How many British generals have been able to write as well as they could fight? Strangely perhaps, quite a few. Field Marshal Sir Michael Carver (Dilemmas of the Desert War, The Seven Ages of the British Army), General Sir David Fraser (And We Shall Shock Them), General Sir John Hackett (The Third World War) and Major General John Strawson (Beggars in Red) are four outstanding soldier-writers that spring immediately to mind. Even Monty wrote his memoirs. And in our own day I’ve read plenty of competent books from a slew of men who’ve reached the top of the profession of arms. The work of some, like that of General Sir Richard Sherriff (2017: War with Russia), Major General Mungo Melvin (Manstein) and Brigadier Allan Mallinson (Too Important for the Generals et al), could be described as outstanding. Julian Thompson and Richard Dannatt also fit this bill. But by far and away the best of Britain’s soldier-writers in the last century was also probably the greatest soldier – and field commander – of them all: Bill Slim. He was, more properly, Field Marshal William J. Slim KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ, the onetime General Officer Commanding the famous 14th Army – the so-called Forgotten Army – of Burma fame. He was, in this author’s view, the greatest British general of the last war (to avoid further debate, let’s just agree that Monty failed as a coalition commander, whereas Slim excelled). Slim’s ability as a general is perfectly summed up by the historian Frank McLynn:

Slim's encirclement of the Japanese on the Irrawaddy deserves to rank with the great military achievements of all time – Alexander at Gaugamela in 331 BC, Hannibal at Cannae (216 BC), Julius Caesar at Alesia (58 BC), the Mongol general Subudei at Mohi (1241) or Napoleon at Austerlitz (1805). The often made – but actually ludicrous – comparison between Montgomery and Slim is relevant here... there is no Montgomery equivalent of the Irrawaddy campaign… Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius.'[1]

Some hint of Bill Slim’s fluency with the written word to complement his ability as a soldier came with the publication of Defeat into Victory in 1956, his superb retelling of the Burma story. Apart from its remarkable tale – the humiliation of British Arms in 1942 eventually overturned by a triumphant (and largely Indian) army in 1945 (87% of Slim’s army was Indian) – the quality of the writing was astonishing. Its author, a man who would be appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1949 (following Monty), the first Sepoy General ever to do so, and by Attlee no less, could clearly wield a pen every bit as he could destroy Japanese armies in battle (a feat he achieved twice, first in 1944 and again in 1945). When the book was first published it was an instant publishing sensation with the first edition of 20,000 selling out immediately. The Field recorded: ‘Of all the world's greatest records of war and military adventure, this story must surely take its place among the greatest. It is told with a wealth of human understanding, a gift of vivid description, and a revelation of the indomitable spirit of the fighting man that can seldom have been equalled – let alone surpassed – in military history.’ The London Evening Standard was as effusive in its praise: ‘He has written the best general's book of World War II. Nobody who reads his account of the war, meticulously honest yet deeply moving, will doubt that here is a soldier of stature and a man among men.’ The author John Masters, who served in the 14th Army, wrote in the New York Times on 19 November 1961 that it was ‘a dramatic story with one principal character and several hundred subordinate characters,’ arguing that Slim was ‘an expert soldier and an expert writer’. The book remains a best seller today.

The following year Slim also published an anthology of speeches and lectures, loosely based on the theme of leadership, called Courage and Other Broadcasts. Then in 1959 he published his second book, Unofficial History, which bears out in full Masters’ description of Slim as a superb writer. It was a deeply personal, honest though light hearted account of events during his service. It received widespread acclaim. The author John Connell described it as ‘for the most part uproarious fun. If Bill Slim hadn't been a first-rate soldier, what a short story writer he might have made.’ For its part, The National Review wrote: 'One of the most significant aspects of Field Marshal Slim's book is the affectionate respect he shows when he writes about British and Indian soldiers. He finds plenty to amuse him too. I doubt whether a kindlier or truer description of the contemporary soldier has been given anywhere than in Unofficial History... It is one of the most delightful and amusing books about modern campaigning I have ever read.’

What only a handful of people knew at the time was that, in terms of writing, Bill Slim had form. The publication in 1959 of Unofficial History was the first indication that there was an unknown literary side to Slim. The secret was only publicly revealed on the publication of his biography in 1976 by Ronald Lewin – Slim, The Standard Bearer – which incidentally won the W.H. Smith Literary Award that same year. Lewin explained that Slim had written material for publication long before the war. In fact, between 1931 and 1940 he had written a total of 44 articles, extending in length between two and eight thousand words – a total of 122,000 words in all – for a range of newspapers and magazines, including Blackwood’s Magazine, the Daily Mail, the Evening Express and the Illustrated Weekly of India. According to Lewin, he did this to supplement his earnings as an officer of the Indian Army. He didn’t do it because he had pretensions to the artistic life, but because he needed the money. As with all other officers at the time who did not have the benefit of what was described euphemistically as ‘private means’ he struggled to live off his army salary, especially to pay school fees for his children, John (born 1927) and Una (born 1930). Accordingly, he turned his hand to writing articles under a pseudonym, mainly of Anthony Mills (Mills being Slim spelt backwards) and one time as ‘Judy O’Grady’. With the war over, and senior military rank attained, he never again penned stories of this kind for publication. With it died any common remembrance of his pre-war literary activities. Copies of the articles have languished ever since amidst his papers in the Churchill Archives Centre at the University of Cambridge.

During the time he was writing these the pseudonym protected him from the gaze of those in the military who might believe that serious soldiers didn’t write fiction, and certainly not for public consumption via the newspapers. He certainly went to some lengths to ensure that his military friends and colleagues did not know of this unusual extra-curricular activity. In a letter to Mr S. Jepson, editor of the Illustrated Times of India on 26 July 1939 (he was then Commanding Officer of 2/7th Gurkha Rifles in Shillong, Assam) he warned that he needed to use an additional pseudonym to the one he normally used, because that – Anthony Mills – would then be immediately ‘known to several people and I do not wish them to identify me also as the writer of certain articles in Blackwood’s and Home newspapers. I am supposed to be a serious soldier and I'm afraid Anthony Mills isn’t.’

Now, for the first time in many cases since they were first penned, all 44 articles have been republished in three short volumes by Sharpe Books, giving the modern reader a view of the pre-war secret Slim, hiding his literary light under a bushel of military convention. He would never have pretended that his writings represented any higher form of literary art. He was, first and foremost, a soldier. But, as readers will attest, he was very good at it. They show his supreme ability with words. As Defeat into Victory was also to demonstrate, he was a master of the telling phrase every bit as much as he was a master of the battlefield. He made words work. They were used simply, sparingly, directly. Nothing was wasted; all achieved their purpose.

The articles also show Slim’s propensity for storytelling. Each story has a purpose. Some were simply to provide a picture of some of the characters in his Gurkha battalion, some to tell the story of a battle or of an incident while on military operations. Some are funny, some not. Some are of an entirely different kind, and have no military context whatsoever. These are often short adventure stories, while some can best be described as morality tales. A couple of them warned his readers not to jump to conclusions about a person’s character. Some showed a romantic tendency to his nature.

The stories have been each allocated to one of three volumes. The first contains seventeen stories about the Indian Army, of which the Gurkha regiments formed an important part. The second are eleven stories about India, with no or only a passing military reference. The third, much shorter volume, contains seventeen stories with no Indian or military element. With the onset of war in 1939, Slim’s interest in pursuing his literary ventures rapidly waned and was never renewed. Thanks to Sharpe Books, available exclusively through Amazon, a new readership can enjoy Slim’s deft demonstration that his pen was at least equal to his sword.

Links

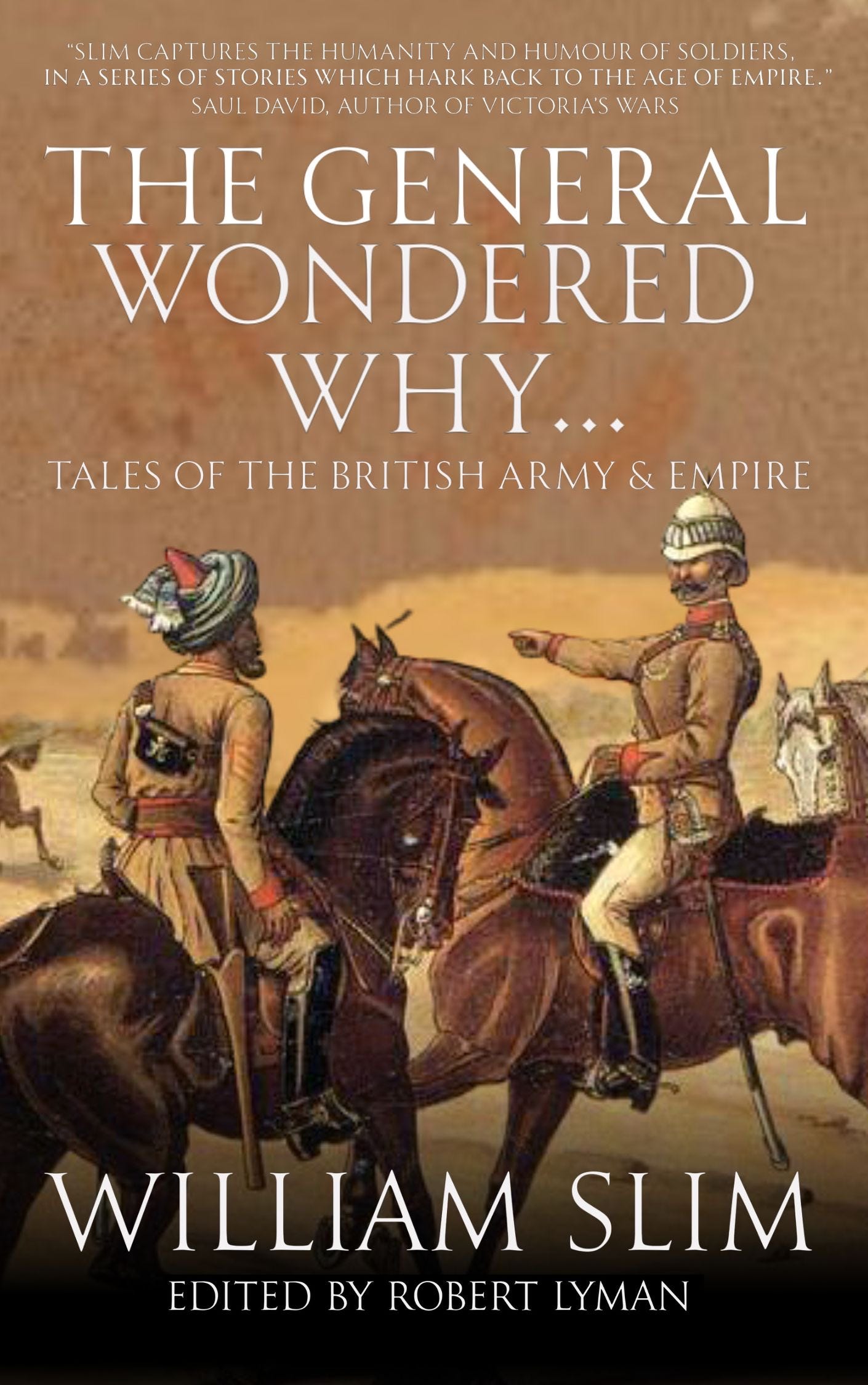

1. The General Wondered Why https://amzn.eu/d/45gHfOH

2. The English Colonel https://amzn.eu/d/ahZJY67

3. A Close Shave https://amzn.eu/d/9exEf3A

[1] Frank McLynn The Burma Campaign (London; Bodley Head, 2010), p. 432.

Montgomery's character and writing style in his memoirs displays how ghostwriters weren't around in the 1950s. But Montgomery is the odd one out in the writing style stakes, something that I noticed when reading Francis Tuker's The Pattern of War and While Memory Serves. However, I have not read Tuker's poetry entitled The Desert Rats.

Since I borrowed your copy of “Courage - and Other Broadcasts” I have gone on to buy each of my 3 sons a copy plus another 2 copies

I think that it is a truly great little book which, if the sentiments are followed by society at large, could solve many of the problems we fact today in said society

I refer to it often