The Burma Campaign as an imperial (and coalition) triumph

Some thoughts from my recent trip to Nagaland and Assam

I’ve just returned from a two-week visit to Nagaland and Assam with a group curated by Bertie Lawson of Sampan Travel. We spent much time discussing the essential characteristics of the Burma Campaign, one of which was the polyglot nature of its fighting forces.

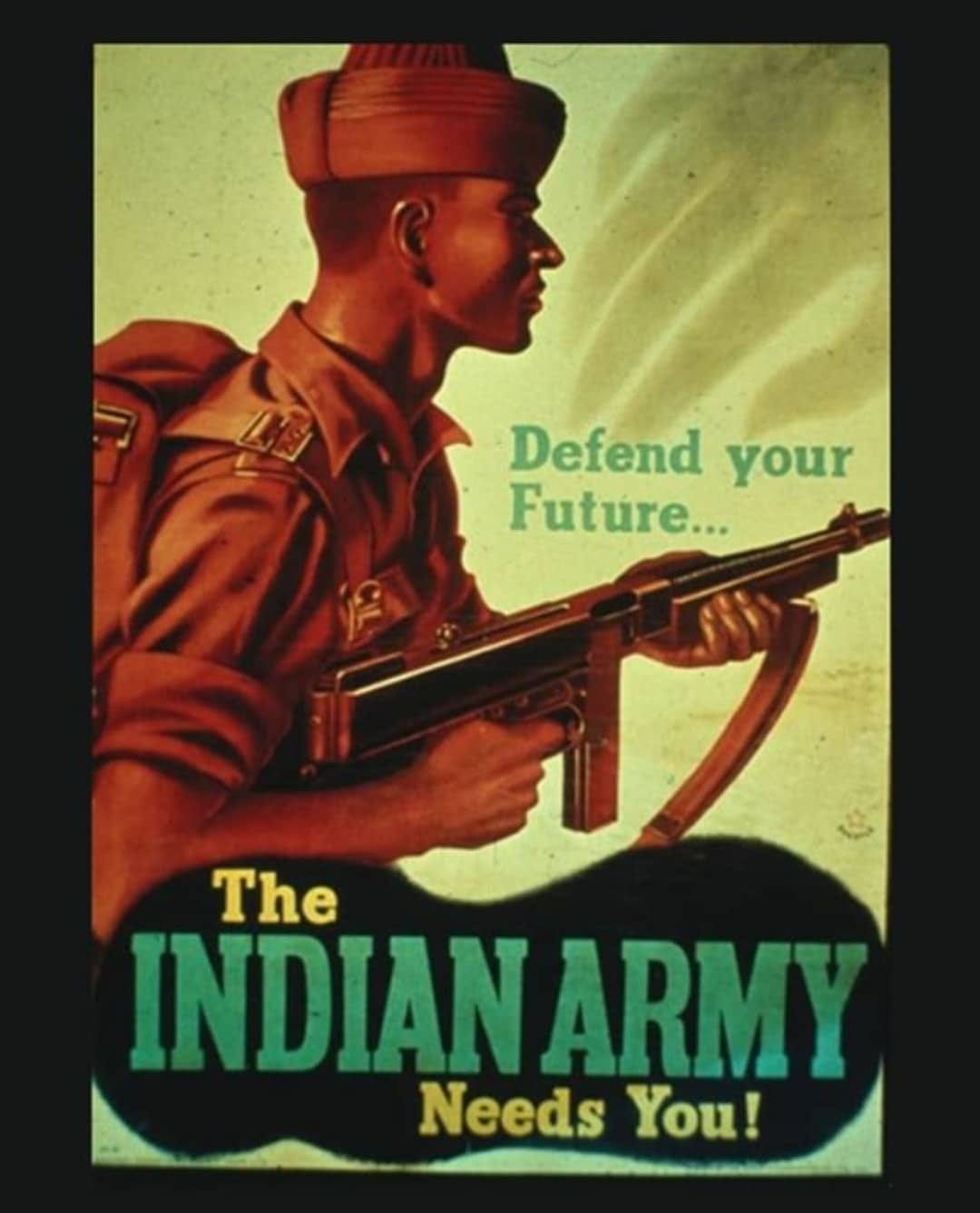

When the Second World War began in the Pacific and Far East in December 1941, it did so with direct attacks on British (and other colonies) and dependencies. The British Empire and Commonwealth became directly engaged in the war with Japan from the very first day – 8 December 1941, the same day as the assault on Pearl Harbor which, because of the International Date Line, fell on 7 December. Hong Kong, Malaya and Burma were first in the firing line. The empire thereafter remained key to British and Allied attempts to defeat the Japanese through to Japan’s eventual surrender on 15 August 1945.

Indeed, it is not possible to consider a British victory in Burma without the huge commitment made by millions of men and women from across the Commonwealth, especially in pre-partition India, together with the support of independent kingdoms like Nepal, and the Princely States, which were not formally part of British India but which were linked to it by treaty.

The war in the Far East constituted the longest period of campaigning by British and imperial forces anywhere in the world during the Second World War. This campaign area became known as South East Asian Command (SEAC), commanded by Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. He had an American deputy, until 1944 Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell. This reflected the importance in Allied strategy of American support to China by means of the incredible airlift over the ’hump’ from the Brahmaputra Valley across the mountains to Yunnan. Indeed 273,000 Americans operated in the theatre to service the Hump airlift and the building of a new Burma Road from Ledo in northern Assam, to replace the one cut-off by the Japanese in 1942. Indeed the USA provided nearly three times as many troops to the fight in the Burma Campaign as the United Kingdom.

In April 1945 the number of Allied service personnel in South East Asia Command (i.e. excluding those in India Command) totalled an incredible 1,304,126. Of this number the British Commonwealth provided 954,985 men and women, of whom 606,149 were soldiers in the fighting brigades, divisions and corps of 14 Army. Of this total of 606,149, 87% were Indian, 3% African and 10% British.

Imperial manpower contributions came from:

1. India, now India

2. India, now Bangladesh

3. India, now Pakistan

4. Burma (now Myanmar)

5. Britain

6. Australia

7. Nigeria

8. Gold Coast (now Ghana)

9. The Gambia

10. Sierra Leone

11. Kenya

12. Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia)

13. Uganda

14. Nyasaland (now Malawi)

15. British Somaliland (now Somalia)

16. Tanganyika Territory (now part of Tanzania)

17. South Africa

As the recent book by Daryl Moran and Andrew Kilsby In The Fight demonstrates, Australians supported the war effort in Burma not in the form of formal battalions, squadrons or units, but primarily by hundreds of individuals and small groups of individuals (and some ships). (As an aside, at the height of its military contribution in 1943, nearly 492,000 Australians were deployed in the South-West Pacific. This alone puts paid to Max Hasting’s unconscionable ‘bludger’ slur. In respect of the Commonwealth contribution to the war effort, the Pacific Theatre also included New Zealanders).

As I showed in my A War of Empires, the Australians led the way in designing effective tactics to defeat the Japanese, lessons that were transmitted profitably to the forces in India facing off against the Japanese in 1943. In 1943, 168 experienced Australian officers were sent to India to assist in training 14 Army.

Other countries, not members of the Commonwealth, also offered support, such as Nepal and the Indian Princely States. In addition to the regular Gurkha regiments of the Indian Army, the Government of Nepal provided 8,889 of its own soldiers to help in the war effort. Indeed, the first two soldiers killed at Kohima in April 1944 were from the Shere Regiment of the Royal Nepalese Army. The Indian Princely States provided 25,112 men, several battalions of infantry serving directly in the war zone. There were also 19,310 men from occupied Burma who remained in British service during the war. Many of these were Karens, Chins and Kachins, from the Burmese hill regions who had provided the bulk of the Burma Army prior to 1941.

The West African colonies, The Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and Nigeria, sent two divisions; from Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika Territory, Nyasaland, British Somaliland and Northern Rhodesia sent a division and two brigades.

African troops were sent to India for operations in Burma in late 1943 after the Axis threat receded following the recommendations of General George Giffard, who had a high regard for their fighting abilities. They proved adept at jungle fighting. In the words of one of their officers, John Hamilton, they were better than Europeans at being ‘resistant to tropical disease and heat, and their sickness rates were to prove among the lowest in Burma.’[i] They were to fight magnificently in the tough conditions of Arakan (now Racine State) between 1943 and 1945 and with the Chindit forces of General Orde Wingate behind Japanese lines in central Burma in 1944. A whole division – the 81 West African Division – operated dependent on air supply in Arakan for 9-months. One battalion was in the jungle for 14-months. Mountbatten was to thank the West Africans for their ‘outstanding services’ and ‘magnificent fighting qualities.’[ii] But the best accolade came from the Japanese, who regarded them to be undoubtedly Britain’s ‘best jungle fighters.’[iii]

Likewise it’s important to remember the significant contribution made to the war effort by indigenous peoples in many places where the war was fought. In eastern India, when it came to choose between the invading Japanese and the existing government, very many supported the latter. This was especially true for the people of the Naga Hills, which lie in northern Assam (now Nagaland) between the Brahmaputra Valley in India, and the Chindwin River valley in Burma. The people of the hills demonstrated their support to the British in a myriad of practical ways, from serving as porters to carrying out casualties, as well as, in some cases, to direct fighting. Many Nagas joined the Assam Rifles, which fought bravely at Kohima in the great battle that stopped the Japanese invasion of India in 1944.

One long forgotten fact about the Commonwealth contribution to the global war against the Axis lay in the financial contributions made to Britain’s war chest. Indian resources were in considerable demand as the war progressed. Britain had agreed to pay India for any costs associated with the provision of men and war materials outside India. As Ashley Jackson explains, in ‘1940-41 Britain paid £40 million towards Indian defence, and India paid £49 million. A year later, Britain was paying £150 million, and India £71 million. In 1942-42, Britain’s bill had soared to £270 million.’[iv] By 1945 Britain owed India £1,260m ‘one-fifth of U.K. Gross National Product.’[v]

One question that is often asked of me is ‘Why did colonial subjects join up in such large numbers to fight what might have been considered someone else’s war?’ I answered this in the recent Channel 4 documentary with journalist Mobeen Azhar (‘The Soldiers Who Saved Britain) with something like this:

“Most Indians who joined the armed forces in such extraordinary numbers, for example, did so because they had assessed the nature of the sacrifice they were willing to make for the sake of defeating the Japanese, regardless of their own lack of political representation. In this sense, their decision was made on the basis of a conception of India much larger than purely politics. Most Indians accepted that the Raj was, rightly or wrongly – or for the time being – the legally constituted Government of India and were prepared to serve in the Indian armed forces in the war against Japan.”

In February 1945 General Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, remarked that ‘every Indian officer worth his salt today is a nationalist.’[vi] An anonymous Indian soldier, quizzed on the subject in Burma in 1945, asserted simply: I have joined the army to serve my country… This is a people’s war.’[vii] Any assessment of the motivation of Indian’s joining the Indian Army after 1939 needs to recognise an essential duality at play; that men and women in colonial India were perfectly capable of having strong nationalistic aspirations while at the same time wishing to join the Indian armed forces because they accepted that the immediate physical threat to their own lives to be an existential one, and threatened their conception of what India should, could and one day would be.

The creation of a war-winning Army in 1944-45 was one of the great national triumphs of wartime India. Too often, remembrance of the ‘Forgotten Army’ – usually referring to General Bill Slim’s 14 Army in Burma – relates to the British rather than the Indian and wider Commonwealth – and even American – contribution.

In fact, victory in Burma in 1945 was largely an Indian one. Vice-Admiral The Earl Mountbatten of Burma made an especial point of emphasising that ‘It was on the Indian troops… that the main brunt of the land fighting fell; and no words of mine could adequately express the unfaltering loyalty and courage of these men.’[viii] Indian soldiers were to win 22 of the 34 Victoria and George Crosses awarded during the Burma Campaign.

By strengthening India’s armed forces, which increased from 194,373 in October 1939 to a total recruited during the war of 2,499,909 million in 1945, recruited from across the entirety of India, it served to strengthen the idea of a capable and effective India, independent of British rule.[ix] The Indian Air Force, which had begun the war with 285 officers and men was now the Royal Indian Air Force, with nine squadrons of aircraft and 29,201 officers and men.[x] As the army increased dramatically in size after 1940, there were many in India, of all political stripes, ‘who saw in the building and expansion of the Army the most practical steps towards the building of a new, free India.’[xi] It is for this – the future, not the past, nor even the present – that they fought.

If you want to come with me to Kohima and a whole host of fascinating places in the hills, let me know. I’m back in India in February 2025 with Sampan followed by two weeks in Myanmar.

[i] John Hamilton ‘African Colonial Forces’ in David Smurthwaite (ed.) The Forgotten War (London: National Army Museum, 1992), p. 68.

[ii] Ibid., p. 73.

[iii] Ibid., p. 74.

[iv] Ashley Jackson The British Empire and the Second World War (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006), p. 356.

[v] Walter Reid Keeping The Jewel in the Crown: The British Betrayal of India (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2016), p. 142.

[vi] David Omissi The Sepoy and the Raj (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1994), p. 242.

[vii] (Anonymous) Indian soldier in Burma, 1945. The National Archives File WO 208/804A.

[viii] Report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff in 1951, Earl Mountbatten, p. 211.

[ix] See F.W. Perry The Commonwealth Armies: Manpower and organisation in two world wars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), pp. 102, 117, and William Arthur The Martial Episteme: Re-Thinking Theories of Martial Race and the Modernisation of the British Indian Army in the Second World War in Rob Johnson The British Indian Army, Virtue and Necessity (Newcastle upon Tyne; Cambridge; Scholars Publishing, 2014).

[x] K.S. Nair The Forgotten Few (Noida, Utter Pradesh; Harper Collins, 2019).

[xi] John Connell Auchinleck: A Critical Biography (London: Cassell and Company, 1959), p. 765.

Thanks Rob, another superb article. I do remember my grandfather saying once that they always felt safer if there was a West African unit on their flank or nearby their Battery.

Excellent article Robert explaining the Commonwealth nations contribution to the 14th Army and arguably lessons which NATO could emulate, I have posted the link on LinkedIn and Bluesky.