Sangshak is a battle that should rest comfortably on the lips of anyone interested in the history of war. For those who don’t know anything about it, I can tell you that it was one of the many scores of ferocious engagements that made up what we generically know as the Battle of Imphal, between March and August 1944. Of course, Imphal wasn’t a single engagement, but a multiplicity of desperate struggles between Mutaguchi Renya’s invading 15th Army and the (mainly) Indian and British defenders of Manipur and the Naga Hills of Assam.

When Wavell, by then Viceroy of India, visited Imphal after the battle in October, to bestow knighthoods on the three victors - Lieutenant Generals Bill Slim (14 Army), Montagu Stopford (33 Corps), Geoffrey Scoones (4 Corps) and Philip Christison (15 Corps) - he admitted to Slim that he found the battle hard to follow, as it seemed to have been fought in ‘penny-packets’. In professing his ignorance of Slim’s great triumph, Wavell nevertheless hit the nail on the head. Sangshak was one of those penny-packet fights which cumulatively determined the outcome of Japan’s audacious invasion of India.

Like many battles in insufficiently examined wars, Sangshak has suffered over the years from a paucity of rigorous examination. Louis Allen’s magisterial The Longest War gave it short treatment in 1984, and very little else. Until now. I’m delighted to say that a Hong Kong-based Australian lawyer with a military background - David Allison - has produced a new account of this crucial battle, and it is absolutely outstanding. It can be purchased here. I recommend it very strongly. Its not long: at 159-pages of text you can make your way through this in a couple of days, but it is diligently researched, well written and judiciously argued. For those who know something of the battle, the big arguments in the past about the state training of the 50 Indian Parachute Brigade, the temporary breakdown of its commander, Hope-Thomson and the supposed loss of the captured Japanese map and orders by HQ 23 Indian Division, are calmly and satisfyingly explained.

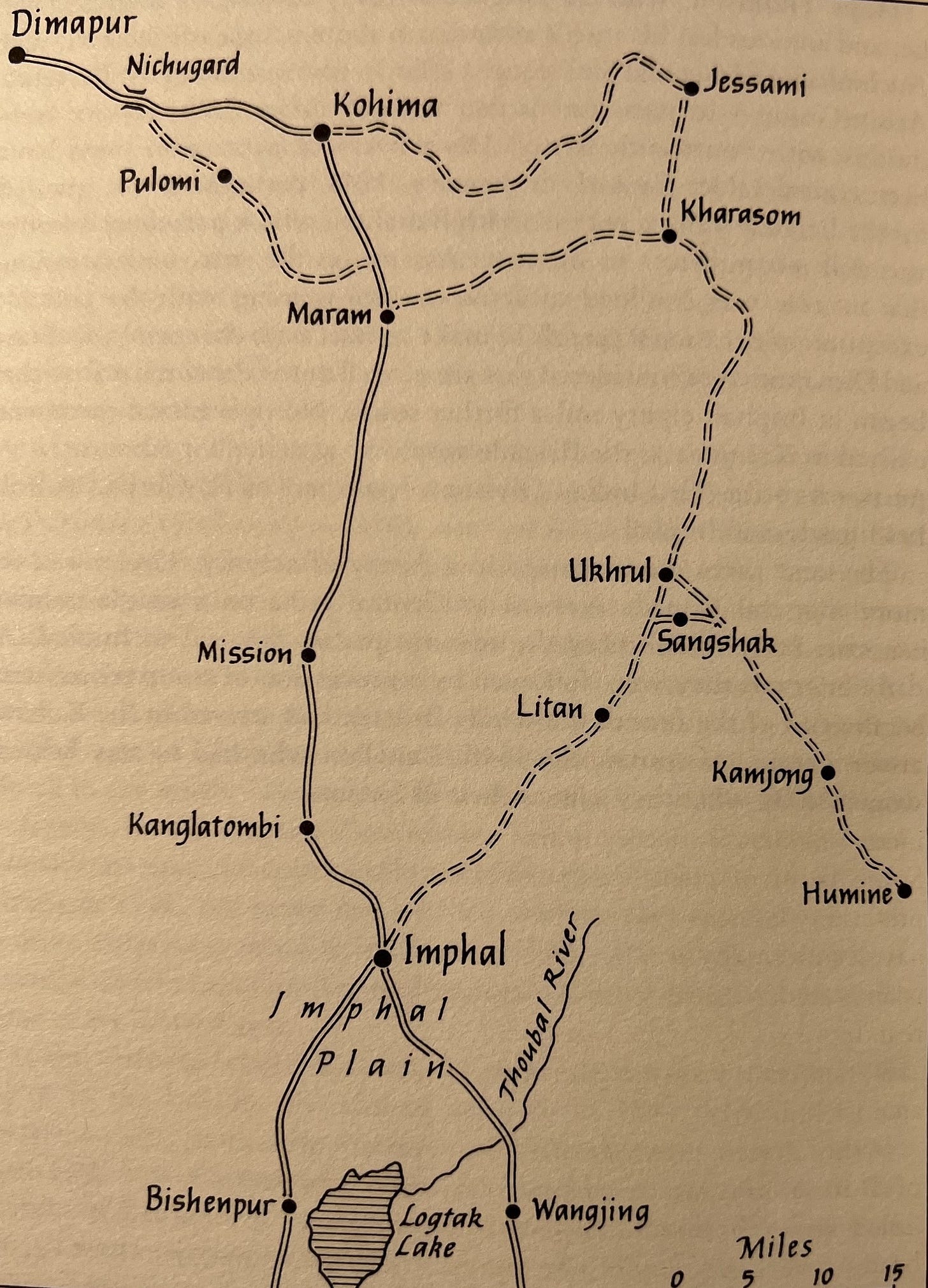

The story can be briefly told. The territory to the north-east of Imphal (centring on the Naga village of Ukhrul) had only the lightest of garrisons and no real defences. Until 16 March it was home to 49 Brigade, which was then despatched to the Tiddim Road to deal with the advance in the south of Lieutenant General Yanagida’s 33 Division. The brigade had considered itself to be in a rear area, and, extraordinarily, no dug-in and wired defensive positions had been prepared. It was one of the most serious British planning failures of the campaign. The entire north-eastern portion of Imphal lay effectively undefended. The gap left by the brigade’s departure had been filled in part by the arrival of the first of the two battalions of the newly raised 50 Indian Parachute Brigade (comprising the Gurkha 152 Battalion and the Indian 153 Battalion), whose young and professional commander, 31-year-old Brigadier M.R.J. (‘Tim’ ) Hope-Thomson, had persuaded New Delhi to allow him to complete the training of his brigade in territory close to the enemy. Th e area north-east of Imphal was regarded as suitable merely for support troops and training. At the start of March, the brigade HQ and one battalion had arrived in Imphal and began the leisurely process of shaking itself out in the safety of the hills north-east of the town. To the brigade was added 4/5 Mahrattas under Lieutenant Colonel Trim, left behind when 49 Brigade was sent down to the Tiddim Road. To Scoones and his HQ, the area to which Hope-Thomson and his men were sent represented the lowest of all combat priorities. Sent into the jungle almost to fend for themselves, it was not expected that they would have to fight, let alone be on the receiving end of an entire Japanese divisional attack. They had little equipment, no barbed wire, and little or no experience or knowledge of the territory. No one considered it worthwhile to keep them briefed on the developing situation. To all intents and purposes, 50 Indian Parachute Brigade was an irrelevant appendage, attached to Major General Ouvry Roberts’ 23 Indian Division for administrative purposes but otherwise left to its own devices.

Before long, information began to reach Imphal that Japanese troops were advancing in force on Ukhrul and Sangshak. Inexplicably, however, this information appeared not to ring any warning bells in HQ IV Corps in Imphal, which was preoccupied with the developing threat in the Tamu area where the main Japanese thrust was confidently predicted. On the night of 16 March, the single battalion of 50 Parachute Brigade took over responsibility for the Ukhrul area from 49 Brigade, which was hastily departing for the Tiddim Road. They had no idea that an entire Japanese division of 20,000 men was crossing the Chindwin in strength opposite Homalin. On 19 March, large columns of Japanese infantry were reported advancing through the hills.

No one had expected them to be where they were. But the first shock came to the Japanese 3/58 battalion (Major Shimanoe), part of Lieutenant General Sato’ s 31 Division – troops whose objective was Kohima, and not Imphal – who were bloodily rebuffed by the determined opposition of the young Gurkha soldiers at an unprepared position forward of Sheldon’s Corner. The 170 Gurkha recruits refused to allow the 900 men of 3/58 to roll over them and inflicted 160 casualties on the advancing Japanese. In the swirling confusion of the next 36 hours, Hope Thomson and his staff kept their heads, attempting to concentrate what remained of the dispersed companies of 152 Battalion and 4/5 Mahrattas back to a common position at the village of Sangshak, which dominated the tracks southwest to Imphal.

It was at this now-deserted Naga village that Hope-Thomson, on 21 March, decided to group his brigade for its last stand, his staff desperately attempting to alert HQ 4 Corps in Imphal to the enormity of what was happening to the north-east. The Japanese columns infiltrated quickly around and through the British positions, heading in the direction of Litan. The Japanese now began days of repeated assaults on the position in a battle of intense bravery and sacrifice for both sides. Hope Thomson’ s men could only dig shallow trenches, which provided no protection from Japanese artillery.

Like all Naga villages, Sangshak was perched on the hill and had no water: anything the men required had to be brought up from the valley floor, through the rapidly tightening Japanese encirclement.

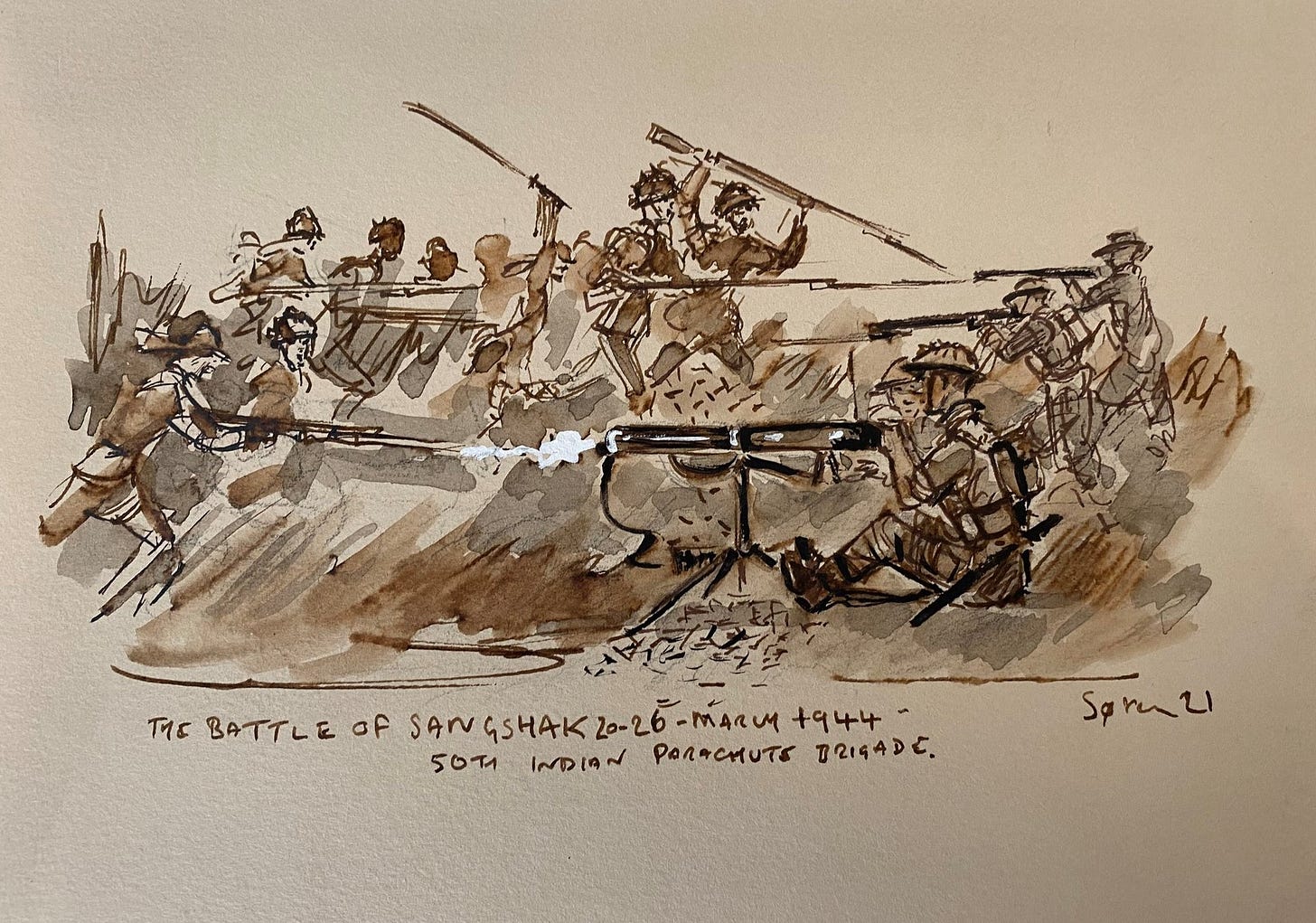

Major General Miyazaki decided that he needed to eliminate the defenders of Sangshak, probably because they posed a threat to his long lines of supply and communication to Kohima, despite the fact that he knew Sangshak to lie not in his, but in 15 Division’ s area of responsibility. Accordingly, he despatched both the Second Battalion (2/58, commanded by Major Nogoya) as well as 3/58 to Sangshak where they arrived late on 22 March. Hoping to overwhelm the defenders, the Japanese attacked immediately, throwing infantry forward into the assault without undertaking a detailed reconnaissance of the enemy position, or waiting for the arrival of supporting artillery. It was a serious error. The 400 waiting Gurkhas of 153 Battalion could not believe the sight before them as, facing north-west across the valley to West Hill in the failing light of early evening, a swarming mass of enemy rushed to overwhelm what they had imagined to be weak and puny defences. Wave after wave of enemy were cut down as they ran down the slopes of the hill, into the precision fire of 153’s Lee-Enfields and the chattering Vickers firing above and behind them. In addition to the four mountain guns, Hope-Thomson’s brigade was also blessed with 3-inch mortars.

In fact, 8 Company of 2/58 lost 90 men from a total of 120, including Captain Ban, its company commander, in the space of 15 minutes. They learned their lesson, however, and the defenders of Sangshak never again faced such ripe targets. Instead, as the days drew out, they were subjected to increasingly frantic Japanese efforts to break into Hope-Thomson’s position. Although the weight of Japanese attacks tended to be on the north and west of the perimeter facing 152 and 153 Battalions, as the days went by increasingly strong probes were made against the Mahrattas on the eastern edge.

Hope-Thomson’s men found themselves alone and faced by heavy odds. Fortunately, however, and at long last, Imphal had now awoken to the enormity of the threat on its north-eastern perimeter, Roberts signalling to Hope-Thomson on 24 March, five days after the fi rst appearance of the Japanese, ‘Well done indeed. You are meeting the main Jap northern thrust. Of greatest importance you hold your position. Will give you maximum air support.’

Gallant attempts to drop precious water to the beleaguered troops, as well as ammunition for the mortars and mountains guns, largely failed, as much as three-quarters of these valuable cargoes frustratingly floating down to the Japanese. Unfortunately, with no barbed wire, no water and rapidly diminishing reserves of ammunition, the long-term prognosis for the hugely outnumbered 50 Indian Parachute Brigade was never in doubt if Miyazaki decided to delay his advance to Kohima in order to crush the defenders. The final day came on Saturday 26 March. With the sun beating down mercilessly on the parched defenders, the Japanese closed in from all sides, with bullet, bayonet and grenade, desperate to break the hold that the defenders had placed on 31 Division’s advance. In a day of fierce attack and counterattack across the Sangshak Plateau, the brigade lost more men than in the fighting so far. That night HQ 4 Corps recognized the inevitable and ordered the survivors to break out and make their way as best they could to Imphal. The immovable wounded, some 150 men, had to be left behind, and the remaining 300 wounded had to walk out with the rest.

While 50 Parachute Brigade was virtually destroyed in the four days of the Sangshak battle (152 Gurkha Battalion lost 350 men – 80 per cent of its strength – and 153 Indian Battalion lost 35 per cent), considerable benefit fell to 4 Corps by their sacrifice. The battle cost Miyazaki probably 1,000 casualties and his advance was held up for a week, causing serious delay to Sato’ s plans for Kohima. From both 2/58 and 3/58, Miyazaki had lost six of his eight company commanders, as well as most of the platoon commanders. Miyazaki’s speculative attack on Sangshak drew him into an unnecessary battle of attrition that delayed the journey of his column to Kohima and proved in time to be a serious setback to Mutaguchi’s hopes of capturing all of his objectives within three weeks. It was a common problem among Japanese commanders, who repeatedly sought battle for the glory of it. It would have been far better to have left Hope-Thomson’s brigade where it was and hurried on to their objective. The parachute brigade could then have been dealt with later. Too often, however, Japanese commanders failed to understand the nature of military strategy, and to differentiate between the strategic task and the tactics required for its achievement. Something – bushido perhaps – acted as a magnet to the egos of some Japanese commanders, dragging them into unnecessary fights to sate their need for blood and glory.

David Allison’s excellent new book fills a yawning gap in our understanding of what happened in one of the many, crucial through relatively small battles fought around the Imphal Plain and which played such a dramatic though until now largely unappreciated aspect of the campaign which turned back Japan’s invasion of India in 1944. It is unreservedly recommended.