CR1’) which she completed in 1943 had a dismissive line through the answer section to the question: ‘Please mention any serious disabilities or past illnesses’. She kept her secret very well, knowing full well the prejudice that many had to the differently-abled, especially those who were women. Being a female in the chauvinistic world of secret intelligence – Hall was SOE’s first female recruit – was bad enough. The less said about her prosthetic leg the better, seemed to be her attitude. It didn’t get in her way, and she didn’t see why it should bother anyone else. In France, however, she couldn’t entirely hide the fact of her disability and she was soon to be known – by friend and foe alike – as la dame qui boite: the lady who limps.

With Hall’s appointment SOE had struck gold, for in addition to being a woman of powerful drive and determination she was a stupendous organizer, and precisely the person SOE needed at this juncture to add clarity, resourcefulness and purpose to their efforts to understand what was going on in France, and to put in place networks, organizations and structures to sustain a long campaign of anti-German subversion in the country. She was also a person able to operate alone, depending on her own resources, ingenuity and stamina to stay hidden, and to stay alive. Her status as an American gave her priceless cover as a citizen of a neutral country. Hall was a woman who enjoyed doing things, and getting things done, and having things done her way. The historian of SOE, M.R.D. Foot, exaggerated slightly by describing her as having a ‘fiery temper.’ She certainly had forthright views, but none of the available archival or other evidence suggests that her anger, when roused, was ungovernable. The truth was that she had no fear of making decisions, or of giving orders and in this respect she possessed many of the characteristics of successful agents. She had a strong personality, enjoyed taking responsibility, and possessed just that balance between caution and self-confidence that enabled her to remain out of German clutches during two separate sojourns in France. These amounted to three years as a secret agent, the first for the British SOE and the second for the American OSS.

Her privileged upbringing had gifted her three years of study in Paris and Vienna in the late 1920s, learning fluent but heavily-accented French, Italian and German (she also spoke some Russian), as preparation for what she hoped would be a long career in the American Foreign Service. Her hunting accident cut short that aspiration, leaving her open to other adventures, the biggest one of her life coming with the declaration of war between France and Britain and Germany, on September 3, 1939. As with many others, such as Elizabeth Deveraux and Charles Fawcett, she rushed to join up, the only openings at the time for untrained volunteers being either a volunteer in the French Army’s ambulance corps or the ambulance unit of the American Field Service that was resurrected in France in 1939 to provide a response for American volunteers in Paris. Perhaps it is this that partly answers the question William Simpson had asked himself about Hall’s motivation. From childhood Hall had been adventurous, taking for herself opportunities for personal freedom of action and behaviour wherever she could find them. She refused to accept rules and barriers that limited her freedom of action when there was no rational place for them, such that she rebelled when she saw liberty being forcibly denied to millions of Europeans. It isn’t right merely to categorize her as a rebel, or simply as an adventuress, as both terms fail to do her justice. She never saw the war as a game, for instance. Victoria Hall was in fact a lover of liberty. It was an important feature of her sense of being American, with everything that came with the idea of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ and because of this was determined to stand up for the freedoms she herself took for granted when she saw these being so egregiously denied to others.

The reports she filed first from Vichy and then from Lyon demonstrated her outspokenness from the outset. None of the many absurdities involved in living in Vichy missed her penetrating gaze. If she had tried her hand at this for much longer, it is possible that her reports would have led to her accreditation being revoked and her being requested to leave the country, ending her real work at a stroke. She was, of course, using these reports to alert SOE to the realities of life in Vichy France, given that until her arrival what was happening in the zone libre was a complete mystery to London. Her first article, published by the New York Post on September 4, 1941, complained that Vichy was a backward town, too small for the hordes of civil servants who had over-filled its limited hotel space. It had no petrol for cars (and hence no taxis), and there were no clothes to buy, no butter and very little milk. In a beautiful little stab at the absence of consumer necessities, she observed nevertheless that shoes were ‘abundant and gay with their cloth or crocheted uppers and painted wooden soles.’ This, however, was merely poking fun: a much more serious noose into which she placed her head was an article she wrote in November, reporting the repression that Jews now experienced in Vichy France and explaining that a law had been passed forbidding Jews to become stockholders, barbers, publicity agents, merchants, or real estate agents or owners. The few other articles that followed all emphasized the dramatic reduction in foodstuffs available to ordinary people. This type of reporting would have been sufficient to eject her from the Reich. It was perhaps fortunate that as the pressure of her espionage duties increased her writing diminished as, had they discovered it, this type of semi-satirical expose of the limitations of the new France would not have been appreciated by the Vichy authorities, nor indeed the Germans. In fact, it was the German declaration of war on the United States on December 11, 1941 that finally put paid to this subterfuge, though she rather cheekily sent her last dispatch to George Backer in January 1942, published on January 22, from “somewhere in France”. She took her gloves off, reporting without irony (given that she was herself an enemy agent, operating outside of French law) that general lawlessness, evidenced by petty larceny, theft of food and transport, had assumed undreamed-of proportions. The excuse was hunger:

From statistics compiled last summer by a well-known doctor in Lyon, the average loss of weight at the time was 12 pounds, 12 ounces per person.... This doctor however, insisted that not lack of food alone was the cause of the loss of weight. Two other factors play a great role: increased physical activity and mental strain coupled with moral suffering.

People who used to ride in taxis or private cars or even street cars now walk or ride bicycles, and housewives spend hours standing in line to get provisions for the kitchen, all of which is very slimming.

Then, too, many families are divided brutally, part living on one side of the demarcation line, part on the other.... And many sons, brothers, fathers and fiancés are still prisoners in Germany.

Naturally, people who are separated from those they love, whose relatives are still prisoners, living under constant mental strain, which reacts upon their physical condition.

Within two months of her arrival in France she had decided that relocating south to the major industrial city of Lyon would give her much more freedom of movement than Vichy, especially as it sat astride the major roads and railways between the south coast and all routes north and east. Lyon included a large diaspora of Parisian intellectuals, as well as displaced people from all over occupied Europe, adding to a heavily unionized industrial workforce and a wealthy business and middle class. Pre-war, it was also a centre of the book and publishing industry. Given these ingredients, together with its proximity to Switzerland, it was the obvious place for Hall to hide. It would have been hard for her not to notice what was going on around her, as the subterranean undercurrents of rebellion coursed through the streets. She would also be hidden by the anonymity of the big city. In November 1941 she wrote to Boddington:

I’ve moved to Lyons, which is a much better idea. I can go and see things from there, and I’ve made such a lot of friends, doctors, businessmen, a few newspaper people, refugees, professors. One nice doctor has a chasse nearby so I’m shooting again – I shall keep Cuthbert well out of the way.[3]

The roots of what were to become some of the most significant resistance groups in the zone occupée, emerged in Lyon in 1940 as expressions of rebellion by small, politicized groups angry not just about the obvious fact of military defeat, but in response to the imposition on the rump of France left ostensibly to govern itself of a new brand of French fascism, something many regarded as a right-wing coup using the German invasion as a cover. The scale of this rebellion was nevertheless miniscule, the most productive energies were spent in the publication of underground newspapers and leaflets. What became the left-wing Franc-Tireur began in November 1940 with the distribution of leaflets: within a year these became a newspaper, the first 5,000 copies of which were distributed in December 1941. Likewise, Libération began its life in July 1941 with a poster campaign across the city. The newspaper Combat, likewise, first appeared in December 1941. By the time Hall arrived in a city massively swollen with refugees at the end of 1941 Libération, Combat and Franc-Tireur and other organisations, such as the Jesuit Cahiers du Témoignage chrétien remained tiny, swimming desolately in a sea of popular apathy amidst the harsh reality of German military dominance in Europe, and French military and political humiliation. For most people, even the idea of rebellion was a waste of time, given its apparent futility. Likewise, the uniqueness of the wellsprings from which these groups had sprung led them until the arrival of Jean Moulin in his Gaullist unifying mission in 1942, to have nothing to do with each other.

But the problem with most French people, as Hall acutely observed in a report to London in April 1942, was fear:

Laval’s return [to power in Vichy] has caused the rise of a lovely tide of hate and the Marchal’s stock has slumped very sharply. The army is disgusted with its new head, but there is so much apathy and fear in the country that there has been no decided reaction – nothing spectacular, that is, although everyone who was on the fence before has gone over to whatever is against Laval. He has brought you a lot of partisans. Unfortunately everyone fears internment or prison or, in spite of violent language against the government, ask but their daily bread and to be left in peace. The French have got the habit of meekly accepting during the past year. They have accepted stricter and stricter rations, lessening of rations, restrictions on wine, less bread, less alcohol, no beer, until finally they have arrived at the state of eating rutabaga for supper, washed down with mineral water – no beer or wine is served in the evening with the meals (or without for the most part) meekly and without a murmur. It is incredible but true.

At the point at which Virginia Hall was becoming intensively involved in Lyon for the British ‘F Section’ an attempt to unify the disparate resistance movements under de Gaulle was underway, led by Jean Moulin.

During her year in Lyon Hall sat at the beating heart of nine separate circuits, providing coordination, resources, cash and connections – via her pianistes – with London. The first was Heckler – her own circuit – together with Spruce (September 1941), Ventriloquist (October 1941), Tinker (May 1942), Scientist (May 1942), Juggler (July 1942), Marksmen (July 1942), Monkey Puzzle (July 1942) and Detective (September 1942). In addition she supported agents from other groups, such as Newsagent, Tiburce, Prunus (in Toulouse) and Stationer (in the Jura mountains). Hall effectively established herself as SOE’s resident coordinator in Lyon, running her own réseau as well as supporting every other SOE interest in the region, such as developing and funding homegrown reseaux, Gaullist or otherwise; arranging safe house and accommodation for transiting agents or evading or escaping servicemen, providing radio facilities and facilitating parachute drops, providing, contacts, money, intelligence, false papers, food coupons and security and being general dogs body and quartermaster combined. She seemed to be everywhere, to know everyone, and to be able to solve every problem. Her tasks were ‘quite as dangerous as actual sabotage, and much duller,’ notes M. R. D. Foot, ‘but without her indispensable work about half of F Section’s early operations in France could never have been carried out.’[4] Theirs was the task of nurture and growth, providing radio transmitters when these scare commodities were available, arranging for air-drops of weapons and explosives (although in truth these just gathered dust and rust in the early years of the resistance), building blocks of the armed resistance that was to rise up in 1944. In the meantime, these tiny groups, operating within the behemoth of double totalitarianism – both Vichy and German – nurtured the idea of rebellion, even if, at this time, it involved hiding (and facilitating hiding) rather than fighting. Much of this early effort entailed enabling flight: that of Allied servicemen, Jews, Freemasons and communists en route to Spain or Switzerland. As the slowly degenerating clumps of sweaty gelignite and rusting bullets testified, the role of fighting was still far off in the early days of 1942. When 1944 was eventually to emerge from the distant future, the world looked very different to what it had been only two short years before.

Her role in coordination, planning and direction extended from providing warehousing facilities for supplies in Marseille, Avignon and Paris; providing radio operators in Lyon and Paris, arranging air drops and landings by the RAF of weapons, ammunition, explosives and cash. True to her initial instructions she communicated everything she deemed important about life around her to London, gathering information about the Germans, as well as the nascent resistance groups. It was the fact that she was a representative of London that enabled her to see into, and support, the birth pangs of several of these groups, giving them access to rare and precious pianistes, and so for the first time allowing them access to London, the well-spring of life and hope. They caused her headaches and heartache, too. Many of the French leaders she encountered were idealists, some even fantasists to some degree, and few were organisers of the kind necessary to be truly successful in promoting resistance as a fourth arm of the fighting services. Still she persevered, despite the constant let-downs of men whom she did not believe could be trusted with the mission of mobilizing the French people to cast of the Nazi and Vichy yoke. Enough of her contacts proved of value, however, for her not to be downhearted for long. One was Mademoiselle Suzanne Bertilion in Vichy, where the presence of Hall in her first few months inspired her own kind of resistance, one that led to leadership of the resistance reseau ‘1942 H.I.H.I.’ and management of 90 résistants:

On 1 July 1941 I was appointed chief censor 2nd class in the foreign press section of the Ministry of Information at Vichy. The new position afforded me the opportunity to enter into relations with representatives of the American press. A modern Christopher Columbus, I discovered America in Vichy – a circumstance which I considered most fortunate. I had to do with intelligent and conscientious newspapermen whose articles and cables reported the true spirit of France, of a France that had not accepted defeat, nor, above all ‘collaboration’ with the enemy.

She became a valued source for Hall.

By August fifteen men had been dropped in by parachute or had been delivered off the southern coast by felucca, one of the small, inconspicuous wooden sailing boats ubiquitous in the eastern Mediterranean, flitting between Gibraltar and remote beaches off the southern French coast. From the outset they found themselves battling the Sûreté, as well as the Abwehr and Gestapo as the tentacles of those organizations increasingly, throughout 1941 and 1942, inveigled their way into zone libre in order to crush all manifestations of anti-German activity.

Between her arrival in Lyon in November and her departure through Spain the following December, Virginia Hall made herself the indispensable linchpin of SOE operations in southern France, a coordinator and manager extraordinaire of an increasing volume of subversive activity by SOE as the organization felt its way, slowly but surely, to deliver on Churchill’s instructions to ‘set Europe ablaze.’ Through the ups and downs of the maturing clandestine effort on the zone libre it was she who saw, organized and managed everyone else and by her deftness and foresight kept the sometimes-creaking structure stable under the determined onslaughts of the enemy. Her especial strength lay in persuading men and woman to support her own reseau, code-named Heckler, and creating a loyal band-of-brothers between a disparate group of people who had only one thought: to work with this vivacious American to defeat the forces of Petain and, through them, those of the hated Boche

While lying in a Lyons hospital being treated for severe burns sustained when his plane was shot down ten months before, and now, as a prisoner, under the care of the Vichy medical authorities, Flight Lieutenant William Simpson RAF, met the stand-in British charge d’affaires, George Whittinghill of the American Consulate at Lyon – he was temporarily in charge of the affairs of all British people stranded in France, and working to have have Simpson repatriated. It was through Whittinghill that Simpson was introduced to Virginia Hall and through Simpson that Hall was introduced to one of her most valiant supporters, Mme Germaine Guérin, part-owner in a brothel in the city and an ardent enemy of fascism. Guérin had taken a shine to the horribly disfigured Simpson and saw in helping him a means of striking back against the invader and their Vichy lackeys. Simpson was full of admiration for Mme Guérin’s belief that the conqueror’s hubris would soon turn to nemesis if true Frenchmen and women resisted where and when they could. She used the brothel unashamedly to pursue her fight against the enemy:

The brothel was one floor below her apartment, and it was frequented by some of the few German officers and men who were stationed in Lyons and were working on disarmament and wealth-bleeding commissions while I was there. The girls spent many an hour worming secrets out of the Germans, some of whom were terrified at the prospect of being sent from an easy job in France to the horror of the Russian front. Listening to the girls tales was most encouraging to my morale and helped to keep me from losing faith in ultimate victory.

… I respected her fiery love and shame for France and the artistic swagger and carelessness of her courage. She could be ridiculously rash, and yet she could be resourceful in many ways.

[Mme Guérin] taught me more than anyone else how a Frenchman’s heart should beat, and railed for hours with disgust over the treachery and lack of spirit of so many of the young men of her generation… she retained her faith in a typical and illogical way in the ultimate defeat of the Germans and the resurgence of a virile France.

… [Mme Guérin] lived dangerously. She trafficked information to the British, hid British agents, and helped men to escape. Escape was her passion—the escape of the Poles she knew and admired as they passed through Lyons on their way through France and Spain to continue the fight they had been forced to break off, first in Poland and then in France; the escape of Englishmen like myself, who had been left stranded in France or had got away from German P.O.W. camps; and above all the escape of young Frenchmen who wanted to join de Gaulle in England and come back to fight again for France. Scores of British, Polish and French servicemen arrived daily in Lyons and needed to be hidden and helped on their way to the Pyrenees. [Mme Guérin] risked her life to do all she could for them —and it was plenty…

Together these girls shared many things—an appetite for danger, a wicked sense of humour, disdain for their own sensations of fear and the ability to make something out of nothing—to get by, “to scrub around” things. Both had the same love of country, but for [Virginia] it was Maryland. Yet she too loved France—its faults and its qualities—and had the rare ability of inspiring and uniting Frenchmen.

Guérin introduced first Simpson and then Hall to the establishment’s doctor, Dr Jean Rousset. Guérin and Rousset became two of Hall’s devoted and energetic followers, bringing their own personal networks of anti-Petainist and anti-German friends into Heckler’s orbit. Rousset was to become her right-hand man. His code name was Peppin: she just called him Pep, as did almost everyone else. Before long a wide range of supporters – business people, shopkeepers, housewifes, hairdressers, railwaymen, laundrywomen, hoteliers, police officers (including officers in the Sûreté) and prostitutes among others – played various roles in Heckler, gathering information, helping escaping and evading aviators, forging ration and identity cards, finding safe houses and passing messages. Virginia was the maestro who conducted this underground orchestra, her genius for creating relationships, building secret organizations and providing forthright and formidable leadership, serving both to hold the whole thing together, and creating enmities with less capable male colleagues on the way.

The first three agents of SOE’s F Section arrived in France in May 1941, two of whom – the British-educated aristocrat Pierre de Vomécourt (‘Lucas’) and Georges Bégué (‘George Noble’), his pianiste – landed by parachute near Châteauroux in central France.[5] Their orders were simple: to start creating networks of underground groups, men and women who would commit to working together under conditions of absolute secrecy to inform London of the situation across Vichy and Occupied France, and to prepare in due course for liberation.

Bégué made immediate progress, recruiting a number of men in Châteauroux, and Pierre de Vomécourt, establishing a réseau called Autogiro, received his first supply drop in mid-June at his brother Philippe’s (whom he recruited) estate near Limoges. In the same month a Brazilian national, the actress Giliana Balmaceda who was in the pay of SOE, used her neutral status to have a good three-week-long hunt around Lyon, bringing back to Britain a suitcase-full of useful information about life in Vichy France, essential for preparing the new wave of agents – such as Hall – for operations. In August 1941 by Major Jacques Vaillant de Guélis also spent a month collecting every conceivable type of paperwork used in Vichy, for copying in London, as well as recruiting friends to the anti-Vichy cause. He returned to England on September 4, 1941 from a field near Châteauroux, in a Lysander of the RAF’s No. 138 Squadron, newly formed for the purpose of supporting clandestine operations into France, which had brought in an agent – Gerry Morel – on its outbound journey.

Between the first arrival of Bégué in May, and Hall’s arrival in Lyon in November, SOE’s secret operations grew rapidly in both zones. Sixteen agents arrived in September 1941 alone, by parachute and felucca, some of them names of men who were to become legends in the story of SOE: Bloch (‘Draftsman’); Ben Cowburn (‘Benoit’); Victor Gerson, husband of Giliana Balmaceda (‘Vic’); George Langelaan (‘Langdon’), a former correspondent for the New York Times in Paris; the Comte du Puy; and Michael Trotobas (‘Sylvestre’). Operation Corsican, F Section’s first successful supply drop – explosives, weapons and ammunition – took place on October 10, in the Dordogne. But with these numbers and the rapid expansion of brand-new networks and evener greener agents came accompanying weaknesses in security. Arraigned against them in October 1941 were the full forces of the Sûreté, and in a raid on the Villa des Bois, an SOE safe house near Marseilles, a dozen or so of the early agents, including Georges Bégué, were caught and incarcerated. Shortly thereafter, Michael Trotobas was arrested in Châteauroux.

Hall did not fall into the trap, refusing to congregate with other agents, always insisting on staying in the shadows, and of working independently. She got down to business quickly, under a pseudonym she gave herself of ‘Marie’ derived from the first line of introductory code she was instructed to use when meeting the French patriots recruited in Lyon by Jacques de Guélis – Je viens avec des Nouvelles de Marie – although she was happy to use or bastardize any of the others she had been using for various purposes as time went by, including ‘Marie de Lyon’, ‘Brigitte’, ‘Brigitte Le Contre’, ‘Germaine Le Contre’ or ‘Germaine’. To give herself a sense of what was going in on the Reich she read all the German and French newspapers, hunting out snippets of material that she felt would be of use to London. She received and edited material from Mme Bertilon about the political manoeuvrings at the heart of Vichy, especially where they involved the Germans and Italians. She was the point of contact for all new SOE arrivals to southern France. Shortly after her arrival in Lyon, however, her cover as an American journalist suddenly evaporated with Germany’s declaration of war on the United States. To avoid internment, her only solution was to go underground herself, melting anonymously into the city, dropping the use of her real name and using a series of pseudonyms to stay out-of-sight of the Vichy police and Abwehr who, she would have been all too aware, were looking for her. The first place she sought refuge in the city on her arrival was the Sainte Elisabeth convent on the hill high above the Soane just above its juncture with the Rhone: the nuns were to become some of her most faithful supporters in the months that followed, but it was the Grand Nouvel Hôtel near the American consulate in the centre of the city that was to become her headquarters, a useful adjunct to her private apartment. There, her flame-red hair dyed and her clothing style muted to anonymize her amidst a city swollen with scores of thousands of refugees.

That Hall was able to operate far beyond her own instructions among the fast-developing resistance scene in the city she had made her home is evident from a report she co-wrote with Francis Basin – Olive – only a month after her arrival. The report, smuggled to Bern, most likely through the United States’ diplomatic bag to MI6 – it was handed to F Section in London by Commander Kenneth Cohen of MI6 – is a 3-page summary of resistance activities that had been underway since the end of 1940, tracking the efforts of Liberation (at the beginning recruiting in university and military circles, then later principally in leftist circles), Liberté (recruiting in Catholic, democratic and left-centre circles, university circles, syndicalists and trade unionists) and Liberation Nationale, known as "Petites Ailes” after the name of its newspaper, recruiting at the start from military elements, and then among the bourgeoisie of the right and the right-centre. In it Marie and Olive lay out the developing structure of home-grown resistance, observing – long before many others – the initial absence of Gaullism as a unifying force and concluding that an essential condition for effective resistance was agreement and unity with the Gaullists: dissension within dissenting groups would only play into the hands of the Germans.

From the beginning one of the two American vice-consuls, George Whittinghill (the other was Constance Harvey), who worked with Colonel Barnwell Legge, the U.S. Military Attaché in Switzerland, allowed her to use the American diplomatic bag, and it was by this means that her reports to SOE made their way from Lyon to Switzerland, and from there to Washington via Portugal. This route for Hall was a lifeline, as the only other way of getting information to London was via a radio operator, but for much of her time in France they were either non-existent, severely over-worked or too far distant (Châteauroux, for example, was 200 miles way) to be of any use to her. Hall also found that Whittinghill was a man of like mind, who provided considerable help to her from his private resources, not least in order to help escaping British airmen to return to Britain by crossing the Pyrenees to Spain.

Hall ‘was amazingly successful, almost embarrassingly so’ observed Bourne Patterson who wrote the first secret in-house account of SOE operations, ‘since Major Cowburn complained on his return to England from his second mission [in October 1943, after 17-months in France] that one had only to sit for long enough in the kitchen of Marie's flat, to see every British organizer in France. Be this as it may, there is no doubt that without her the progress that was in fact made would have been impossible. She was guide, philosopher and friend to a large number of organizers, helping them with Papers, with Finance, with Advice, with Wireless sets and even on occasions obtaining police uniforms for them and endeavouring to get them out of gaol.’ What Patterson didn’t mention was the central role Hall played in ‘a very great number’ of escapes as a 1944 SOE report put it, including the spectacular jailbreak of Bégué, Trotobus and ten other SOE men from Mauzac Prison in July 1942. Cowburn wasn’t actually complaining about Hall, the opposite in fact. But he was worried about her safety. With so many people dependent upon her for the necessities of life in the zone libre, her security was compromised with every additional connection, no matter how innocent or important. Hall’s success was marked because she was able to achieve much despite the weaknesses and inadequacies of so many of the men who set themselves up in France as agents of rebellion, and yet failed to do much more than massage their own egos. That it was a one-legged woman who achieved near miracles in the painstaking build up of intelligence networks in the zone libre was an irony lost on most of them.

She successfully built relationships with a few trusted Sûreté agents who, though they might not have naturally sided with Britain, nevertheless hated les Boche far more, and worked with those few in the American consulate who were prepared to put their consciences ahead of their careers. At the start of Cowburn’s second mission on June 1, 1942 (he was to complete four), accompanied by the American-born agent Edward Wilkinson (‘Alexandre’) they landed by parachute north-east of Limoges and before long were in Lyon, where, as Cowburn described, Hall ‘was charming and efficient and ready to give every assistance.’

I had a number of things to do in the unoccupied zone for the next few days and I frequently passed through Lyons. I saw a lot of Marie and was very happy to do so. She was paying the price of having a strong, reliable personality: everybody brought their troubles to her, and our HQ in London sent their troubles in the form of agents who were told to contact her to find W/T operators! She was so willing to help that when a needy visitor came she would give her ration cards away, wash clothing and make contacts for him. She had even found out in which jails some of our unfortunate friends were held.

When SOE agent Peter Churchill (‘Michel’) arrived off Cannes in a submarine on January 9, 1942, she introduced him to head of the local ‘Spruce’ réseau, Georges Dubourdin (‘Alain’), a man who was to prove something of a fantasist, and whose desire for a leadership role in SOE was to prove a considerable irritant to Hall. He was a man whose clamouring’s for responsibility were in inverse proportion to his ability to build and lead an effective reseau, but SOE headquarters could not bring itself to believe that a woman could be more effective than a man, and so whatever Dubourdin’s failures he was favoured above Hall, a mere woman. Among Churchill’s tasks was to find suitable landing grounds for the RAF. His instructions for finding Virginia in Lyon were somewhat vague:

All I knew of her was that she was a tall American woman, about thirty-three, who was working as a journalist. At the War Office they couldn’t tell me whether she was dark or fair, but they did say she had an artificial foot, the result of a riding [sic] accident. But this was so cleverly disguised and affected her gait so little that it would be no use as a distinguishing feature. The only way to find out would have been to make her walk on tiptoe! I left a note at her home with the address and telephone number of my hotel, saying that I wanted to see her urgently.

I was lying on my bed when the telephone rang. It was ‘Mademoiselle Germaine Le Contre’. I was delighted to hear her voice, especially when, after I announced that I had news of her ‘sister Suzanne’, she invited me to dinner with her. By now I was sure I was talking to the right person, for her accent was certainly not that of a native Frenchwoman. Shortly afterwards, back in the lobby of the Grand Nouvel Hotel, I was shaking hands with Germaine.[6]

Occasionally in their memoirs the men and women who worked underground in France shock us – decades later – with reminders that none of this was a game. They knew they were in the front line of a desperate – and currently losing – war against a murderous regime and its tremulous Vichy lackey. This wasn’t an ordinary war, perhaps as most Americans back home still viewed it (and many continued to do so, until the holocaust – one terrible part of this new type of warfare – was revealed in its awful reality in 1945), with front lines and armies largely behaving chivalrously within the laws of armed conflict, but a racial war where one side was determined to recreate the world as it believed it should be, in the pattern of an Aryan stereotype. One day in mid-1942 Ben Cowburn was preparing to transport weapons and explosives in two heavy suitcases through Lyon railway station, when he saw a strange train at one of the platforms:

It was formed of large enclosed goods wagons, the sliding doors of which were half open. On the ground opposite each door an armed and helmeted sentry was standing with his rifle. Through the doors could be seen part of the pitiful cargo – Jews apparently, chiefly women and children, trying to press their pale faces into the opening for a breath of air.

A nurse was walking along the 6-foot way with a bucket of water, filling small tin cups and lifting them to the outstretched hands. A prisoner who had fainted was being taken through one of the open doors. Man or woman? I could not see. The poor wretched human being was placed on a stretcher carried by two ambulance men, and as they bore it away, began to vomit.

So it was happening here – this vision of Nazi-dominated eastern Europe was in the main station at Lyons in unoccupied France. The miserable Vichy government had not even thought it necessary to stop the train outside in the marshalling yard. I was filled with rage – I thought of those Sten guns in my bag. I wanted to yell out for half a dozen resolute men to mow down those guards, but a fat lot of good it would have done – the poor wretches would never have been able to get out of the station. I swallowed my rage and resolved to play the worm, as a secret agent so often has to do.

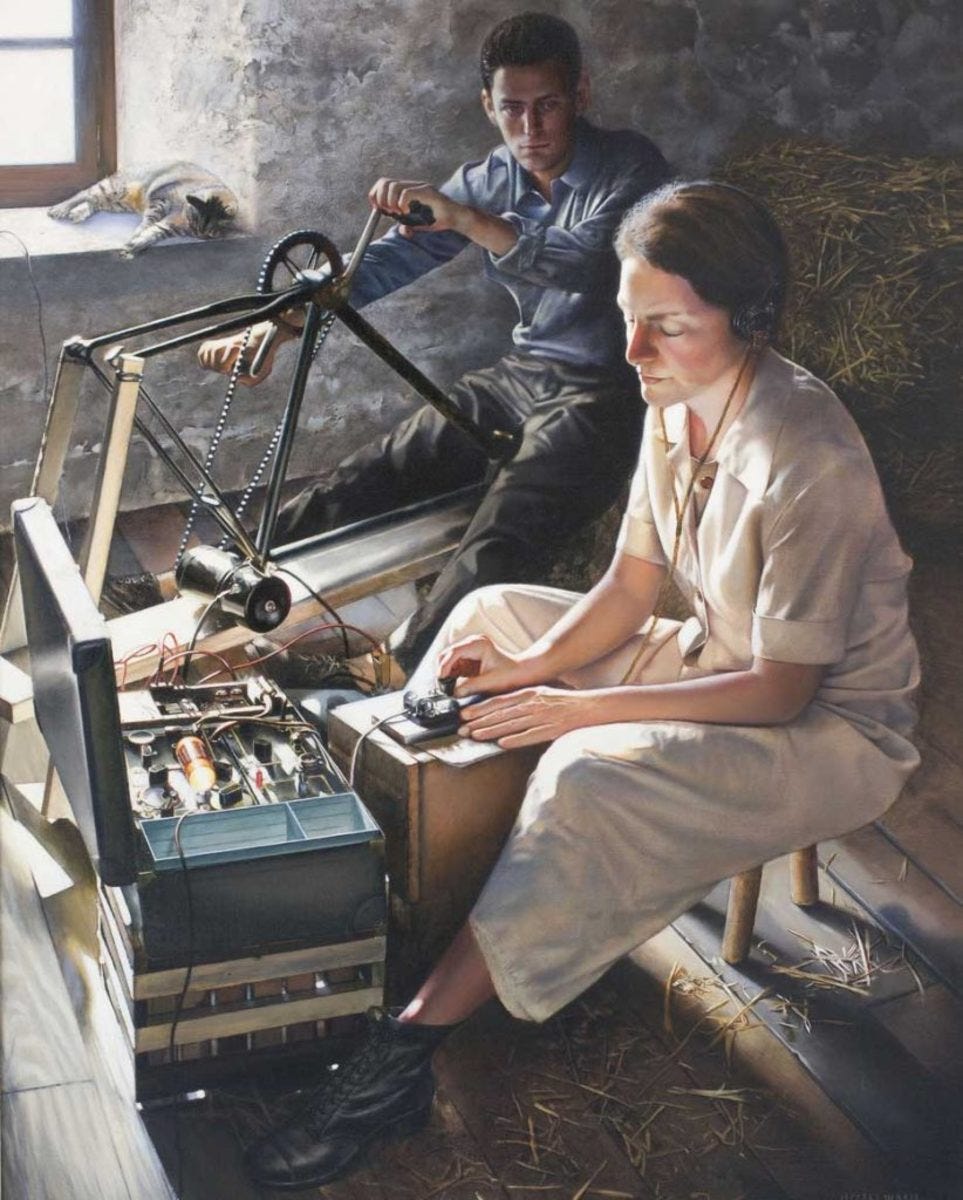

With the arrest of Georges Bégué and the others at Châteauroux, SOE was desperately short of radio operators (‘pianists’ in SOE parlance) and their transmitters. ‘George 35’ the pseudonym of a radio operator (whose real name was Donald Dunton) sent to support Pierre de Vomécourt’s (‘Lucas’) Autogiro network near Paris in January 1942 was landed way off course, near Vaas (in the Sarthe) 22-miles from his destination and after a month of wandering across France (in a journey that took him to Tours, Paris and Perpignan) found himself finally in Marseilles, where Hall was able to made contact with him just as he was trying to arrange his evacuation back to England. She sent him immediately to Châteauroux to collect George Bégué’s hidden transmitter, and set him up to support her and other radio-less réseaux. By this one action alone, concluded Bourne-Patterson, ‘she probably saved the whole set-up in Unoccupied France from premature extinction.’ Radio communication with London, extinguished with Bégué’s arrest five-months before, was re-established. Philippe de Vomécourt’s (‘Gauthier’) ‘Ventriloquist’ réseau was forced to rely on Hall’s radio transmitter in Lyon until he got his own in September 1942.

She wasn’t afraid to provide Buckmaster with advice about the direction each of the SOE reseau was taking, the quality of its leadership and decision-making. In September 1942, for example, Philippe de Vomécourt sent proposals for Hall to forward to London to divide his organization into three autonomous groups with himself as coordinator. Hall was nonplussed, worried about the grandiose nature of the little empires men like de Vomécourt appeared to be creating. ‘Am forwarding plans drawn up by Gauthier and Joseph[7] for the division of Z.N.O. in three districts” she wrote: ‘You might tell them to make less vast plans and concentrate on a little petty but practical work... There is too much stress on grandiloquent plans, too many words and far too little grubbing.’

It was grubbing that Hall did best; lots of it, agents in distress seemingly her specialty. Gérard Morel, a discharged French volunteer with the French Liaison Mission to the British Army now serving with SOE, who had arrived in France on the Lysander that had collected the departing de Guéris, was captured in the devastating round-up at Châteaurox, escaped from hospital in Limoges after an operation on his stomach – entirely unnecessarily, as he had feigned the symptoms, but the surgeon operated anyway – and managed to stagger to Philippe de Vomécourt’s chateau, Bas Soleil at Limousin, twenty-miles north-east of Limoges. On the evening of March 2, 1942, he appeared at her door in Lyon, gave her the current password which was appropriately enough – C’est le docteur qui m’envoie – and was welcomed inside. She hid him and, when he had recovered sufficiently to consider a climb across the Pyrenees, she accompanied him to Toulouse to try to find him a local guide to escort him across the mountains. She had enough contacts by this stage to successfully engage a passeur, but the process of organizing each trip was ad hoc, an experience that reinforced in her mind the need to establish more formal, organized routes across the mountains to Spain. One, the famous Pat O’Leary Line, had been going since 1940, but this was primarily for escapers and evaders, and she needed one for secret agents. It wasn’t until later in 1942 that SOE agent Victor Gerson (‘Vic’) was able to build a remarkable escape line, helped particularly by Spanish Republicans, that ran between Perpignan and Barcelona, and was never broken. Until then escaping agents were forced to follow their noses. Without someone – like Hall – in the region to facilitate, the task was nigh on impossible. This was Cowburn’s experience in March 1942 when he failed to make a rendezvous with a boat that was to have taken him home across the English Channel. Cowburn had first parachuted into occupied France on September 6, 1941 with Pierre de Vomécourt. An oil engineer who had spent much of his life in France, his mission was to obtain information on the best targets for the sabotage of oil and fuel stocks.

In Lyons I went in search of someone that [Philippe de Vomécourt] had mentioned, and was delighted to meet this tall, blonde young American, very charming and obviously very capable, who answered to the code name ‘Marie’. She told me how to get in touch with an escape line based in Marseilles. She also introduced me to a man called Joseph, a member of the same group, who very hospitably offered me the use of his flat; I was thus able to enjoy the luxury of a hot bath, pyjamas and a comfortable bed.

I went to Marseilles the following evening and found my way to a bar called Le Petit Poucet. I had a bit of trouble persuading the manager that he could trust me. But my story and the name of the person who had sent me finally convinced him, and he agreed to introduce me to a certain gentleman. The latter, too, was very wary at first; but he took me to his home and after a long conversation I managed to reassure him that I wasn’t a police spy. Fortunately, prior to the war I had often been in this area on business, and I was able to describe several mutual acquaintances, which removed his last remaining doubts. The attitude of this man and his wife, as well as all the precautions they took in their work, showed me that this organization really meant business. They offered to put me up for the night, and the following morning, along with several other ‘clients’, I caught the train for Toulouse – the first stage of our journey.

Cowburn successfully got out of France, but mainly because of luck. Some agents needed more help than others. Denis Rake, whose colourful story of life as an SOE agent is described in his memoirs, began operating as a pianiste for the Spruce réseau after landing from a felucca at Juan-les-Pins in May 1942. The instructions he received for meeting Hall were to look for someone reading a copy of the Journal de Geneve, but she wasn’t difficult to spot he recalled, as she was ‘a very striking woman who once you had seen you would never forget, for she had red hair and an artificial foot’.[8] Warned that the French police were onto him, he decided to hide in Paris, so Hall gave him the photograph of a fellow SOE agent, American-born Edward Wilkinson, who had landed with fellow-agent Ben Cowburn but without a radio on June 1, 1942. Hall arranged to send his transmitters separately. The French police caught him crossing the Demarcation Line, however, although he managed to escape by bribing his guards with virtually all the SOE funds he had on him to jump from the train. He headed on to Paris but although meeting with Wilkinson, could not find his transmitter, so he returned to Virginia in Hall in Lyon, this time with another SOE agent – Roger Heslop – in tow. Heslop (‘Xavier’) recounts being introduced to Hall in her ‘gloomy flat’ in Lyon by one of Philippe de Vomécourt’s men:

The door was opened by a girl, who looked at me with suspicion, but at a nod from Jacques, she showed us in, and there was Wilkinson [‘Alexandre’], the pipe-smoking, hawk-eyed, slim man who was my friend. ‘Hello, how are you? You don’t look too happy,’ he said.

‘Hello – it’s good to see you. Very good to see you. ’

He introduced me to the girl, Mary — a very brave American girl — and they carried on with their conversation. ‘Don’t forget Cuthbert, it may not be all that easy if you forget him,’ she was saying. Two or three times in as many minutes the name of Cuthbert (who seemed to be a real fly in the ointment) cropped up, and I could stand it no longer. ‘Who’s this damn man Cuthbert? ’I asked.

Mary simply banged one of her legs against the table, and it gave out a hollow sound. “That’s Cuthbert,’ she said. ‘He’s wooden.’

Now, Hall was insistent that Rake now return home via the Pyrenees, his cover now having being comprehensively blown. But advice was all she could proffer: agents were largely responsible for their own decisions, and the flamboyant Rake decided to travel back with Heslop and Wilkinson (‘Alexandre’) to Paris, this time with Wilkinson carrying a precious transmitter in his luggage. This time all three of them were caught by the French police at Limoges.

Unaware of the arrest of the three men, Cowburn had a collected a small parcel addressed for Hall from a canister that had been dropped by parachute, so at the first opportunity he returned to Lyon to give it to her:

When she opened the door in answer to my ring, she exclaimed: ‘Thank God! You are a sight for sore eyes!’

She ushered me in and said she had been afraid I had also been arrested.

‘Why also? Who has been arrested?’

‘Alexandre...

‘What? Alexandre?’

‘Yes, and the two others ...’

A few days after the trio had left for Limoges and Paris, one of her remarkable grapevines had informed her that three British officers had just been arrested in an hotel in Limoges. She had gone there and managed to get some information. Her story was, roughly, as follows. The operator [Rake], who had not yet recovered from his recent shock, had had the misfortune to make a slight error in behaviour when, by sheer bad luck, a couple of police inspectors entered the hotel for a snap check. His anxiety did not pass unnoticed. He had been detained and, when Alexandre and the third man came to join him, they had walked into a trap. The discovery of the W/T transmitter in the luggage had put the lid on it and all three were in jail. Both Marie and I were stricken with grief at the thought that they should have been taken and especially after so short a time in the field.

Unknown, of course, to either Cowburn or Hall was that Heslop was so incensed by the affair that he was convinced that Rake was a Vichy or German agent, and had shopped them to the Vichy authorities. This wasn’t the case, but Rake’s behaviour – nervousness at best and an incautious attitude to security at worst –had clearly resulted in their arrest. Despite orders for their execution the men were released by their prison guards on the eve of the German occupation of the zone libre in November, and Rake managed to cross the Pyrenees to safety in the company of other escapees. Heslop and Wilkinson, disowning a man they considered a turncoat, returned to Paris.[9] Rake was safely back in London by May 1943: he never forgot the selfless help Hall had provided to him. Virginia’s account of the arrest of the three men, sent to London in September 30, 1942, reads like fiction, but was full of practical advice for London. When Rake had fallen under suspicion at the hotel in Limoges, he was discovered to have several thousand francs (all beautifully forged in London) in his wallet, all new and in sequential numbers. Notably, the high denomination notes had not been pinned in the top left-hand corner, as was French central bank practice, a detail unknown to the forgers in London. When Heslop and Wilkinson came to find the hapless Rake, they were also arrested and found to have the same incriminating currency.

As 1942 neared its end, Vichy and German penetration of the rather flimsy security with which she had surrounded herself became inevitable. The time was fast emerging when she would either be arrested, or forced to escape for her life. Many of her friends had been caught and their networks dissolved – including Pierre de Vomécourt and his autogiro réseau – in a sea of arrests, torture, execution and deportation to an anonymous Konzentrationslager in the Reich as part of the Nazi ‘disappearance’ – nacht und nebel – scheme. The closest her protection came to unravelling seemed to be when the Abwehr in Paris sent a false prophet – the priest Abbé Robert Alesh – into her Heckler réseau in Lyon. It was a classic trick, and so often worked: the agent provocateur sent to infiltrate an organization by pretending to be a fervent disciple of the cause, usually dangling some juicy falsehood with which to trap the unwary, only to hand the whole organization over to the enemy when the entire extent of the network – leaders, workers and their families alike – could be identified, listed and exterminated. The only real way to avoid such an eventuality was to operate alone, or in hermetically sealed groups that did not rely for sustenance on anyone or anything on the outside, and refused to deal with anyone they could not personally vouch for. But Virginia Hall, by the very nature of her role in Lyon, was in no position to fully protect herself from this sort of infiltration. All she could do was to be suspicious of everyone. It saved her life. When Alesh arrived at the home of her key lieutenant, the too-trustful Dr Jean Rousset, she was doubtful of his credentials, although every check she was able to make suggested that he was genuine. He purported to be from a réseau in Paris – Gloria – and had important naval secrets to get to London. She fobbed him off, however, and he went elsewhere, quickly and devastatingly dismantling another group that was taken in by the smooth-talking priest in the pay of the Germans, who had in fact infiltrated Gloria and taken it down. On September 21, 1942, Hall saw the enemy closing in, sending a message to SOE: “My address has been given to Vichy . . . I may be watched . . . my time is about up.”[10]

But she survived another six weeks. The catalyst for her departure from Lyon on the late night train from Lyon to Toulouse and thence Perpignan on November 11 was a nod from a friend she had cultivated in the Deuxième Bureau, who tipped her off that the Germans were about to move into the zone libre following the Allied landings in North Africa, and had been asking questions about a female agent in Lyon, probably Canadian or English. No one seemed to have connected Virginia Hall, the accredited journalist for the New York Post with Germaine, Marie, or any number of the alias’s with which she had successfully camouflaged herself. The man who had been appointed to lead the Gestapo in Lyon, Klaus Barbe, was reputed to have said that he would do anything to get ‘his hands on that Canadian bitch’.[11] But she already knew that her time was up, as her close friend, confidant and fellow-architect of the SOE empire in Lyon, the redoubtable Dr Jean Rousset, had been arrested three days before. She knew that the Abwehr and others had been working for months to get her. Lifelike ‘wanted’ posters of her could be found across France, describing her as ‘The enemy’s most dangerous spy.’ In her heart of hearts, Hall knew that she was next.[12] She fled.

The story of her climb over the snow-covered Pyrenees in late November 1942 is one of extraordinary heroism and determination. That she did it at all was a considerable physical achievement: doing so with a false leg (which she didn’t let on to her Spanish guide, who had agreed to take her and two companions for 55,000 francs of SOE cash) in winter was testimony to her physical toughness and mental courage. ‘God knows how she made the journey over the mountains,’ exclaimed Philippe de Vomécourt when he heard of it in 1944. The path, covered with snow and ice, would be have been unbearable for anyone with two legs: for Hall, the agony of her stump on her left leg, tender and suppurating, was a trial that few ordinary mortals could have coped. Craig Gralley, who in 2016 found and walked Hall’s long-lost route following a path from the village of Py, close to the walled medieval city of Villefranche-de-Conflent, up into the hills, skirting the 6,000-foot Pic de lay Donya, towards the Spanish border, three days walk away, noted that even Hall admitted that crossing the Pyrenees was “the scariest part of my life overseas.”

After three hard days of walking, which included negotiating mountain passes over 7,500 feet, she contacted SOE from the Spanish side of the mountain with a radio left in a safe house by a previous escaper to announce that she had crossed safely. Her stump had been rubbed raw, however, and her wooden and aluminium leg needed urgent repair. 'Cuthbert is giving me trouble’ she said, expecting the receiver to pass the message on to Boddington, who would understand the coded language. In what is now a legendary response the SOE handler responded immediately: ‘If Cuthbert is giving you trouble, have him eliminated.’ She would have laughed at this, as would Boddington when he received the message. Hall was back in London, after more adventures in Spain, by Christmas.

The new head of F Section, Maurice Buckmaster was in awe of what Hall had achieved, along with all in SOE who knew of her activities. In June 1945, two-and-a-half years after she left SOE’s employ, he wrote a citation proposing Virginia Hall for a George Medal, the highest British civilian award for bravery, summarizing her importance to the early life of SOE in France:

Virginia Hall is a commanding figure in the early history of SOE – a resourceful and brilliant agent playing a key role in helping numerous other agents establish themselves and make vital contacts. Almost all the early agents who went to France had dealings with her – a procedure in itself completely at variance with SOE’s tight security procedures. This was no lapse but was possible thanks to Virginia’s unusual cover. She was an American citizen, using the cover of a journalist working for the New York Post, accredited to the Vichy authorities.

She has been indefatigable in her constant support and assistance for our agents, combining a high degree of organising ability with a clear-sighted appreciation of our needs. She has become a vital link between ourselves and the various operational groups in the field, and her services for us cannot be too highly praised.

It was denied. She had already received the lowest award available, the MBE, despite being proposed for a CBE, and in what seems a gratuitous and embarrassing example of official parsimony it was considered that Hall had received sufficient reward. But she couldn’t care less. Within weeks she was badgering anyone who took an interest to be allowed to return to France.

Further Reading

There are a series of rather indifferent and not always accurate chapters and books on Hall. They are best left alone: some contain egregious errors of fact, the result of being written long before either the British SOE files in Britain’s National Archives or the American OSS files in NARA, Maryland were available to historians. The three best books are, in order of publication date, Vincent Nouville’s L’espionne: Virginia Hall, une Americaine dans la guerre (2007); Sonia Purnell’s A Woman of No Importance (2018) and Craig Gralley’s Hall of Mirrors (2018). Craig Gralley’s account of finding and walking Hall’s route out of France is in Craig R. Gralley, A Climb to Freedom: A Personal Journey in Virginia Hall’s Steps is in Studies in Intelligence Vol 61, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2017). William Simpson’s story is told in I Burned My Fingers (London; Putnam & Sons; 1955).

[1] Allan Mitchell Nazi Paris: The History of an Occupation 1940-1944 (Berghahn Books, 2008)

[2] IWM interview, 1986, 9331.

[3] The National Archives HS9/647/4, letter of Virginia Hall, 25 Nov. 1941. The original contains an incorrect year, 1942, which the contents of the letter demonstrate to be an error. The message confirms that at least Boddington was aware of her false left leg. It is possible that he keep this a secret even within SOE.

[4] MRD Foot

[5] Bégué was code-named ‘George Noble’. All SOE radio-operators, or pianistes, were subsequently code-named George.

[6] Peter Churchill, Of Their Own Choice (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1952). Dubourdin was later captured and sent to Buchenwald, where he was executed in April, 1945.

[7] A local recruit, Jean Aron, who worked in the Ventriloquist réseau.

[8] Denis Rake, Rakes Progress (Leslie Frewin, 1968), p. 104.

[9] See Denis Rake, Rake's Progress: The Gay and Dramatic Adventures of Major Denis Rake, MC (Frewin, 1968) and Geoffrey Elliott The Shooting Star: The Colourful Life and Times of Denis Rake, MC (Methuen, 2009).

[10] Blind message from Philomene (Hall’s code name), 21 September 1942. The National Archives: HS9/647/4 703284.

[11] MRD Foot

[12] Rousset was sent to Buchenwald, which he survived.