Last Saturday, in front of a packed audience (over 1,000 people came through the National Army Museum last weekend for our ‘Kohima, 80th Anniversary’ commemorations) I reprised the 2011 debate in which I argued that the twin battles of Kohima and Imphal in 1944 were Britain’s Greatest Battle. It was a debate: you don’t have to agree with me, but what follows is the substance of my argument.

Let’s first tell something of the story of this battle.

It is clear to me that the great twin battle of Imphal & Kohima, which raged from March through to late July 1944, was one of four great turning-point battles in the Second World War, when the tide of war changed irreversibly and dramatically against those who initially held the upper hand.

The first great turning point was arguably at Midway in June 1942 when the US Navy successfully challenged Japanese dominance in the Pacific. The second was at Stalingrad between August 1942 and January 1943 when the seemingly unstoppable German juggernaut in the Soviet Union was finally halted in the winter bloodbath of that city, where only 94,000 of the original 300,000 German, Rumanian and Hungarian troops survived. The third was at El Alamein in October 1942 when the British Commonwealth triumphed against Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa and began the process that led to the German surrender in Tunisia in May 1943. The fourth was this battle, that at Kohima and Imphal between March and July 1944 when the Japanese “March on Delhi” was brought to nothing at a huge cost in human life, and the start of their retreat from Asia began. Adjectives such as “climactic” and “titanic”, struggle to give proper impact to the reality and extent of the terrible war that raged across the jungle-clad hills during these fearsome months.

That the Japanese were contemplating an offensive against India in early 1944 was a surprise to Allied planners, who had given no thought to its possibility. By this time Japan had reached the apogee of its power, having extended the violent reach of its Empire across much of Asia since it launched its first surprise attacks in late 1941. Its initial surge in 1942 into what was briefly to be Japan’s ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’ was as dramatic as it was rapid and two years further on several millions of peoples across Asia laboured under its heavy yoke. But by early 1944 the tide had turned decisively in the Pacific, the American island-hopping advance reaching steadily but surely towards Japan itself, its humiliated enemies fighting back with desperation, and with every ounce of energy they could muster. They were beginning to prevail in the fight although the struggle on the landmass of Asia was a strategic sideshow in the context of a global conflict: at this time the British and American High Commands were totally occupied with Europe and the Pacific. The British and Americans were preparing for D Day. The Soviets were advancing in Ukraine. There was a stalemate in Italy at Monte Cassino. The Americans were preparing to land in the Philippines. Germany and Japan were both in retreat, but not defeated. In this global context India and Burma appeared strategically peripheral, even inconsequential. Yet in this month, at a time when on every other front the Japanese were on the strategic defensive, Japan launched a vast, audacious offensive deep into India in an attack designed to destroy for ever Britain’s ability to challenge Japan’s hegemony in Burma.

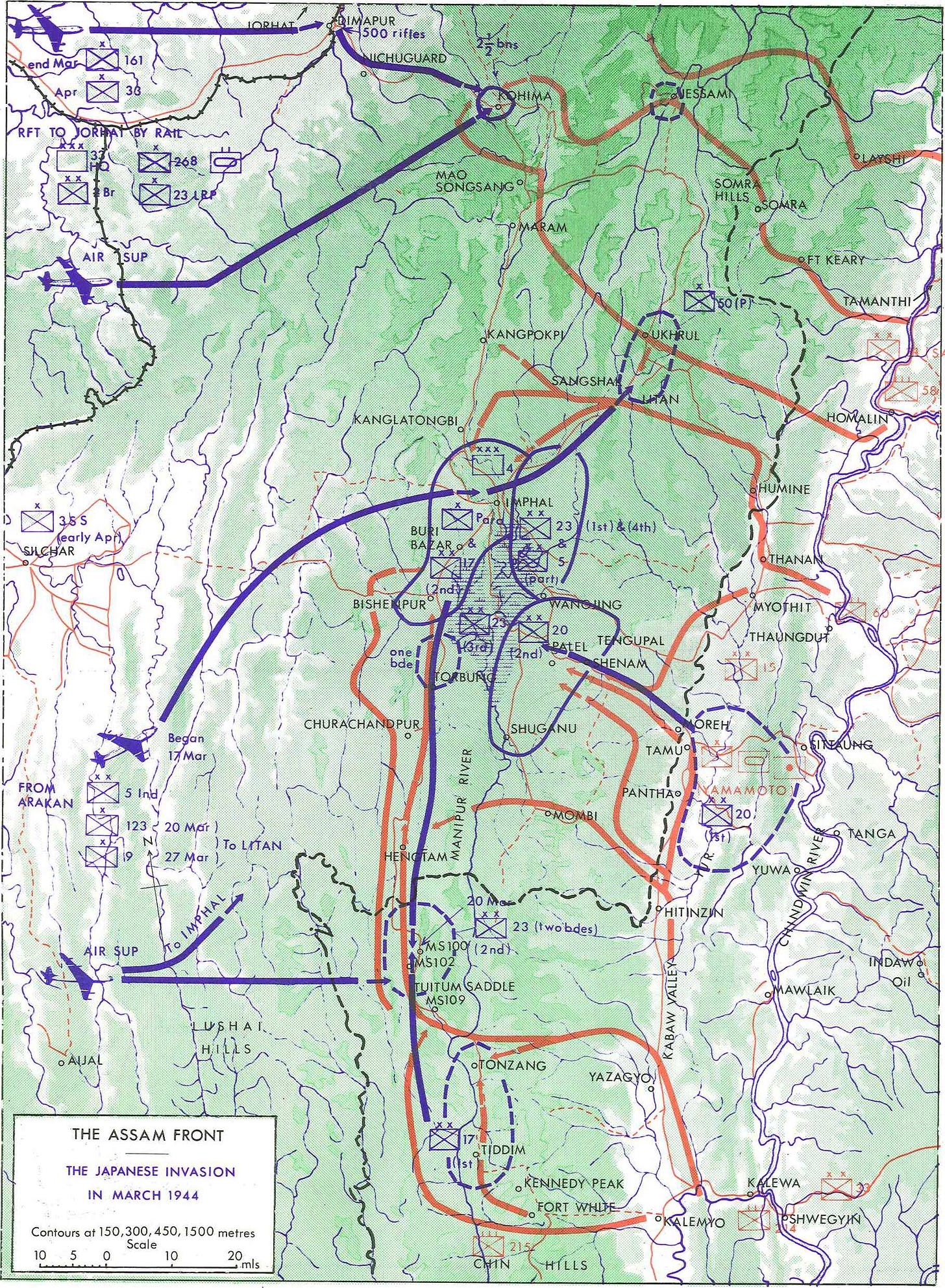

The Japanese commander was General Mutaguchi Renya, a gutsy go-getter who had played a significant role in the collapse of Singapore in February 1942. His evaluation of the British position in northeast India revealed that the three key strategic targets in Assam and Manipur were Imphal; the mountain town of Kohima, and the huge supply base further back on the edge of the Brahmaputra Valley at Dimapur. If Kohima were captured, Imphal would be cut off from the rest of India by land. From the outset Mutaguchi believed that with a good wind Dimapur, in addition to Kohima, could and should be secured. He reasoned that capturing this massive depot would be a devastating, possibly terminal blow to the British ability to defend Imphal, supply the Americans in Northern Burma under Vinegar Joe Stilwell, support the Hump airlift into China and mount an offensive into Burma. It would also enable him to feed his own, conquering army, which would advance across the mountains from the Chindwin on the tightest imaginable supply chain. With Dimapur captured, the Japanese-led Indian National Army under the Bengali nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose could pour into Bengal, initiating the long-awaited anti-British uprising.

The essence of the battle for India in 1944 can be quickly told. Mutaguchi's 15th Army advanced in four separate columns into Manipur. The Japanese made determined, even desperate, efforts to seize their objectives: in the north Kohima, with a scratch British and Indian garrison of 1,200 trained fighting soldiers – about two thirds of them Indian – was attacked by an entire division of about 15,000 men in early April. Surrounded and slowly forced back onto a single hill they were supplied by air until relief came on 20 April, although the battle to dislodge the Japanese from Kohima continued bloodily, in appalling weather and battlefield conditions – the annual monsoon was in full spate – through to early June. Further south the Japanese plan entailed attacking Imphal from north, east and south. The plan of the commander of the 14th Army, Lieutenant General Bill Slim, was to withdraw his forces into the hills and there to allow the Japanese to expend themselves fruitlessly against well-supplied and aggressive British bastions, equipped with tanks, artillery and supported by air. The battle for Imphal in Manipur and for Kohima to the north-west in the neighbouring Naga Hills settled down to a bloody hand-to-hand struggle as the Japanese tried to gain the foothold necessary for their survival. They travelled lightly, and reserves soon exhausted themselves and further supplies were almost non-existent. Just as the air situation was becoming critical for Slim through poor weather and shortages of aircraft the relieving division from Kohima – the British 2nd Infantry Division that had last seen action at Dunkirk – began fighting its way towards Imphal, and the four beleaguered divisions began to push out from the Imphal pocket. By 22 June the 2nd Division and the 5th Indian Division met north of Imphal and the road to the plain was open. Four weeks later the Japanese withdrawal to Burma began.

Of all the invading armies of history, it is hard to think of one that was repulsed more decisively, or more ignominiously, than the Japanese 15th Army launched against India in March 1944. Its defeat was not the fault of the Japanese soldiers, who fought courageously, tenaciously and fiercely, but of their commanders, who sacrificed the lives of their troops on the altar of their own hubris. The battle had provided the largest, most prolonged and most intense engagement with a Japanese army yet seen in the war. ‘It is the most important defeat the Japs have ever suffered in their military career’ wrote Mountbatten exultantly to his wife on 22nd June 1944, ‘because the numbers involved are so much greater than any Pacific Island operation.’ The extent of the disaster that befell the 15th Army is captured by a comment by Kase Toshikazu, a member of the wartime Japanese Foreign Office, who lamented: ‘Most of this force perished in battle or later of starvation. The disaster at Imphal was perhaps the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war.’ The latter might better have included the caveat ‘Japanese’ to avoid charges of exaggeration, but his comment captures something of the enormity of the human disaster that overwhelmed the 15th Army. It might more fairly be described as the greatest Japanese military disaster of all time. The Indian, Gurkha, African and British troops of this remarkably homogeneous organisation had also decisively removed any remaining notions of Japanese superiority on the battlefield.

The importance of this victory was overshadowed at the time, and downplayed for decades afterwards, by the massive victories in 1945 which brought World War II to an end in Europe and the Pacific. But this lack of publicity and of awareness does not remove the fact that, objectively speaking, the battles in India in 1944, epitomized in the fulcrum battle at Kohima, were an epic comparable with Thermopylae, Gallipoli, Stalingrad, and other better known confrontational battles where the arrogant invader became, in time, the ignominious loser.

Yet the victory was hailed at the time more with relief than with triumph, because it was not a defeat. It was also seen as giving the Allies a new headache: the practicality of an offensive directly into Burma, which the Chiefs of Staff in London had long resisted, preferring the option of an amphibious assault against Northern Malaya. But the dramatic success of Slim’s 14th Army in Assam and Manipur in 1944 opened up for the first time the prospect of the reconquest of Burma by land. And this, in 1945, is precisely what, against every expectation, it achieved. We have no time to discuss that great campaign here today, but the 1944 victory was not only was a turning point in the war against the Japanese, but it precipitated the reconquest of Burma in 1945.

The Japanese invasion of India in 1944 was also the last time Britain was forced to defend its empire – Suez in 1956 and the Falklands in 1982 were hangovers. New and old empires collided in India in 1944. In the searchlight of history, neither had any right to be there. However, the British victory was profound. It did not, as some had feared, strengthen British determination to bolster her empire, at least by military means, but rather confirmed its perception that the time was approaching when it should give it up. In the short term, it made a dramatic impact on the morale of the Allies fighting back the tide of fascist militarism that had appeared at one stage unstoppable. Although it made little impact on the final outcome of the war against Germany and Japan it had undeniably strategic consequences. Politically, it removed any claim that India was ripe for civil war. The possibilities available to the militant nationalism of Subhas Chandra Bose were never a match for the peaceful and powerful drive for political self-determination led by Gandhi and Nehru. It also demonstrated forcefully to the Japanese the harsh reality of defeat, for there was no doubt that Japan had been comprehensively beaten. Their earlier defeats had ousted them from, or destroyed them in, territories which they had captured. They suffered this defeat when attempting to advance. In the physical defeat of the Japanese in India in 1944 the hard lesson was taught to a nation previously drunk on expansionist ambition that aggression of this type had no long term reward and belonged to a previous, less intelligent age.

Now, to really judge whether the suggestion that this battle was a ‘great battle’ we need to start by defining our terms. What is meant by a ‘great’ battle? I approached the question by determining that that to be defined as such a battle needed to meet the following nine criteria:

First, the intensity of the combat had to be severe. We are not talking here about a skirmish, or a quick assault before breakfast and a cup of tea to follow, but a major conflict of arms.

Second, it has also to be an occasion of crisis, in which the fate of the nation or issues of real strategic significance are at stake. It couldn’t really apply to operations that were long in the planning, like Gallipoli, or even D Day.

Third, it has to represent a turning point in a war, or in a campaign, for better or for worse.

Fourth, clear victory is achieved for one party, and clear defeat for the other.

Fifth, it is one which has evenly matched opponents. I have thought long and hard about this one, and conclude that for a battle to be judged ‘great’ it needs to to be much more than a one-sided match, even if its size and scale means that it contained considerable bloodshed and high drama.

Sixth, the battle needs to be one which was of historical significance above and beyond the clash of arms and the human drama of the occasion.

Seventh, it needs to be one which took place in a dramatic setting, physically and perhaps geographically

Eighth, it needs to be one in which the calibre of the soldiers involved, and of the leadership demonstrated, contributed measurably to the outcome.

It needed to involve new methods of warfighting, with perhaps innovative methods of defeating the enemy. No prizes can be awarded for unintelligent slogging mathes that produce nothing but high butcher's bills.

It seems clear to me that the scale of the battle, and the number of casualties incurred, cannot be not proper measures of greatness.

It also seems clear to me that a number of other British battles – El Alamein, Cassino, Arnhem and Waterloo, for instance – all had the qualities I have just listed. So too, does Kohima. So what, in my view makes Kohima unique? I would like to propose a list of eleven reasons that in my view moves this battle merely from being ‘great’, to the ‘greatest’ we as a country have ever fought.

First, the boldness, audacity and shock of the Japanese offensive into India in March 1944 challenged the defence of India, and thus not just Britain’s ability to wage war against Japan, but to govern India herself.

Second, the dramatic recovery plan put in place almost overnight, including the mass airlift of two divisions directly onto the battlefield by men who had never flown in aircraft before, and a third – the famous British 2nd Division – dispatched 2,000 miles across the length of India from its encampment near Bombay

Third, the challenges posed by the extreme physical conditions in the vast spread of mountains that separate India from Burma

Fourth, the do-or-die nature of the fighting. The Japanese had to destroy the British in the mountain border with Burma; and the British had to stop them. Great things were at stake, including perhaps even the security of India in a war with the toughest enemy any British army has ever had to fight.

Fifth, the clash of cultures between the two countries represented a profound separation of world views, of behaviour and attitude to life that made this battle appear to be one between two entirely different species.

Sixth, the fact that this battle, combined with its precursor in Arakan the previous month, represented the first ever defeat by the British of the Japanese in battle since the Japanese had swept into south-east Asia in December 1941. The victory enjoyed by the 14th Army in India was thus of profound significance because it demonstrated categorically to the Japanese that they were not invincible. This was to be very important in preparing the entire Japanese nation to accept defeat and to recognise that a negotiated peace settlement on their terms was out of the question. The arrogance of Japanese militarism was that it believed unquestioningly the samurai myth that they were unbeatable in battle. When, a few years ago I interviewed a Japanese veteran of Kohima I asked him to explain the reasons for the Japanese defeat. He almost lost his temper. 'We weren't defeated' he retorted angrily. 'We simply ran out of food and ammunition, and were forced to withdraw.' Allowing the Japanese military and the Japanese people to know that they had been defeated was the only way in 1944 and 1945 of ensuring that militarism, so closely ingrained in the Japanese culture of the time, did not re-emerge after the war as it did in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s.

Seventh, it also demonstrated unequivocally to British and Commonwealth troops that they were able to confront the Japanese in battle, and win. By 1944 British and Indian forces in eastern India had been strenuously retrained and prepared to withstand the extraordinary physical and mental demands required of men fighting the Japanese, following the disasters of 1942 and 1943. Lieutenant General Bill Slim – who had taken command of the newly formed 14th Army in August 1943 – was convinced that he could transform the fortunes of his troops, despite the many gainsayers who loudly claimed the Japanese to be unbeatable. The taste of victory in both Assam and Arakan injected into the 14th Army a newfound confidence based on the irrefutable evidence that the Japanese could be beaten. ‘Our troops had proved themselves in battle the superiors of the Japanese’ commented Slim with satisfaction; ‘they had seen them run’. This victory allowed Slim to conduct an aggressive pursuit in Burma in late 1944 and by mid-1945 to defeat the Japanese for a second time, bringing about the profound collapse of Japanese arms in Burma that year, setting the seal on the process of victory that had begun the year before at Imphal and Kohima.

Eighth, this was a battle in which the indigenous population were not passive observers of the fighting, but one who contributed significantly to the fighting, and without whom British success would have been much less certain.

Ninth, this was the last real battle of the British Empire and the first battle of the new India. Approximately eighty seven per cent of the 14th Army in 1944 and 1945 was Indian, all volunteers who made a conscious decision to fight against Japanese fascism. They weren't fighting for the British or the Raj, but for a newly emerging and independent India and against the totalitarianism of Japan. I have been told this repeatedly by Indian veterans. In fighting with Britain against the Japanese, they were affirming their own nationhood. The success of the Indian Army in 1944, and then in 1945, can be seen as the birth pangs therefore of a new India, democratic and soon-to-be free.

Tenth, this was primarily a foot-soldier’s battle, where the courage and dogged perseverance of the fighting men on both sides contributed to the awful and relenting drama of the battle. The fighting skill and tenacity of the Commonwealth soldiers in Slim's 14th Army proved to be a significant reason for their success. Although the troops – Indian, British and West African alike – might still claim that they were the ‘Forgotten Army’, by 1944 there was no doubt about the strength and depth of the hard won esprit d’corps that now lay at the heart of the army; a sense of moral power that was sealed in the heat of battle and the realisation of victory. They had taken on the most fearsome enemy the British Army had ever encountered in its history, and had conquered. It was also a battle in which new and relatively unknown military leaders emerged, triumphant as much in battle as in strategy.

Eleventh, and finally, the battle saw the deployment by Slim of an approach to warfighting we have since come to describe as 'manoeuvrist'. This means that he deployed his forces in such a way that he sought to defeat Mutaguchi as much by subtlety and guile as by firepower.

The fact that Kohima continues to play a subconsciously integral part of British history can be seen in the fact that no remembrance ceremony today is complete without a recitation of the following words:

When You Go Home,

Tell Them Of Us And Say

For Your Tomorrow,

We Gave Our Today

These words adorn the memorial to the 2nd Division in Kohima, the place of extraordinary sacrifice in 1944, and one of the most humbling places on earth.

Lord Louis Mountbatten called Kohima “one of the greatest battles in history, of naked unparalleled heroism, the British/Indian Thermopylae”.

But does all this mean that the twin battles of Kohima and Imphal were indeed Britain’s greatest battle?

The answer in my view is unequivocally ‘YES!’

Just as good a read as it was a listen back when you presented the case at the NAM

Only two weeks ago I was in a meeting discussing a commemoration event to be held in June. Great emphasis was put on talking of D Day and Normandy. I pointed out that the RAF Regiment we were concerned with had deployed similar numbers to Imphal as in Normandy (and from December 1943 to late 1944, and under far less salubrious conditions!). The comment that came back was that "we can't recognise every 'small' battle that we were involved in during 1944." There is still a lot of work to be done in explaining the significance of the Kohima-Imphal battles, and indeed the consequences of failure by 14th Army for the position in India. I was surprised this view still exists, but then again, I suppose I wasn't. This has faced Burma veterans and those studying the campaign since 1944.