The Defence of Outpost Eerie

One night in a long (Korean) war

Exciting news! If I haven’t yet told you, on 22 May 2025 General Lord Dannatt’s and my new book on Korea will be published. You can reserve your copy here.

Historians and commentators on war often ignore the small engagements in campaign and wars because they don’t seem to amount to much. But this is a mistake. It is often in the execution of battle - even small engagements - that wars are won and lost, strategy is made and unmade.

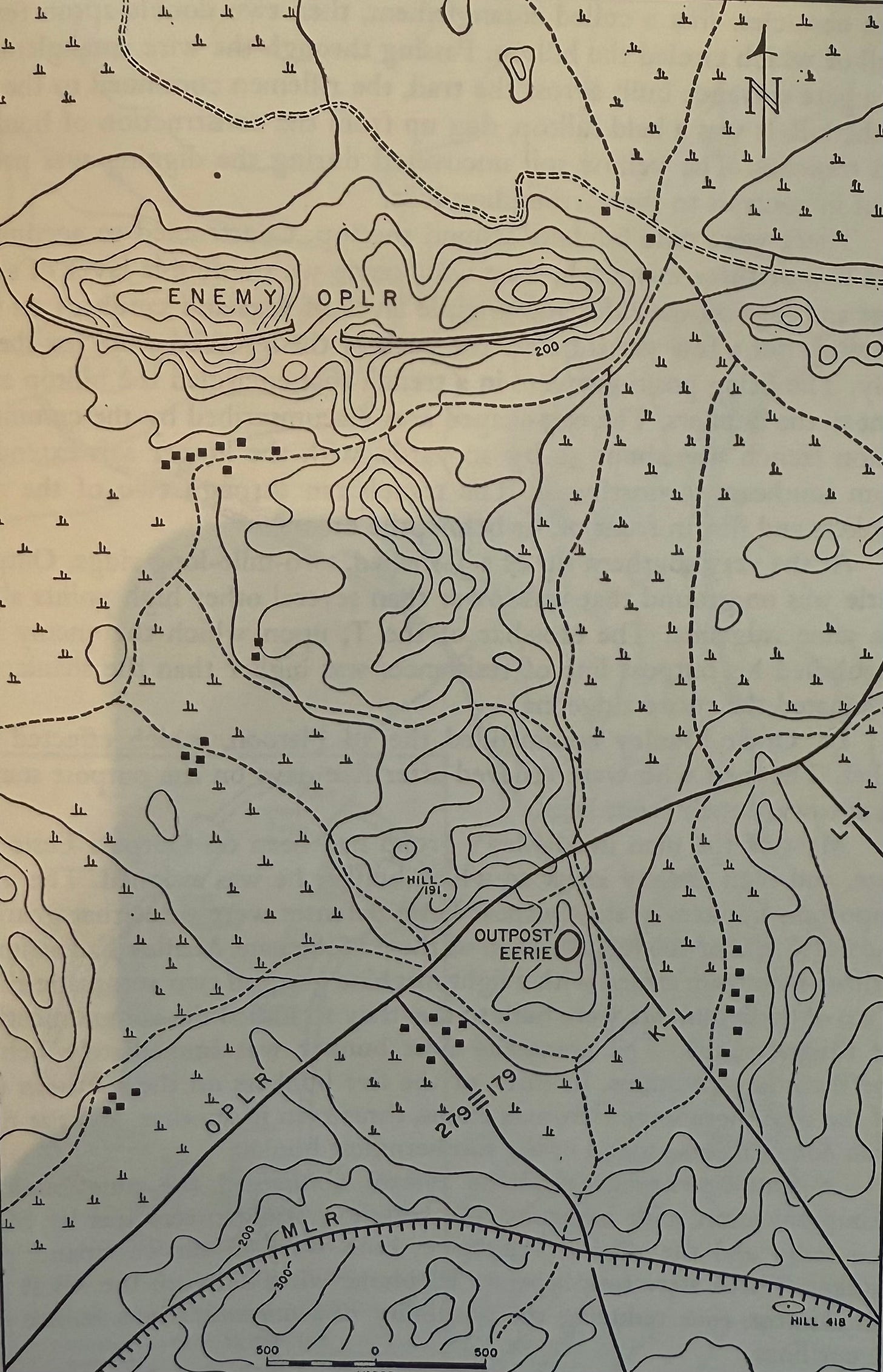

One of the features of the Korean War, at least in its second phase - the two years from July 1951 through to July 1953 - was that it was a war of many small engagements along what was called the Main Line of Resistance, a defensive line roughly approximating the 38th Parallel which separated North from South Korea. The platoon action by men of 179th Infantry Regiment at Outpost Erie in March 1952 was one of many thousands of such actions that characterised this new stage of the war. It is remembered to history because Russell Gugeler included it in his excellent compilation of representative combat actions in 1954 for the U.S. Army Historical Series. I thought I’d recount its essential detail for you here.

On the night of 21st March 1952 twenty-six men of 3 Platoon, Company K, 179th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Omer Manley, trudged out in single file to occupy a bald pimple a mile north of the Main Line of Resistance ten miles west of Chorwon. It was one of hundreds of separate actions being undertaken that day and every day along the Main Line of Resistance. It was part of the routine tedium of retaining an offensive spirit while maintaining a static defensive position over a long period of time. The pimple was Outpost Eerie, a patrol base designed to serve as a permanent listening patrol to provide warning in front of the 179th Infantry’s positions of an impending Chinese attack, as well as to mount patrols against the Chinese line of resistance, which lay a mile and a half to the north. Outpost Eerie occupied the northern end of a long ridge sitting about 120 feet above the padi fields below. The position included nine inter-locking bunkers providing all-round defence of the position, wrapped about with three separate layers of barbed wire. The platoon would stay there for five-days before being replaced. The platoon comprised four groups of men who would occupy the two and three-man bunkers: two rifle sections, a 60mm mortar section of five men; and a light machine gun section of three men equipped with .30 calibre machine gun. Forward of all but two of the bunkers – which were designed for sleeping only – was a fire or communication trench that ran around the full extent of the position. It was from this that the men would fight, if necessary, for the defence of the outpost. The platoon Command Post (C.P.) bunker with three men – Manley and two others – was connected to the Company K positions back on the MLR by radio and telephone line. It was from here that artillery and mortar support would come in case it was required. Each bunker was connected by an internal telephone system. A sound-powered telephone system connected the nine bunkers.

Unknown to Lieutenant Manley and his men that same night a Chinese company commander from the positions to the north began preparing sixty of his own men for a raid on Outpost Eerie. Their task was to attack the position and capture two prisoners.

The battle for Outpost Eerie that night would reflect one of many thousands of similar platoon level actions that defined this period of trench warfare.

On taking over the position that rainy afternoon Lieutenant Manley allocated his troops to their firing positions. The three northern most northern bunkers were allocated to the light machine gun section on the left, and two other bunkers, each with three-men. Not unreasonably Lieutenant Manley wanted to place his firepower at the most vulnerable spot and where it could do the most damage to an attacker, assuming that he came from the north. His own platoon C.P. was immediately to the rear of these forward bunkers. To the rear, the south-eastern five-man bunker was occupied by the platoon’s 60mm mortar section. The remaining four bunkers held two or three men armed with Browning Automatic Rifles and M1 semi-automatic carbines.

In addition to the twenty-six men on Eerie that night, the battalion deployed two separate patrols, taking up ambush positions to the west and east of Outpost Eerie. These were designed to further protect the outpost from a surprise attack. Both left Eerie that night at 7 p.m. The first patrol was to occupy an ambush position on the track six hundred yards to the north while the second patrol comprised nine-men who were to occupy Hill 191 about six hundred yards to the north west. The Hill 191 patrol was to return to Eerie about 2 a.m. while the ambush patrol was due to return directly to the M.L.R. at the same time.

The rain stopped by 8 p.m. but it was cold and misty. This was an active area of the front and Lieutenant Manley and his men fully expected some action. The first sign of enemy activity was a report from the Hill 191 patrol at 11 p.m. that a party of six Chinese had been spotted a hundred yards to their front setting up a machine gun. About the same time the ambush party on the track to the north reported a platoon of enemy heading south, at a distance of about 150 yards. They opened fire in the darkness but the enemy appeared to ignore the firing and kept going. Lieutenant Manley immediately reported this to his Company commander on the M.L.R. ‘The patrol has broken contact and is withdrawing to the M.L.R.’ he told him. ‘We're cocked and primed and ready for anything.’

Fifteen minutes the troops on Eerie, tensed for action, heard sounds in front of forward bunkers but no one could determine whether these were from the returning patrol or the Chinese. A few minutes after this, at 11.30 p.m., two trip flares went off beyond the barbed wire to the front of the position. An attack was imminent. Sergeant Calvin Jones and the other men at the northern end of the outpost opened fire with automatic weapons and small arms. Chinese voices could now be clearly heard beyond the wire.

At this point two enemy machine guns began spraying the positions from the north east and north west. At least one of these had been spotted by the patrol on Hill 191. Grazing fire fell across the entire Eerie position. Corporal Nick Masiello, commanding the .30 calibre machine gun, alternated his bursts between these weapons and the Chinese who were attempting to breach the wire below him. The enemy gunners replied by concentrating fire on Masiello's gun. Meanwhile, on receiving the report from Lieutenant Manley his Company Commander on Hill 418 to the rear, Captain Clark, began to provide depth fire to support the defenders of Eerie, using his company mortars and a .50-calibre machine gun on Hill 418. Clark could see the machine gun duel lighting up the sky in a bright technicolour display to his front. When the mortar shells began landing around the position Lieutenant Manley telephoned the necessary adjustments back to Captain Clark.

‘They're giving us a hell of a battle out here, but we're O.K. so far’ Manley reported. ‘Bring the mortars in closer. No, that's too close! Now, leave them right where they are.’

Chinese machine guns rounds were now ripping through the unprotected shelter covers over the bunkers, forcing Manley and the forward defenders to crouch down in the firing trench. It was from here he realised that the battle for Outpost Eerie would have to be fought.

Fifteen minutes after the Chinese covering fire bagna, blanketing the position, a burst from one of the enemy heavy machine guns hit and killed Corporal Nick Masiello. His crewmen got the machine gun going again. A battle of machine guns continued for the next forty-five minutes. Lieutenant Manley attempted to remove one of them on the Hill 191 ridge by calling in artillery fire on the Chinese positions, though it was impossible in the dark to get an accurate fix on the enemy machine gun. During a telephone report at half past midnight Private Winans, the platoon runner, reported to Captain Clark: ‘Everything's OK, sir; they're not through the wire yet.’

Winan’s assumption that this was what the Chinese were doing was correct. Two enemy assault groups were, under cover of their supporting machine gun fire, attempting to blow gaps in the circle of protective wire around the position. The only counter Manley could deploy, so close to his position, was artillery fire which he called in repeatedly. Attempts to provide illumination rounds from a supporting 155 mm artillery battery failed, most of the shells inexplicably bursting too close to the ground to provide effective light.

Meanwhile, Chinese machine gun fire wounded Private Robert Fiscus, a Browning Automatic Rifleman in the northernmost bunker. Almost immediately afterwards Private Hugh Menzies was wounded by grenade fragments.

It was at about 1 a.m. that it became apparent that the enemy had succeeded in breaching the wire in two places. Lieutenant Manley yelled to his men, ‘Get up and fight or we'll be wiped out! This isn't any movie!’ Chinese assault parties were now crawling up onto the position, throwing grenades as they went, not standing up to present themselves as easy targets. The 3 Platoon medic, who until then had been doing sterling work on others, was hit in both legs by burp-gun fire, and in the arm and head by shell fragments. Of the nine men initially occupying the three bunkers facing the enemy attack only five remained unharmed.

The struggle for Eerie now became one of individual life and death. BARs and rifles were fired until ammunition was exhausted. Corporal Godwin, who had moved up into the centre bunker from the C.P., realising that there were no more grenades, picked up a rifle and began firing into the advancing Chinese from a position in the fire trench until his ammunition was gone, before throwing his rifle at the nearest Chinese. He saw the butt hit the man in the face, knocking him back down the hill.

The time was now about 1.15 a.m. The machine gun trench was under direct assault. Soon after, Godwin’s position was also attacked; Chinese troops were spotted on the roof. It was now a fight between man and man.

Corporal Godwin spotted a Chinese soldier coming along the trench toward him. He stepped back against the bunker, waited until the Chinese was within point-blank range, and shot him in the head with his pistol. An enemy soldier standing on the edge of the trench fired a burst at him from his burp gun, but then moved on without determining whether he had hit Godwin, doing no more harm that denting his helmet. Moments later an enemy soldier threw a concussion grenade at him and knocked him unconscious.

While this assault was taking place the Chinese were making a simultaneous breach from the west. Sergeant Kenneth Ehlers, who was the section commander (‘squad leader’) for the four rear left bunkers was joined in his trench area by Lieutenant Manley, Corporal Robert Hill and Corporal Joel Ybarra, fighting off the incursion with their automatic rifles, M1 rifles, and grenades. Both Ehlers and Hill were killed. At a critical moment Lieutenant Manley ran out of ammunition for his carbine, so he threw it at the Chinese and then started throwing grenades at them. After only a few moments, however, all resistance from this side ended; the platoon leader and Corporal Ybarra disappeared. At about the same time a shell destroyed the C.P. bunkers, killing its remaining occupants.

The three remaining bunkers in the south west of the perimeter continued to hold, despite it being obvious to them that the Chinese had occupied the centre of the Outpost in force and that the forward bunker positions had fallen. The time was about 1.20 a.m. Realising that this must be the situation, having not heard from the C.P. or Lieutenant Manley for some time, back on Hill 418 Captain Clark ordered his artillery to fire a Final Defensive Fire onto the top of the Outpost Eerie position. In a few minutes, 105 mm rounds began bursting over the position. There followed the sound of a horn blown three times, and within a few minutes enemy activity ceased and firing died down. The Chinese now withdrew from the shattered position. At 2 a.m. Captain Clark had gathered his company together on the M.L.R. and began moving out to relieve the the outpost. On the way they met the ambush patrol, all members of which were safe. The patrol had been caught in the open when the fighting commenced and had been unable to take an effective part in the action. Company K reached Eerie at 4 a.m., about two hours after leaving the main line. After an hour's search, Captain Clark had accounted for all men except Lieutenant Manley and Corporal Ybarra, both of whom had disappeared from the same bunker.

Of the twenty-six men who had defended Outpost Eerie, 8 were dead, 4 wounded, and 2 were missing in action, a casualty rate of more than fifty per cent. Captain Clark considered that it was the final artillery fire which fell on the outpost that had prevented further casualties and forced the Chinese to withdraw. They had, after all, achieved their objective, dragging Lieutenant Manley and Corporal Ybarra with them into a captivity that would end over a year later with the armistice.

A single night’s platoon action on a remote and isolated hill forward of the M.L.R. accounted for the expenditure of 2,614 rounds of artillery ammunition. In addition the regimental Mortar Company and the 3rd Battalion's heavy weapons company fired 914 mortar shells. The bodies of 31 enemy dead were recovered, and a wounded prisoner taken captive.

It was in this manner that the war raged along the M.L.R., day after day, night after night during the long period of static warfare between mid 1951 and the armistice in July 1953. By such means was the war won, for by it the U.N. plan (admittedly not the one it had started with) to draw the war to a close (a) with without escalation to a nuclear level and (b) without the forced unification of both Koreas under Pyongyang, was successfully achieved.

“By such means was the war won…”

Was it? Armistice still exists.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Armistice_Agreement

Very interesting, thanks. I'm not familiar with the Korean war, but I'd assume the static war for 2 years was due to the overwhelming people superiority of the Chinese forces?