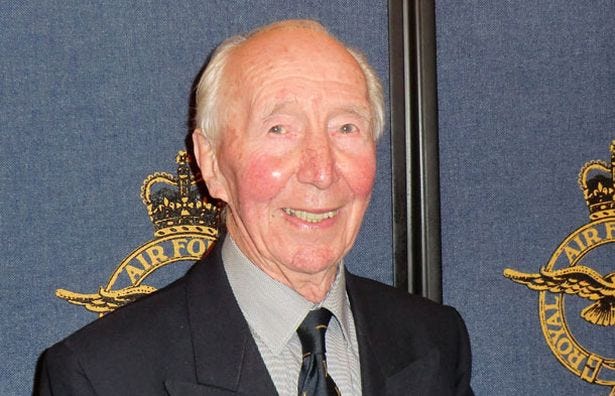

One of the many Burma veterans I interviewed over the years was the late Ray Jackson MC. His story was extraordinary.

On the afternoon of 22nd March 1944 soon after the start of the great struggle for Imphal, Jackson took off from Palel on the Imphal Plain in a 34 Squadron Hurricane IIC on a bombing and strafing mission against the village of Kuki, over the border in Burma. During the attack, however, his aircraft was hit by ground fire and rapidly began losing oil. Knowing that he would have to bail out he pulled back the stick to gain height. At 1,500 feet his engine stopped and caught fire. Flipping his aircraft onto its back Jackson fell, but knocked himself out in the process and lost most of his precious emergency rations, which had been stored in a pocket that ripped as he fell. Fortunately, when he came to he found himself floating under his parachute, watching his aircraft far below hit the ground. He landed on a scrubby hillside, but his descent had been observed and within minutes he could hear the sounds of men making their way in his direction. Hastily scrambling up the hill towards denser jungle Jackson managed to elude his pursuers, even after they had started a series of bush fires on the slopes below where in an attempt to flush him out. Hiding in a patch of jungle he could, at one stage, have reached out and touched two of his Japanese hunters.

With him he had a .38 revolver, knife, machete, map and a few survival rations including a canvas water chargul. Calculating his position and determining his direction of march by the sun he decided to make his way across the hills northwest to the Naga village of Jessami, thinking that he would reach it in two or three days. But the terrain was far more difficult to cross than he had expected and after twelve days of struggling up the steep jungle covered hills and down again into deep valleys, crossing the streams that ran through them, he had not yet reached safety. Growing progressively weaker he narrowly avoided capture after stumbling into a Naga village occupied by Japanese troops. All about him were signs of considerable Japanese activity, the paths covered in their distinctive cloven-footprints. He survived on a dried melon and some grains of corn that he picked up after coming across abandoned fields, together with salt tablets from his emergency rations. Exhausted, attacked by mosquitoes, leeches and ticks he was on one occasion charged in failing light by a panther, which at the last moment veered off into the jungle, leaving him alone, and surprised at his escape. Looking down, he was astonished to find that he had his revolver in his right hand. ‘I had no recollection of doing it’ he said later, ‘but it must have been one of the fastest draws ever made in the RAF.’

On the twelfth day of these exertions Jackson came across a Naga village unoccupied by Japanese. Dazed with exhaustion, he collapsed on a path leading up to the village:

I had lain there a short time when I heard a scream and saw a Naga woman running down the path to the nullah. After a few minutes two Nagas with spears came up the path. They were followed by four women bearing baskets on their backs. I smiled and tried to look friendly and saw signs of relief pass over their faces. A young woman smiled at me. I then made signs that I needed food and drink. They all smiled and produced a calabash full of a liquid that tasted like a sour white wine with a sherbet added. I managed to swallow some of this and it seemed to pull me round a little. They then gave me some rice containing some berries that looked like blackcurrants.

Fed and sheltered by the villagers, Jackson then learned that he was still two days’ walk from Jessami. Leaving the next day he made his way along the tracks towards the village, which he skirted to the east because of sounds of gun fire around the town. Coming across a further village to the north of Jessami – equipped ominously with skulls on bamboo poles at its entrance – he was well treated and fed. On the following day, attempting to travel west he rounded a bend on a track and encountered two young men, each one carrying half a bleeding pig on his back. He had stumbled into the outskirts of the village of Phekakedzumi, 30 miles east of Kohima. ‘You British?’ one of them enquired quickly. A nod from Jackson had them hustling him quickly back in the direction he had come, away from the village, which housed a substantial Japanese garrison. One of the men – Vepopa – recalled the moment he first saw the tired Jackson:

One evening as I was coming back from the Japanese camp, I met a person but as soon as I saw him, I knew he was not a local person. I could not speak English or Nagamese or Hindi so through sign gestures, I asked, ‘What happened to you?’ He replied in signs that his aeroplane had crashed and he pointed toward Jessami. I realized that he had been saved by God’s grace and took him away because he was very close to the Japanese camp. I took him to Phek Basa [huts in the fields to where the villagers had decamped when the Japanese occupied the village]. He was so weak that I could almost see his bones. He also had dysentery and had bruises on his face. I knew that he would not gain strength if he did not eat good food so I fed him with chicken, pork and fish as well as sugar and milk which were difficult to procure at that time.

The other man – Susai Hoshi (25) – was a local Christian pastor. He and his wife bathed Jackson’s feet and treated his wounds. When they found out that he was a Christian too, they sang hymns for him. ‘I was reminded of the Bible story of Jesus having his feet bathed. The tenderness and care with which they treated me moved me very deeply.’ Hoshi and Vepopa now had the problem of how to guide Jackson to safety. Vepopa recalled:

As I spoke no Hindustani or English, we talked through sign language and later, my brother, Vechotsu acted as my interpreter. Because the Japanese were at the old Phek village so close to us, I sent him on his way with some escorts, on toward Sohomi. A brother of mine who was settled there took care of him and took him to Vesoba village.

Disguised as a Naga, clothed in a blanket and carrying a spear, Jackson made his way westward through the hills accompanied by a phalanx of six Naga guides, similarly dressed. They looked like a typical Naga foraging party and successfully evaded the ubiquitous Japanese patrols in the area. Several days later the little group finally met with a patrol first from V Force and then from a Chindit column. The V Force group was commanded by a British Army Major, and all ‘bristled with grenades, sten guns and knives.’ On 22nd April, exactly a month to the day since he had bailed out, a gaunt and heavily bearded Jackson arrived unannounced at his squadron. The surprised greeting he received by the first man he met, after long being presumed dead, was ‘**** me, it’s Mr Jackson!

Ray Jackson was one of the loveliest men I have ever met. One of his final requests was to give the Kohima Educational Trust a considerable amount of money to build a basketball court at the village of Phek, a project the villagers had asked for, in tribute to the treatment he had received so selflessly by them in 1944.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful story Rob. Ray's exploits are inspiring but it is the generosity and warmth of the Naga's that helped him that really shine through.

Amazing. Humbling.