America and the rise of Nazism in Europe

Why the rise of fascism in Germany 1933-36 was ignored until it was too late

January 30, 1933. It is a typically cold mid-winter day across northern Europe. In London, the world’s largest city, fresh winds blow. Across southern England intermittent rain, sleet and snow keep people indoors. In Germany that night a political winter sets in that is to last for more than twelve years and encase the entire world in its frozen embrace. In The Times the following day Canadian-born journalist Matthew Halton described the events in Berlin the previous night when the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler had taken control of the Reichstag. A man now on a crusade against the new totalitarianism taking root in Germany, Halton pulled no punches. ‘Strutting up the Chancellery steps is Hitler, the cruel and cunning megalomaniac who owes his triumph to his dynamic diabolism and his knowledge of the brutal corners of the human soul’ he wrote in his memoir, Ten Years To Alamein in 1944, using language that made many in the West consider the journalist one of those alarmists who naïvely saw the world through a simplistic, sensationalist and self-righteous lens:

Surrounding him is his camarilla of braves: the murderous fat Goering, a vain but able man; the satanic devil’s advocate, Goebbels; the cold and inhuman executioner, Himmler; the robustious radical, Roehm, organizer of the Brown Shirts… Their supporters were decreasing in numbers; but by intrigue and a trick, Germany is theirs. Supporting this terrible elite are the brown-shirted malcontents of the S.A., nearly a million of them, and the black-uniformed bullies of the S.S., the praetorian guard. And the whole structure is built on the base of a nation whose people are easily moved by romantic imperialism, by the old pan-Germanism, in new and more dynamic form, by dreams of Weltmacht and desire for revenge, and even by nostalgia for the jungle and for the tom-toms of the tribe.

Halton, the Toronto Star’s London-based Europe reporter, was to prove one of the most prescient journalists of the age. The language he had begun to utilize when describing what he was seeing around him during his visits to German was urgent, prophetic, full of warning for what would happen to Europe, and the world, if it ignored what was happening, at great speed, to Germany. Laying aside journalistic convention, Halton became one of a tiny group of prophets who began urgently to warn the world of impending doom. ‘The things I saw being taught and believed everywhere in that nation’ he wrote in one of his reports from later in 1933, ‘the superiority of one race and its destiny to rule – will one day become the intimate concern of all of us.’

Halton was in no doubt what Hitler’s ascent to power meant for Germany. He visited twice that year, first in January and then, more extensively, in the fall. From the very first instant he suspected that the name Hitler had given to his political party – the National Socialist German Workers’ Party – was a merely an enormous, brazen hoax, designed for one end, and one end alone: an aggrandizing, racist agenda that would attempt to place Germany ahead of every other country of Europe, with force if necessary. From what he could see Hitlerism was neither National or Socialist, nor for that matter about the Workers. It seemed to him to be about the creation of a racially-pure Germany (in which Jews, gypsies and Slavs were obvious disposable imperfections), disciplined, obedient, militaristic, and imperial. Most worryingly of all was that the fabulous lie inherent in the banality of the name of this political party was widely believed, and constituted the basis of Hitler’s ascent to tyranny. To the fanatical few, the believers, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party was a means to an end, the first step of which was the assumption of total, dictatorial power, after which the principal themes of the February 24, 1920, Declaration – racial purification from within and territorial aggrandizement outside to form a Grosse Deutschland of 80 million Germans, in which Lebensraum was to be achieved – would be acted out, with legal violence if necessary. The name therefore fooled lots of Germans, as well as much of the watching world, few of whom ever bothered to read (or knew where to look) the defining articles of Nazi faith. The lie was carefully concealed within other myths of Germanhood, ones that enjoyed a widespread appeal, particularly among a people humiliated by defeat in 1918, confused by the political uncertainties of the Weimar years and pauperized by the collapse of Wall Street in 1929. It was the latter, much more than the impact of 1918, that lit the path for Germans, and Germany, down the road to the gates of a Nazi Valhalla. With a shock Halton understood that the Nazi creed was not being foisted unwillingly upon a reluctant population. Many in Germany welcomed the Nazis with open arms. ‘Germany enters a nightmare’ Halton wrote. ‘I feel it in my bones. She has heard the call of the wild.’

In the comfort of his English home, H.G. Wells dismissed the Nazi coup d’état that placed Hitler on the Chancellor’s chair as a ‘revolt of the clumsy lout’, a charge that led to the Nazi burning of his books – among thousands of others – in Berlin’s Opernplatz on May 10, 1933. Wells underestimated both the simplicity of the Nazi program, the ferocious tenacity of its adherents, and the unchallenging acquiescence of the mass of the population. His accusation proved to be naively off-hand, akin to the view amongst the aristocracy in the Heer that they could control the ‘little Corporal’. Wells gave no thought to the consequences the rise to power of the lout he described would have for Germany, or the world for that matter. This was no schoolyard bullying that would disappear with the maturity of age. That Hitlerism was ever able to so dominate European – and global – politics to the extent that it did for twelve hellish years – sending the world screeching into a cataclysmic war from which it only escaped by the skin of its teeth, battered, bloodied and changed forever – is no mystery now. In the early 1930s, however, the fast-approaching catastrophe wasn’t so obvious to everyone. Even though Europe was awash with North American journalists reporting back fearfully about the developments in the heart of Europe where the Enlightenment legacy of centuries, before which lay the Reformation and before that the Renaissance, was being buried by a darkness so unfathomable as to be unimaginable, few read the warning signs correctly. That the warning bells were ringing, loudly, in every country of Europe and indeed across the world is indisputable; what seems so shocking is that few bothered to lift their heads to listen.

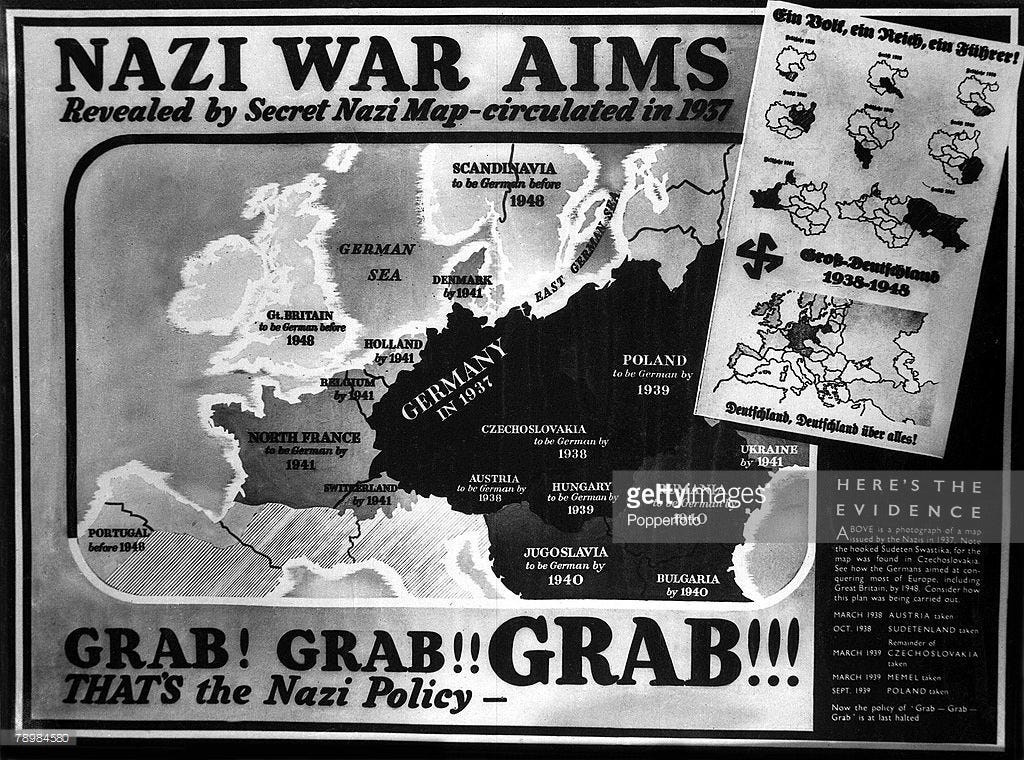

One of those who noisily rang the alarm bells, and who was roundly ignored, was the New York Herald Tribune journalist Leland Stowe, whose fears were succinctly articulated in a small book published in London in December 1933 with the uncompromising title, Nazi Germany Means War. Stowe, who had received a Pulitzer Prize in 1930 for his reporting of Great War reparations, was as shocked as Halton after he had spent two months in Germany that year. He concluded that Germany had two voices. One was a public voice meant to pacify the fears of outsiders, and spoke repeatedly of peace. The other was for internal, German, consumption, and spoke relentlessly of martial values, social discipline, the needs of the state eclipsing those of the individual, Germany’s requirement for living space, self-evident German racial superiority amongst the nations of Europe and of the imperative to achieve a homeland for all Germans, not just those who currently had the good fortune to live within the present boundaries of the Reich. What this meant for Austria, and for large slices of Poland and Czechoslovakia were clear to the Nazi propagandists, and a message preached diligently and persistently every day. These ends would be achieved, Hitler asserted in Mein Kampf, ‘by a strong and smiting sword.’ ‘Hitler declares that Nazi Germany wants peace at the very moment when Nazi Germany is busy, with an appalling systemization and efficiency, preparing its 65,000,000 people for perfected martial co-ordination such as has never existed before’ Stowe warned. ‘This, in its logical sequence, can finally lead only to war.’

Stowe’s book flopped. Neither buying public nor politician wanted to spend money on a tome that suggested that on its current course war was inevitable, and confirmed that their persistent ‘ostrichitis’ was a terminal illness. Equally, Halton’s reporting of his two-month tour of Germany in the autumn of 1933 for the Toronto Star was regarded to be so alarmist that he was dismissed by many as an exaggerator, a war-monger. He was criticized for reading into situations and events a meaning far beyond their reality. For suggesting that the Nazis and their followers were not Christians for instance – truly following the sayings and precepts of Christ – he incurred the wrath of Catholics and Protestants alike who accused him of ignorance. Germany was, after all, the most observant country in Europe. It was factually erroneous, the argument went, to suggest otherwise. The dominant theological world view across western Christendom in the 1930s was pacifism, which although it attempted to express in political terms Christ’s blessings on the peacemakers, and the instruction to ‘turn the other cheek’, seemed to assume that simply believing in non-violence would somehow persuade an enemy to think twice about using violence at all.

Halton, and others like him, were accused by Germans of not understanding the country, nor of the German hunger for a new political settlement and an honorable place in the world. It was a common enough accusation. Although Halton robustly dismissed the Western reactions to his warnings he nevertheless worried at the time that well-meaning ignorance of Nazism abroad was almost as bad as Nazism itself. If people only knew what hatreds lay at the heart of the Nazi creed, he thought, they would oppose it just as strongly as if they were fighting a burglar in their house. But because Nazism was cloaked in a cunning disguise, few people could see it for what it was.

Indeed, he believed that the fox was already inside the chicken-coop. The German people, or at least large numbers of them, had embraced ideas they would have regarded, in another political or cultural milieu, as desperately irrational. Vast swathes of Germany now espoused nonsensical racial views about their own superiority over other varieties of humankind that had no place in rational or scientific thought and which, as Halton observed, ‘one would have expected children to laugh at.’ What had happened to the most intellectual country in Europe? He concluded despondently that it seemed apparent ‘that the Germans were the least intelligent, if the most intellectual, of Western peoples.’ Using the same analogy, they were also the most religious, if unchristian. Shockingly, the crazy notions of Aryan supremacy propagated so assiduously by the Nazis had already received academic and intellectual legitimacy, and had been translated into notions that had quickly become widely accepted by otherwise thinking people, taught in schools and subsumed into common, everyday thought. He noted the prolifically published arguments of men such as the geographer, Professor Ewald Banse, whose ‘Military Science’ published in 1934 argued among other things that:

War is both inevitable and necessary, and therefore it is imperative, and the nation’s mind must be directed towards it from childhood. Children must learn to infect the enemies’ drinking water with typhoid bacilli and to spread plague with infected rats. They must learn military tactics from the birds, hills and streams.

How was it possible for the most cultured society in the world to embrace such extremism? Why – and how – could otherwise deeply intelligent, well-educated, rational men and women embrace such nonsense? Halton observed the transformation of the German mind at first hand. The recipe was simple. If one lived within a lie for long enough, it didn’t take long to fail to distinguish the lie from the truth. Ultimately, the power of the lie would trump reason, and the exercise of rational thought. Indeed, one began to believe the lie. In 1930 he had made several friends in Germany during visits when a student at the University of London. His new acquaintances were all socialists and internationalists, and laughed at the Nazi buffoons clowning around on the outskirts of politics. Three years later, after Hitler’s rise to power, he went to meet one of these men, living with his parents in the Rhineland town of Bonn. Halton was relieved to learn that this man had not supped from the Nazi cup, but was disquieted to hear that two of the others had become Nazis. Five years later, he returned to the family home during the Bad Godesberg conference in September 1938. “What a pity you should have come up from Godesberg” the man’s mother exclaimed when she saw Halton at the door, “because Friedrich is there! He commands a detachment of the S.A. which was sent from here to the conference.” All that was required was time, and the repeated articulation of the lie.

Leland Stowe’s experience of living in Germany in 1933 shocked him with how diametrically different it was to ordinary life in France, Britain or the United States. In Germany, for instance, uniforms abounded. A packet of cigarettes he purchased in a café included a gift of a picture of a soldier sitting behind a machine-gun. In restaurants, the music was a mixture of popular airs, and occasional waltz and the obligatory quota of Nazi marches:

I saw more uniformed men on the streets and in the public places of Berlin than I had seen in any foreign city from London to Constantinople. I witnessed more parades and marching troops in three weeks than I had seen in Paris in nine months. I heard rousing military bands at eleven o’clock in the morning, going by the office window, or on Hermann Goeringstrasse at eleven o’clock at night. I saw long columns of boys and girls in their teens, uniformed and carrying flags and marching somewhere at all sorts of unexpected hours. Often they sang and their voices were clear and high and in striking unison. I saw great swastika or imperial flags hung out everywhere; thousands of them, outdoors and indoors – always flags.

Three years later, when the 22-year-old Rhodes Scholar, Howard Smith arrived in Germany through the port of Bremen, he was overwhelmed by the militarization of society:

It took my breath away. I had read about Nazi rearmament, but to me it was still a word, not a sense-idea. In New Orleans, I could sum up in a figure of two integers all the uniforms I had ever seen. Before our boat docked in Bremen I saw a big multiple of that figure, sailors of Germany’s war navy, walking up and down the long wharves. The railway station in Bremen, and later every railway station I saw, was a milling hive of soldiers in green uniforms in full war-kit and with rifles, getting off trains and getting on them. Farther inland, towns looked like garrisons, with every third or fourth man in uniform. On trains, all day long, one passed long railway caravans of camouflaged tanks, cannon and war-trucks lashed to railway flat cars, and freight depots were lined with more of these monsters hooded in brown canvas. In large towns, traffic had to be interrupted at intervals on some days to let cavalcades of unearthly machines, manned by dust-covered, steel-helmeted Men-from-Mars roar through the main streets on maneuvers.

In 1933 Stowe commented on the catchy little musical ditty played during intermissions in radio programs, which proved to be the popular song Volk ans Gewehr (People, to Arms!). On the streets, young boys dressed in Hitler Youth uniforms and played with wooden cannons in the parks and practiced throwing hand-grenades as part of their school curriculum. At the time Halton, among many others, was concerned about the vast gulf that existed between what the Nazis said they were doing, and the interpretation of these things by newspapers, politicians and observers in other, far distant places, especially those safely cushioned in the protective cocoon of western, liberal democracy, who thought that all systems of government operated similarly, and where bad people were constrained by the law and the structures and systems of civilization. But it wasn’t only wishful-thinking Western intellectuals and politicians who harbored delusions about the Nazi program in Europe. In a 1933 interview with Goering, Halton was struck by how deeply the Nazi leadership had itself drunk from the cup of its own delusions. What was worse than believing their ridiculous racial bigotries, especially against the Jews within and the Untermenschen without, was their unfounded conviction that the policy-makers in the West secretly supported them, even if they couldn’t express this support openly. After all, it wasn’t a secret that it was western capital – sourced through London and Wall Street – that was financing the rebuilding of Germany, and which by necessity was close to the Nazi economic program. The interests of both sides were therefore closely aligned. If the outcome of Versailles was to be reversed, Goering asserted, Britain and France would be sensible. Both countries knew that Germany was Europe’s bulwark against the specter of Soviet bolshevism. ‘Germany will save Europe and occidental civilization’ he blathered. ‘Germany will stop the rot. Germany will prevent the Untergang des Abendlandes’. Goering was well-briefed about attitudes in the West. The well-read man or woman on the street in London and New York was already saying, and believing, some of this. Those in Warsaw, Prague and Paris were less inclined to do so, however. The unbelievers were widely ridiculed in their own countries. In Britain, Winston Churchill was the most prominent of those who did not accept this world-view, but for the most part the political establishment ignored and reviled him in equal measure. Churchill was, at the time, like a biblical prophet crying out in the wilderness, scoffed at by those who considered him a war-monger for advocating robust responses to the militaristic posturing of the totalitarian states.

Yet all it needed, argued Halton, was for people – in Germany and the West – to read. The Twenty-Five Demands of the 1924 Declaration were unequivocal. They were the Articles of Faith of a new religion, and held to fanatically by true believers. This was the foundation stone upon which all else was being built. Hitler had mapped out these plans for rebuilding Germany in this image in Mein Kampf, but had wisely refused his publishers permission to have the rambling tome translated into English. It would have given the game away. When Halton interviewed Albert Einstein at a secret location on England’s south coast in September 1933, he asked the famous scientist whether it was Hitler’s plan to destroy European Jewry. ‘Jewry?’ Einstein retorted. ‘Jewry has less to fear than Christendom. Can’t you people read?’ When Halton asked him what the ultimate result of the Nazi project would be, Einstein immediately responded “War. Can’t the whole world see that Hitler will almost certainly drag it into war...[?]” They couldn’t. Most Western diplomats and statesman in 1930s Europe made the mistake of misunderstanding Hitler’s true nature, and ambitions. After all, these – articulated in Mein Kampf, in repeated public utterances in Germany, in speeches and interviews – were so fantastical, outrageous even, that most reasonable men and women did not consider them viable, and so dismissed them utterly. This was the underlying reality of appeasement: sane politicians and statesmen believed that Hitler likewise was rationally calculating what he could secure by beating the war-drum, but without taking his country and people into a ruinous war. When they visited Hitler in person, the German Führer mollified them with honeyed lips. He was a man, the representatives of the democracies believed, with whom they could do business. Did he not repeatedly assert that he wanted peace? The appeasers did not realize – until it was too late – that if Hitler could not secure peace on his own terms, he would do so by means of war.

Halton visited Dachau in the late summer of 1933, at a time when carefully escorted visitors were still allowed, and came away – even in these early days of the Nazi Concentration Camps, before they had become mass killing machines – shocked not so much at the casual brutality of the place, as the political and social environment that sent people there in the first place. The inmates needed social re-education the guards explained, and training them to learn social discipline and civic obedience was an essential part of the program. The prisoners had only themselves to blame: if they had not demonstrated by their dalliance with communism, or Seventh Day Adventism or whatever their personal weakness had been, that they had behaved in a socially irresponsible way, they would not have to be punished. Brutalism was the new creed. The following year Dorothy Thompson, who had been reporting from Berlin on and off since 1925, recorded for Harper’s Magazine the sight of what appeared to be a delightful Hitler Youth summer camp at Murnau. On first arrival, she was much taken by the sight and sound of 6,000 adolescent voices singing in unison. Then she saw, on the hillside above the camp, in stark, black letters, a banner proclaiming ominously YOU WERE BORN TO DIE FOR GERMANY. Self-sacrifice on behalf of the state was a lifelong expectation. A brutal life would precede a brutal death, all in the name of Greater Germany. She found herself driving away from the place at the unprecedented speed of sixty-five miles an hour, so desperate was she to put it behind her. The Reverend Stewart Herman of the American Church in Berlin listened every Sunday morning in 1936 as the bells of all the surrounding steeples rang out at church time:

And almost every Sunday morning when the bells were inviting people to service I would hear the sound of tramping feet and singing voices marching down the converging streets into the near-by square. When I went to the window, as I often did, to see what was going on, the same scene always met my eyes. Columns of boys in brown shirts and dark-blue shorts – ski pants in winter – with heavy boots on their feet were parading along under banners and flags. They marched three abreast just like the regular infantry and they tried to take long steps like the soldiers they wished to imitate.

They were not marching to church, as they frequently used to do before Hitler came to power. These were the Hitler boys and they were going into the movie theatre just across the street to practise singing their songs of hatred and war and to be exhorted once more that to live and die for Germany – the greatest nation on earth – is the noblest aim in life. Other nations, they were informed, were trying to destroy the Fatherland but the Fuehrer had rescued the country just in the nick of time.

If the Germans accepted brutality amongst themselves, Halton observed, it would be easy, when the time came, to accept it as necessary for others. ‘Loutish brutality was being coldly cultivated as an instrument of national policy’ he concluded. The behaviour of many otherwise sane, intelligent Germans towards their enemies during the war that was to come had its roots deep in the common acceptance of such ideas long before hostilities were ever declared and German men donned their Hugo Boss-designed black or grey-green uniforms and goose-stepped to war.

Brutalism extended to the deliberate trampling of other social sensitivities and age-old cultural and religious proscriptions. On one occasion during the tour Halton and his wife visited a camp at Vaterstetten a few miles east of Munich, housing young women being groomed to be ‘brides of Hitler.’ Their duty was to couple with carefully selected local soldiers – tall, strong, fair-haired and blue-eyed specimens of racial superiority – to produce sound Aryan stock with which to populate the lands that Grosse Deutschland would one day encompass. The young women they interviewed believed this mission, passionately. Here was the evidence that the Nazi plan, even in its infancy, was acting out the Program first agreed in 1920. The inevitable consequence of Lebensraum was the subjugation of the Untermenschen who already lived in these territories, and their repopulation by true, racially pure, German stock. No stigma was attached to their production of children out of wedlock. Indeed, the regime encouraged and applauded their efforts. ‘The body of the German girl must be steeled and hardened like that of the German man’ recited one young woman they interviewed. ‘Only the sound health of millions of German women can guarantee the vitality of the German people and the historical greatness of the German race.’ The idea of the Hitler-bride, Halton recorded, was ‘to become as rarefied and mystic as anything in theology.’ Piece by piece the old Germany was being destroyed, and reshaped into a different, more terrifying, image.

Stewart Herman was later to equate the encouragement of Aryan procreation with the careful and deliberate slaughter of the old and the mentally and physically infirm:

In August, 1940, a German pastor, boiling with helpless indignation, told me that the Gestapo planned to disembarrass the nation of three-quarters of a million mental and physical invalids who were eating German food and absorbing the energies of healthy German doctors, nurses, and guardians. Some next-of-kin were the startled recipients of notifications that their relatives had “died” shortly after being transferred, without warning, to one or the other of three institutions which quickly became notorious. Other next-of-kin were frantically trying to withdraw their relatives from public hospitals and homes.

The destruction of these ‘useless mouths’ helpfully provided ‘extra space for the additional tens of thousands of babies which German mothers were to be prevailed upon to bear.’

A year after Halton’s tour of Germany the journalist William (‘Bill’) Shirer and his wife Theresa (‘Tess’) Stiberitz, an Austrian photographer, returned to Berlin after an absence of several years, in the employ of William Randolph Hearst’s Universal Service. Shirer was profoundly shocked by what he found, and staggered around for the first few days in a fog of depression. Where was the old Berlin he had known, and loved only a few years back? The stimulating conversations of yore in the ‘care-free, emancipated, civilized air’ of an age now lost to history, where ‘snub-nosed young women with short-bobbed hair and the young men with either cropped or long hair – it made no difference – who sat up all night with you and discussed anything with intelligence and passion’ had been replaced by the depressing paraphernalia of a police state. It was now September 1934. Uniforms were everywhere. Heels clicked. Blood-red Swastika flags adorned windows and lamp posts. Posters depicted steel-jawed soldiers defending the Fatherland, or rapine Jews rubbing their hands over ill-gotten (German) booty. Troops marched. A favorite song was Siegreich Wollen Wir Frankreich Schlagen – “Victoriously We Must Smash France.” The ubiquitous Heil Hitler grated. It was increasingly dangerous not to acknowledge – using the Nazi’s preposterous raised arm salute – marching troops and banners on the street. Likewise, the journalist Janet Flanner watched this new cultural norm spread across Germany like an ink-blot.

[The phrase] with the Roman arm salute (originally a password among his militia), soon became the social greeting de rigueur among Germany’s civilians, and was officially called ‘the German greeting’ in distinction to the old Bürgerliche Gruss, or bourgeois Guten Tag. In Bavaria, where the greeting used to be ‘Grüss Gott’ Hitler’s name has been substituted for that of God. As most German aristocrats still click their heels, kiss the ladies’ hands, and, if in uniform, add the old-fashioned military salute, these, plus the Nazi arm-flinging, make modern German salutations fairly acrobatic affairs.

Shirer found himself ducking into shops just to avoid these increasingly frequent occurrences. He gritted his teeth. He had a feeling that things were going to get much worse before they got better. Two days later, following the long train ride south to Nuremberg, he recorded his first ever Nazi Party parade. It was only the fourth of its kind in history, and yet this party of gangsters now ran Germany. Where would they take it? Would the German people allow it, or would sense and rationality return after the nightmare? He watched Hitler ride into the ancient town like a Roman emperor ‘past solid phalanxes of wildly cheering Nazis who packed the narrow streets’, but was surprised at the dullness of the man. Dressed in a worn gabardine trench-coat, Hitler did not present an imposing figure. He had none of the self-conscious grandiloquence of Mussolini, fumbled with his cap and stared blankly at ‘his Germans’ as he liked to call them as the crowds cheered in ecstatic adulation. It was all rather confusing. The man who had transformed the political dynamic in Germany so dramatically, and was a demi-god to many, appeared to have none of the personal charisma that Shirer expected to be a prerequisite for such a figure. ‘He almost seemed to be affecting a modesty in his bearing’ he was forced to conclude. ‘I doubt if it’s genuine.’ Yet that night he watched as a ‘mob of ten thousand hysterics… jammed the moat in front of Hitler’s hotel, shouting: “We want our Führer.”

The young Howard Smith was equally confused. He caught sight of Hitler close up at the opera in Munich in 1937, and observed that the spectacle was impressive because Hitler was not:

He was a short, very short, little, comical looking man. Had his eyes had the firm, warm glow of Lincoln’s or the dash of Kaiser Wilhelm’s, it would have been different, but his eyes were beady little black dots with timid circles under them. Had his moustache the boldly turned up ends like that of Hindenburg, it would have been otherwise. But his was a laughable little wisp of hair not as broad as his crooked mouth or the under-part of his nose. That was what, after you smothered your first unconscious smile, alarmed you, and brought back in its fullest strength the haunting fear of the Myth. This was the thing that had built a party in impossible circumstances, taken over control of a nation and created the mightiest army in the world. This, the “apotheosis of the little man,” was what I saw as the blood-spitting, fire-breathing monster of the future. This funny little figure with its crooked smile, flapping its hand over its black-coated shoulder in salute, was God the omnipotent and infinite, Siegfried the hero of Nordics, and Adolf Hitler, the coming ruler of a destroyed world.

Shirer thought that the behaviour of these frantic disciples reminded him of religious enthusiasts he had once met in the Louisiana backwoods. They certainly considered Hitler to be their messiah. The outstretched arms of thousands of devotees reached to the sky. It was thus in flash of understanding that Shirer understood the truth. Nazism was, of course, a religious creed as powerful as any in history. Hitler was the God of this faith. Dorothy Thompson likewise saw this in 1934 when she was expelled from Germany, remarking, ‘As far as I can see, I was really put out of Germany for the crime of blasphemy. My offense was to think that Hitler was just an ordinary man, after all. That is a crime in the reigning cult in Germany, which says Mr. Hitler is a Messiah sent by God to save the German people – an old Jewish idea. To question this mystic mission is so heinous that, if you are a German, you can be sent to jail.’ Hitler did not force Christianity to kneel at the altar of National Socialism. With a few exceptions it did so willingly, understanding only too clearly that the German people now had a choice of religions, and that Hitler was as attractive as anything the liberal German Church could offer. Here was gorgeous pomp; glorious ritual; dramatic heraldry fluttering over the medieval streets; bands playing Hitler’s own Badenweiler Marsch with its resonating cymbals and heavy drum beat, and the magical feast of black uniforms (designed by Party member Hugo Boss), shining swords and polished helmets. It was a martial heaven, as the Nazis always intended it to be. Unbelievably, the spectacle went on for a week. By the end Shirer was exhausted, physically, mentally and emotionally. But he now realized the hold that Hitler had ‘on the people, to feel the dynamic in the movement he’s unleashed and the sheer, disciplined strength the Germans’ possess.’

The relentless diet of propaganda inside the borders of the Reich was accompanied by the strangulation of unbiased news from abroad. In an age before mass travel, few knew anything how what was happening outside of their country other than what they were told. Only the friendliest of foreign newspapers were allowed to circulate freely in Germany, one of which was London’s Times, which Shirer observed to have an immense circulation in January 1936. As time went on, however, the State attempted to secure a monopoly of news, and listening to foreign radio stations, the most popular being the German language programmes of the B.B.C., Radio America, Radio Moscow and the Swiss Beromünster, rapidly became criminal offences.

On May 21, 1935 Shirer recorded in his diary that Hitler had made yet another masterful speech in the Reichstag proclaiming his desire for peace. Yet, like Halton, Stowe and Thompson among others, Shirer saw clearly through the noisy charade. Hitler was in fact calling for war, under the cloak of demands for concord. It was the assassin’s knife: hidden until it was plunged, deep and red, into the body politic of Germany’s enemies. Shirer was now convinced of Hitler’s remarkable powers of oratory: what he lacked in visual presentation he made up for in his fantastical speeches. He held his audiences spellbound, but the demands he made that night in exchange for peace revealed that in fact they were impossible for Europe to accept. And what did he get for this drum-banging? Fear. In Western capitals politicians did not want to stand by the provisions of the treaties jointly made at Versailles in 1919 and Locarno in 1925, and were afraid to resist the demands for a reasoned, rational, adult conversation about Germany’s proper place in the world. After all, she was merely exerting her natural rights, the argument went, and Versailles was embarrassingly – and unnecessarily – harsh. We would do the same, surely, given similar circumstances. Give her some leeway. She is no threat to us. Using these arguments, at a stroke Great Britain allowed Germany at the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in London to break free of the Versailles straight-jacket, providing her with the ability to build as many submarines as the British. ‘Why the British have agreed to this is beyond me’ remarked Shirer, unpersuaded of the argument that embracing Germany would make her more peaceful. ‘German submarines almost beat them in the last war, and may in the next.’

At a speech to the Reichstag on March 8, 1936 Hitler revealed this inherent – through carefully hidden – contrast between his demand for peace and his desire for war. After a diatribe against the threat of bolshevism, Hitler told Germany – for the first time – that he was unilaterally rescinding the Versailles treaty with respect to the demilitarization of the Rhineland. At the same time, he repudiated the 1925 Treaty of Locarno. This was all in pursuit of peace, but one that was this time favorable to Germany and her interests. It mattered not whether these conflicted with those of her neighbors: only Germany mattered. Shirer found himself in the Reichstag watching Hitler’s performance, marveling at the consummate manner in which Hitler controlled his baying crowd, shouting out in synchronized union the ‘seig heil’ chant invented (so he claimed) by Hitler’s half-American foreign press chief, ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengl:

Now the six hundred deputies, personal appointees all of Hitler, little men with big bodies and bulging necks and cropped hair and pouched bellies and brown uniforms and heavy boots, little men of clay in his fine hands, leap to their feet like automatons, their right arms upstretched in the Nazi salute, and scream “Heil’s” the first two or three wildly, the next twenty-five in unison, like a college yelk Hitler raises his hand for silence. It comes slowly. Slowly the automatons sit down. Hitler now has them in his claws. He appears to sense it. He says in a deep, resonant voice: “Men of the German Reichstag!” The silence is utter.

Hitler then dropped the bombshell none were expecting:

In this historic hour, when in the Reich’s western provinces German troops are at this minute marching into their future peace-time garrisons, we all unite in two sacred vows.

He could go no further, Shirer recorded. The noise was deafening:

It is news to this hysterical “parliamentary” mob that German soldiers are already on the move into the Rhineland. All the militarism in their German blood surges to their heads. They spring, yelling and crying, to their feet… Their hands are raised in slavish salute, their faces now contorted with hysteria, their mouths wide open, shouting, shouting, their eyes, burning with fanaticism, glued on the new god, the Messiah. The Messiah plays his role superbly. His head lowered as if in all humbleness, he waits patiently for silence. Then, his voice still low, but choking with emotion, utters the two vows:

“First, we swear to yield to no force whatever in the restoration of the honor of our people, preferring to succumb with honor to the severest hardships rather than to capitulate. Secondly, we pledge that now, more than ever, we shall strive for an understanding between European peoples, especially for one with our western neighbor nations... We have no territorial demands to make in Europe! ...Germany will never break the peace.” It was a long time before the cheering stopped.

It wasn’t just the Reichstag that cheered Hitler. The repudiation of Versailles was endorsed by most Germans, even those who had no time for their country’s leader. Rhinelanders, who certainly didn’t want another war with France, as Shirer reported, had also caught ‘the Nazi bug’ and were hysterical about this supposed recovery of Germany’s sovereignty, self-respect and self-determination. The ‘Nazi bug’ had a particularly military air to it, as Howard Smith observed:

Every fiber and tissue of the social fabric was strained towards that single needle-point goal of war. Newspapers screamed belligerency and hate every single day. The objects of the belligerency altered with expediency, but the screaming tone was unvaried. ‘We have been wronged by A; we are being threatened by B; we will right those wrongs and eliminate that threat, and Heaven help any misguided individual who stands in our way!’ Children were taught it in schools; we were given a milder dose of it in the university. Soldiers had it drilled into them as another reflex. Art was nothing but war posters. Germany clearly and unequivocally wanted war and told the world so in tones so distinct that it was criminal to disbelieve them.

Peace! It was that simple. Hitler prefaced all his military actions with the claim that his ultimate purpose was peace. He was right, of course, except that this wasn’t what it seemed. Germany would accept peace after whatever war was necessary to reassert the rights due to it by its ancient birthright. Indeed, Hitler preached peace long and loudly. So much so that any accusation that he in fact wanted war sounded deliberately argumentative, even subversive. Yet Mein Kampf made it explicitly clear that Hitler saw war to be inevitable, and that peace was acceptable only on terms favorable to Hitler’s concept of Germany’s manifest destiny. Indeed, the one thing that the Nazi elite held to fanatically was the 25 demands of the ‘Program of the National Socialist German Workers Party’ signed on February 24, 1920, the first four being:

We demand the union of all Germans to form a Great Germany…

We demand equality of rights for the German People in its dealings with other nations, and abolition of the Peace Treaties of Versailles and St. Germain.

We demand land and territory (colonies) for the nourishment of our people and for settling our superfluous population.

None but members of the nation may be citizens of the State. None but those of German blood, whatever their creed, may be members of the nation. No Jew, therefore, may be a member of the nation.

Hitler’s claims of peace were therefore, as Halton described them, hollow, ‘pap for his own people – and ours – and is the most blatant mockery to anyone who sees Germany now.’ Yet on the streets of Berlin, London and New York, the wide-eyed and close-minded repeated the mantra that Hitler wanted peace, and was seeking merely self-respect for the Motherland. What country did not want this for itself? Why could the Versailles victors demand one thing for themselves and something completely different for their vanquished foe? For how long was Germany going to be punished for losing the Great War? Did not this violate every principle of natural justice?

Few American visitors to Germany in the mid-1930s failed to see that Germany itself was not at peace. As Dorothy Thompson reported during a visit in 1934, the traditional courtesy of Germans remained, but now it was façade for fear: of being watched, reported on and having to talk within the constraints of a new orthodoxy. There could be no criticism of Hitler, the National Socialists or their dream for a new Germany, nor indeed anything that might be construed as being anti-German. People could no longer speak freely; there was no freedom of the press; telephones were monitored; strikes were forbidden; dissenters disappeared, sometimes forever, into hidden jails run by the trench-coated Gestapo. Fear seemed to stalk the streets. People became careful about what they said, where and to whom. Josephine (Josie) Herbst returned to Berlin in 1936, where she had first lived in 1922, and saw through the façade of cleanliness, order and discipline:

For anyone who knew Germany in former years, it is a changed and sick country. Perhaps it is cleaner than before. The countryside is peculiarly orderly and beautiful… Yet silence is over the countryside, in little inns where one is sharply scrutinized, in trains, along streets. Talk does not bubble up anymore.

In a series of articles published in the New York Post in 1935 Herbst pulled no punches in her analysis of Nazi-run Germany. The daily abuse of the Jews, the omnipresent propaganda defining bolshevism as the greatest threat to the nation, and black-hearted Jews being the manufacturers of communist perfidy. In The Nation on January 8, 1936 she asked:

How long will the psychological reasons for submission to Hitler hold in the face of continuing economic instability for the great mass of people? Hitler has been successful in selling to the Germans the idea that he saved the country and all Europe from bolshevism, and that bolshevism is a destructive force, a strictly Jewish movement. Lately the term bolshevism with too much use has begun to lose its sharp edge. The Catholics also have been accused of bolshevism. The result has been to throw them into the opposition movement. In the Saar one of the illegal papers of the underground movement appears with the hammer and sickle combined with the Catholic cross. A priest about to be arrested was warned by the underground route; his house was surrounded by workers and peasants from the neighborhood, few of whom were Catholic, and the troopers coming to arrest him turned back at the sight of the dense crowd.

The existence of the underground movement is denied in the legal press, but twenty illegal papers come out regularly in Berlin alone. Hundreds of others appear irregularly. The papers are distributed by children and by workers during their working hours. The penalty for distributing such contraband may be the concentration camp; it may be death. Strikes are treason, and leaders are punished by death at the hands of a firing squad or by sentences to concentration camps. Yet strikes go on. Dozens occurred last summer, especially in the metal trades. Sometimes the strike consisted in a passive laying down of tools for an hour. Sometimes work was merely slowed up, ‘sticking,’ as they term it, ‘to the hands.’ Demonstrations used to be made for the release of [Ernst] Thälmann, the Communist leader, but lately there have been none, and it is not known for certain whether he is alive or dead. Only Germans who get their information from the legal press have any illusions about the so-called ‘bloodless revolution’ of the Nazis; blood has flowed and is flowing.

The shocking dissonance between the young men of his own age in Germany and his own upbringing in New Orleans startled the youthful Howard Smith when he visited Germany in 1936. Together with a friend they decided to cycle from Heidelberg to the ancient city of Worms on the west bank of the Rhine, following the re-occupation of the Rhineland, to see what they could see. It proved to be a revelation:

The town was not in war, yet, but it was the best imitation of a town-in-war I have ever seen. The streets were filled with soldiers. On every corner forests of new sign-posts told the way to parking grounds for motorized units, regimental headquarters, divisional headquarters, corps headquarters, field hospitals. We elbowed our way the length of the main street and saw not another man in civilian dress. That evening we spent in a beer-hall, in ‘whose upper stories we had rented rooms. The beer-hall was packed with fine-looking young officers, drinking, shouting, and singing. The tables were wet with spilled beer and the air hazy with blue cigarette smoke. I do not know what it was, except that the turn of this reaction was logically due – it was perhaps partly that the beer had loosened up my imagination – but watching the faces of these men, my own age, my own generation, caused me to think of their military culture, for the first time, in terms of me and my culture. For the first time I thought of Germany, not as an academic subject studiously to gather facts about for discussion at home, but as a real, direct and imminent threat to the existence of a civilization which gathers facts and discusses. A schism deeper than the Grand Canyon separated my world from that of the young man across from me, whose face bore fencing scars and carried a monocle over one glassy eye. The fetishes of my world, the values it worshipped, if it did not always attain them, were contained in words like “Reason,” “Think,” “Truth.” His fetishes and his values were “Feel,” “Obey,” “Fight.” There was no base pride for me in this involuntary comparison; rather, a terror like that which paralyses a child alone in the dark took hold of me. For, my world, with all the good qualities I thought it had, was, in terms of force, weak; his was mighty, powerful, reckless. It screamed defiance at my world from the housetops. One had to be deaf not to hear it.

By September 1937 the Shirer’s had decided to move their home to Vienna, Tess’s home city, and far – they thought – from the stultifying repression of Berlin. In his diary Shirer summed up his experience of the previous three years. The good things – the theatre (when it stuck to pre-Nazi plays); their many friends; the lakes, parks and woods around the city, ‘where you could romp and play and sail and swim, forgetting so much’ – was balanced by the horror of the Nazi regime, where ‘the shadow of Nazi fanaticism, sadism, persecution, regimentation, terror, brutality, suppression, militarism, and preparation for war has hung over all our lives, like a dark, brooding cloud that never clears.’

The world did not understand the real Germany. Wallace Deuel wrote in the Chicago Daily News in February 1941 that one ‘of the chief reasons why much of the outside world has failed to understand the Nazis and what they have been doing and are planning to do is that people simply cannot believe that the Nazis are the kind of men they are.’ This truth lay at the heart of appeasement, and accounts in major part for its failure. Well-meaning visitors wanted to believe that Hitler and his henchmen were merely healing Germany by restoring its self-respect after the horrors of humiliation and the subsequent worldwide financial crisis. They were also imposing discipline following chaos. Surely no one, not even Hitler, wanted war? Was that not self-evident from Hitler’s repeated speeches? It was ridiculous to assert that Hitler, now he was in power, would take Germany down the paths of the extremist nationalism he had espoused in his immature political youth. This view was superficial and naïve, Shirer considered, because it saw the extent of Nazi politics only through the dangerous self-limiting prism of western wishful thinking. Germany was, he believed, hard set on a path that would let it to inevitable conflict with all – states, groups and individuals – who opposed him, and the evidence was everywhere. Like a rabid dog, Hitler would keep on slathering and biting until he was destroyed. The ultimate end of Hitler’s plan for Germany, and the purpose of all his policies – Four Year Plans; ‘guns before butter’ speeches by the Nazi elite and every evidence of the obvious resurgence of the Reichswehr – was Total War, he thought: there was no other rational explanation. Despite the strictures of Versailles – none of which were being enforced by the International Community who had imposed them – every public parade saw new and better guns, faster tanks, more aircraft. Matthew Halton agreed. At the end of 1933 he had written in the Toronto Star: ‘During the last month in Germany I have studied the most fanatical, thoroughgoing and savage philosophy of war ever imposed on a nation. Unless I am deaf, dumb and blind, Germany is becoming a vast laboratory and breeding-ground for war... They are sowing the wind.’

But few at home paid him any attention. It wasn’t politically acceptable in the West to believe that war was the ultimate political ambition of Nazi philosophy, and of the new Nazi government. It was too preposterous for words. The failure of liberalism in the 1930s was the naivety to accept that any sane, rational human being wanted to be illiberal.

An excellent article on the rise of the Nazis in Germany. It reminded me of Professor Frank McDonough’s works, typically “Hitler and the Rise of the Nazi Party”. He has an interesting analysis of Chamberlain, his appeasement, and the British Road to War, published in 1998.

Robert, this post reminded me a lot of your book Victory to Defeat. They are different subjects, yes, but both deliver the same essential warning: complacency is dangerous. Whether it’s military institutions after WWI or democracies turning a blind eye to rising authoritarianism, the pattern is the same. Thanks for continuing to highlight these hard but necessary lessons.